This article was originally published Dec 31, 1999 by the Krisis Group.

1. The rule of dead labour

A corpse rules society – the corpse of labour. All powers around the globe formed an alliance to defend its rule: the Pope and the World Bank, Tony Blair and Jörg Haider, trade unions and entrepreneurs, German ecologists and French socialists. They don’t know but one slogan: jobs, jobs, jobs!

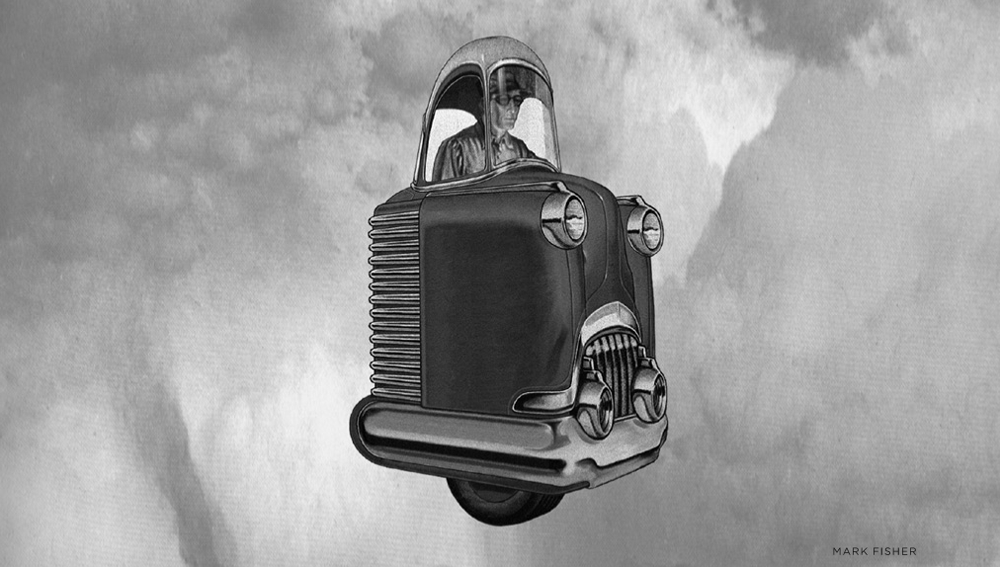

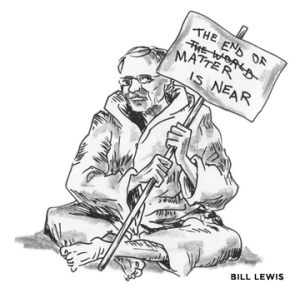

Whoever still has not forgotten what reflection is all about, will easily realise the implausibility of such an attitude. The society ruled by labour does not experience any temporary crisis; it encounters its absolute limit. In the wake of the micro-electronic revolution, wealth production increasingly became independent from the actual expenditure of human labour power to an extent quite recently only imaginable in science fiction. No one can seriously maintain any longer that this process can be halted or reversed. Selling the commodity labour power in the 21st century is as promising as the sale of stagecoaches has proved to be in the 20th century. However, whoever is not able to sell his or her labour power in this society is considered to be „superfluous“ and will be disposed of on the social waste dump.

Those who do not work (labour) shall not eat! This cynical principle is still in effect; all the more nowadays when it becomes hopelessly obsolete. It is really an absurdity: Never before the society was that much a labour society as it is now when labour itself is made superfluous. On its deathbed labour turns out to be a totalitarian power that does not tolerate any gods besides itself. Seeping through the pores of everyday life into the psyche, labour controls both thought and action. No expense or pain is spared to artificially prolong the lifespan of the „labour idol“. The paranoid cry for jobs justifies the devastation of natural resources on an intensified scale even if the destructive effect for humanity was realised a long time ago. The very last obstacles to the full commercialisation of any social relationship may be cleared away uncritically, if only there is a chance for a few miserable jobs to be created. „Any job is better than no job“ became a confession of faith, which is exacted from everybody nowadays.

The more it becomes obvious that the labour society is nearing its end, the more forcefully this realisation is being repressed in public awareness. The methods of repression may be different, but can be reduced to a common denominator. The globally evident fact that labour proves to be a self-destructive end-in-itself is stubbornly redefined into the individual or collective failure of individuals, companies, or even entire regions as if the world is under the control of a universal idée fixe. The objective structural barrier of labour has to appear as the subjective problem of those who were already ousted.

To some people unemployment is the result of exaggerated demands, low-performance or missing flexibility, to others unemployment is due to the incompetence, corruption, or greed of „their“ politicians or business executives, let alone the inclination of such „leaders“ to pursue policies of „treachery“. In the end all agree with Roman Herzog, the ex-president of Germany, who said that „all over the country everybody has to pull together“ as if the problem was about the motivation of, let us say, a football team or a political sect. Everybody shall keep his or her nose to the grindstone even if the grindstone got pulverised. The gloomy meta-message of such incentives cannot be misunderstood: Those who fail in finding favour in the eyes of the „labour idol“ have to take the blame, can be written off and pushed away.

Such a law on how and when to sacrifice humans is valid all over the world. One country after the other gets broken under the wheel of economic totalitarianism, thereby giving evidence for the one and only „truth“: The country has violated the so-called „laws of the market economy“. The logic of profitability will punish any country that does not adapt itself to the blind working of total competition unconditionally and without regard to the consequences. The great white hope of today is the business rubbish of tomorrow. The raging economical psychotics won’t get shaken in their bizarre worldview, though. Meanwhile, three quarters of the global population were more or less declared to be social litter. One capitalist centre after the other is dashed to pieces. After the breakdown of the developing countries and after the failure of the state capitalist squad of the global labour society, the East Asian model pupils of market economy have vanished into limbo. Even in Europe, social panic is spreading. However, the Don Quichotes in politics and management even more grimly continue to crusade in the name of the „labour idol“.

Everyone must be able to live from his work is the propounded principle. Hence that one can live is subject to a condition and there is no right where the qualification can not be fulfilled.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Foundations of Natural Law according to the Principles of Scientific Theory, 1797

2. The neo-liberal apartheid society

Should the successful sale of the commodity „labour power“ become the exception instead of the rule, a society devoted to the irrational abstraction of labour is inevitably doomed to develop a tendency for social apartheid. All factions of the comprehensive all-parties consensus on labour, so to say the labour-camp, on the quiet accepted this logic long ago and even took over a strictly supporting role. There is no controversy on whether ever increasing sections of the population shall be pushed to the margin and shall be excluded from social participation; there is only controversy on how this social selection is to be pushed through.

The neo-liberal faction trustfully leaves this dirty social-Darwinist business to the „invisible hand“ of the markets. This conception is utilised to justify the dismantling of the welfare state, ostracising those who can no longer keep abreast in the rat race of competition. Only those who belong to the smirking brotherhood of globalisation winners are awarded the quality of being a human. It goes without saying that the capitalist end-in-itself may claim any natural resources of the planet. When they can no longer be profitably mobilised, they have to lie fallow even if entire populations go hungry.

The police, salvation sects, the Mafia, and charity organisations become responsible for that annoying human litter. In the USA and most of the central European countries, more people are imprisoned than in any average military dictatorship. In Latin America, day after day an ever-larger number of street urchins and other poor are hunted down by free enterprise death-squads than dissidents were killed during the worst periods of political repression. There is only one social function left for the ostracised: to be the warning example. Their fate is meant to goad on those who still participate in the rat race of fighting for the leftovers. And even the losers have to be kept in hectic moving so that they don’t hit on the idea to of rebelling against the outrageous impositions they face.

Nevertheless, even at the price of self-annihilation, for most people the brave new world of the totalitarian market economy will only provide for a live in shadow as shadow-humans in a „shady“ economy. As low-wage-slaves and democratic serfs of the „service society, they will have to fawn on the well-off winners of globalisation. The modern „working poor“ may shine the shoes of the last businessmen of the dying labour society, may sell contaminated hamburgers to them, or may join the Security Corps to guard their shopping malls. Those who left behind their brain on the coat rack may dream of working their way up to the position of a service industry millionaire.

In Anglo-Saxon countries this horror scenario is reality meanwhile as it is in Third World countries and Eastern Europe; and Euroland is determined to catch up in rapid strides. The relevant financial papers make no secret of how they imagine the future of labour. The children in Third World countries who wash windscreens at polluted crossroads are depicted as the shining example of „entrepreneurial initiative“ and shall serve as a role model for the jobless in the respective local „service desert“. „The role model for the future is the individual as the entrepreneur of his own labour power, being provident and solely responsible for all his own life“ says the „Commission on future social questions of the free states of Bavaria and Saxony“. In addition: „There will be stronger demand for ordinary person-related services, if the services rendered become cheaper, i.e. if the „service provider“ will earn lower wages“. In a society of human „self-respect“, such a statement would trigger off social revolt. However, in a world of domesticated workhorses, it will only engender a helpless nod.

The crook has destroyed working and taken away the worker’s wage even so. Now he [the worker] shall labour without a wage while picturing to himself the blessing of success and profit in his prison cell. […] By means of forced labour he shall be trained to perform moral labour as a free personal act.

Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, Die deutsche Arbeit (The German Labour), 1861

3. The neo-welfare-apartheid-state

The anti-neoliberal faction of the socially all-embracing labour camp cannot bring itself to the liking of such a perspective. On the other hand, they are deeply convinced that a human being that has no job is not a human being at all. Nostalgically fixated on the postwar era of mass employment, they are bound to the idea of reviving the labour society. The state administration shall fix what the markets are incapable of. The purported normality of a labour society is to be simulated by means of job programmes, municipally organised compulsory labour for people on dole or welfare, subsidies, public debt, and other policies of this sort. This half-hearted rehash of a state-regulated labour camp has no chance at all, but remains to be the ideological point of departure for broad stratums of the population who are already on the brink of disaster. Doomed to fail, such steps put into practice are anything else but emancipatory.

The ideological transformation of „scarce labour“ (tight labour market) into a prime civil right necessarily excludes all foreigners. The social logic of selection then is not questioned, but redefined: The individual struggle for survival shall be defused by means of ethnic-nationalistic criteria. „Domestic treadmills only for native citizens“ is the outcry deep from the bottom of the people’s soul, who are suddenly able to combine motivated by their perverse lust for labour. Right-wing populism makes no secret of such sentiment. Its criticism of „rival society“ only amounts to ethnic cleansing within the shrinking zones of capitalist wealth.

Whereas the moderate nationalism of social democrats or Greens is set on treating the old-established immigrants like natives and can even imagine naturalising those people should they be able to prove themselves harmless and affable. Thereby the intensified exclusion of refugees from the Eastern and African world can be legitimised in a populist manner even better and without getting into a fuss. Of course, the whole operation is well obscured by talking nineteen to the dozen about humanity and civilisation. Manhunts for „illegal immigrants“ allegedly sneaking in domestic jobs shall not leave behind nasty bloodstains or burn marks on German soil. Rather it is the business of the border police, police forces in general, and the buffer states of „Schengenland“, which dispose of the problem lawfully and best of all far away from media coverage.

The state-run labour-simulation is violent and repressive by birth. It stands for the absolute will to maintain the rule of the „labour idol“ by all means; even after its decease. This labour-bureaucratic fanaticism will not grant peace to those who resorted to the very last hideouts of a welfare state already fallen into ruins, i.e. to the ousted, jobless, or non-competitive, let alone to those refusing to labour for good reasons. Welfare workers and employment agents will haul them before the official interrogation commissions, forcing them to kow-tow before the throne of the ruling corpse.

Usually the accused is given the benefit of doubt, but here the burden of proof is shifted. Should the ostracised not want to live on air and Christian charity for their further lives, they have to accept whatsoever dirty and slave work, or any other absurd „occupational therapy“ cooked up by job creation schemes, just to demonstrate their unconditional readiness for labour. Whether such job has rhyme or reason, not to mention any meaning, or is simply the realisation of pure absurdity, does not matter at all. The main point is that the jobless are kept moving to remind them incessantly of the one and only law governing their existence on earth.

In the old days people worked to earn money. Nowadays the government spares no expenses to simulate the labour-„paradise“ lost for some hundred thousand people by launching bizarre „job training schemes“ or setting up „training companies“ in order to make them fit for „regular“ jobs they will never get. Ever newer and sillier steps are taken to keep up the appearance that the idle running social treadmills can be kept in full swing to the end of time. The more absurd the social constraint of „labour“ becomes, the more brutally it is hammered into the peoples‘ head that they cannot even get a piece of bread for free.

In this respect „New Labour“ and its imitators all over the world concur with the neo-liberal scheme of social selection. In simulating jobs and holding out beguiling prospects of a wonderful future for the labour society, a firm moral legitimacy is created to crack down on the jobless and labour objectors more fiercely. At the same time compulsory labour, subsidised wages, and so-called „honorary citizen activity“ bring down labour cost, entailing a massively inflated low-wage sector and an increase in other lousy jobs of that sort.

The so-called activating workfare does even not spare persons who suffer from chronic disease or single mothers with little children. Recipients of social benefits are released from this administrative stranglehold only as soon as the nameplate is tied to their toe (i.e. in mortuary). The only reason for such state-obtrusiveness is to discourage as many people as possible from claiming benefits at all by displaying dreadful instruments of torture – any miserable job must appear comparatively pleasant.

Officially the paternalist state always only swings the whip out of love and with the intention of sternly training its children, denounced as „work-shy“, to be tough in the name of their better progress. In fact, the pedagogical measures only have the goal to drum the wards out. What else is the idea of conscripting unemployed people and forcing them to go to the fields to harvest asparagus (in Germany)? It is meant to push out the Polish seasonal workers, who accept slave wages only because the exchange rate turns the pittance they get into an acceptable income at home. Forced labourers are neither helped nor given any „vocational perspective“ with this measure. Even for the asparagus growers, the disgruntled academics and reluctant skilled workers, favoured to them as a present, are nothing but a nuisance. When, after a twelve-hour day, the foolish idea of setting up a hot-dog stand as an act of desperation suddenly appears in a more friendly light, the „aid to flexibility“ has its desired neo-British effect.

Any job is better than no job.

Bill Clinton, 1998

No job is as hard as no job.

A poster at the December 1998 rally, organised by initiatives for unemployed people

Citizen work should be rewarded, not paid. […] Whoever does honorary citizen work clears himself of the stigma of being unemployed and being a recipient of welfare benefits.

Ulrich Beck, The Soul of Democracy, 1997

4. Exaggeration and denial of the labour religion

The new fanaticism for labour with which this society reacts to the death of its idol is the logical continuation and final stage of a long history. Since the days of the Reformation, all the powers of Western modernisation have preached the sacredness of work. Over the last 150 years, all social theories and political schools were possessed by the idea of labour. Socialists and conservatives, democrats and fascists fought each other to the death, but despite all deadly hatred, they always paid homage to the labour idol together. „Push the idler aside“, is a line from the German lyrics of the international working (labouring) class anthem; „labour makes free“ it resounds eerily from the inscription above the gate in Auschwitz. The pluralist post-war democracies all the more swore by the everlasting dictatorship of labour. Even the constitution of the ultra-catholic state of Bavaria lectures its citizens in the Lutheran tradition: „Labour is the source of a people’s prosperity and is subject to the special protective custody of the state“. At the end of the 20th century, all ideological differences have vanished into thin air. What remains is the common ground of a merciless dogma: Labour is the natural destiny of human beings.

Today the reality of the labour society itself denies that dogma. The disciples of the labour religion have always preached that a human being, according to its supposed nature, is an „animal laborans“ (working creature/animal). Such an „animal“ actually only assumes the quality of being a human by subjecting matter to his will and in realising himself in his products, as once did Prometheus. The modern production process has always made a mockery of this myth of a world conqueror and a demigod, but might have had a real substratum in the era of inventor capitalists like Siemens or Edison and their skilled workforce. Meanwhile, however, such airs and graces became completely absurd.

Whoever asks about the content, meaning, and goal of his or her job, will go crazy or becomes a disruptive element in the social machinery designed to function as an end-in-itself. „Homo faber“, once full of conceit as to his craft and trade, a type of human who took seriously what he did in a parochial way, has become as old-fashioned as a mechanical typewriter. The treadmill has to run at all cost, and „that’s all there is to it“. Advertising departments and armies of entertainers, company psychologists, image advisors and drug dealers are responsible for creating meaning. Where there is continual babble about motivation and creativity, there is not a trace left of either of them – save self-deception. This is why talents such as autosuggestion, self-projection and competence simulation rank among the most important virtues of managers and skilled workers, media stars and accountants, teachers and parking lot guards.

The crisis of the labour society has completely ridiculed the claim that labour is an eternal necessity imposed on humanity by nature. For centuries it was preached that homage has to be paid to the labour idol just for the simple reason that needs can not be satisfied without humans sweating blood: To satisfy needs, that is the whole point of the human labour camp existence. If that were true, a critique of labour would be as rational as a critique of gravity. So how can a true „law of nature“ enter into a state of crisis or even disappear? The floor leaders of the society’s labour camp factions, from neo-liberal gluttons for caviar to labour unionist beer bellies, find themselves running out of arguments to prove the pseudo-nature of labour. Or how can they explain that three-quarters of humanity are sinking in misery and poverty only because the labour system no longer needs their labour?

It is not the curse of the Old Testament „In the sweat of your face you shall eat your bread“ that is to burden the ostracised any longer, but a new and inexorable condemnation: „You shall not eat because your sweat is superfluous and unmarketable“. That is supposed to be a law of nature? This condemnation is nothing but an irrational social principle, which assumes the appearance of a natural compulsion because it has destroyed or subjugated any other form of social relations over the past centuries and has declared itself to be absolute. It is the „natural law“ of a society that regards itself as very „rational“, but in truth only follows the instrumental rationality of its labour idol for whose „factual inevitabilities“ (Sachzwänge) it is ready to sacrifice the last remnant of its humanity.

Work, however base and mammonist, is always connected with nature. The desire to do work leads more and more to the truth and to the laws and prescriptions of nature, which are truths.

Thomas Carlyle, Working and not Despairing, 1843

5. Labour is a coercive social principle

Labour is in no way identical with humans transforming nature (matter) and interacting with each other. As long as mankind exist, they will build houses, produce clothing, food and many other things. They will raise children, write books, discuss, cultivate gardens, and make music and much more. This is banal and self-evident. However, the raising of human activity as such, the pure „expenditure of labour power“, to an abstract principle governing social relations without regard to its content and independent of the needs and will of the participants, is not self-evident.

In ancient agrarian societies, there were all sorts of domination and personal dependencies, but not a dictatorship of the abstraction labour. Activities in the transformation of nature and in social relations were in no way self-determined, but were hardly subject to an abstract „expenditure of labour power“. Rather, they were embedded in complex rules of religious prescriptions and in social and cultural traditions with mutual obligations. Every activity had its own time and scene; simply there was no abstract general form of activity.

It fell to the modern commodity producing system as an end-in-itself with its ceaseless transformation of human energy into money to bring about a separated sphere of so-called labour „alienated“ from all other social relations and abstracted from all content. It is a sphere demanding of its inmates unconditional surrender, life-to-rule, dependent robotic activity severed from any other social context, and obedience to an abstract „economic“ instrumental rationality beyond human needs. In this sphere detached from life, time ceases to be lived and experienced time; rather time becomes a mere raw material to be exploited optimally: „time is money“. Any second of life is charged to a time account, every trip to the loo is an offence, and every gossip is a crime against the production goal that has made itself independent. Where labour is going on, only abstract energy may be spent. Life takes place elsewhere – or nowhere, because labour beats the time round the clock. Even children are drilled to obey Newtonian time to become „effective“ members of the workforce in their future life. Leave of absence is granted merely to restore an individual’s „labour power“. When having a meal, celebrating or making love, the second hand is ticking at the back of one’s mind.

In the sphere of labour it does not matter what is being done, it is the act of doing itself that counts. Above all, labour is an end-in-itself especially in the respect that it is the raw material and substance of monetary capital yields – the limitless dynamic of capital as self-valorising value. Labour is nothing but the „liquid (motion) aggregate“ of this absurd end-in-itself. That’s why all products must be produced as commodities – and not for any practical reason. Only in commodity form products can „solidify“ the abstraction money, whose essence is the abstraction labour. Such is the mechanism of the alienated social treadmill holding captive modern humanity.

For this reason, it doesn’t matter what is being produced as well as what use is made of it – not to mention the indifference to social and environmental consequences. Whether houses are built or landmines are produced, whether books are printed or genetically modified tomatoes are grown, whether people fall sick as a result, whether the air gets polluted or „only“ good taste goes to the dogs – all this is irrelevant as long as, whatever it takes, commodities can be transformed into money and money into fresh labour. The fact that any commodity demands a concrete use, and should it be a destructive one, has no relevance for the economic rationality for which the product is nothing but a carrier of once expended labour, or „dead labour“.

The accumulation of „dead labour“, in other words „capital“, materialising in the money form is the only „meaning“ the modern commodity producing system knows about. What is „dead labour“? A metaphysical madness! Yes, but a metaphysics that has become concrete reality, a „reified“ madness that holds this society in its iron grip. In perpetual buying and selling, people don’t interact as self-reliant social beings, but only execute the presupposed end-in-itself as social automatons.

The worker (lit. labourer) feels to be himself outside work and feels outside himself when working. He is at home when he does not work. When he works, he is not at home. As a result, his work is forced labour, not voluntary labour. Forced labour is not the satisfaction of a need but only a means for satisfying needs outside labour. Its foreignness appears in that labour is avoided as a plague as soon as no physical or other force exists.

Karl Marx, Economic-Philosophical Manuscripts, 1844

6. Labour and capital are the two sides of the same coin

The political left has always eagerly venerated labour. It has stylised labour to be the true nature of a human being and mystified it into the supposed counter-principle of capital. Not labour was regarded as a scandal, but its exploitation by capital. As a result, the programme of all „working class parties“ was always the „liberation of labour“ and not „liberation from labour“. Yet the social opposition of capital and labour is only the opposition of different (albeit unequally powerful) interests within the capitalist end-in-itself. Class struggle was the form of battling out opposite interests on the common social ground and reference system of the commodity-producing system. It was germane to the inner dynamics of capital accumulation. Whether the struggle was for higher wages, civil rights, better working conditions or more jobs, the all-embracing social treadmill with its irrational principles was always its implied presupposition.

From the standpoint of labour, the qualitative content of production counts as little as it does from the standpoint of capital. The only point of interest is selling labour power at best price. The idea of determining aim and object of human activity by joint decision is beyond the imagination of the treadmill inmates. If the hope ever existed that such self-determination of social reproduction could be realised in the forms of the commodity-producing system, the „workforce“ has long forgotten about this illusion. Only „employment“ or „occupation“ is a matter of concern; the connotations of these terms speak volumes about the end-in-itself character of the whole arrangement and the state of mental immaturity of the participants comes to light.

What is being produced and to what end, and what might be the consequences neither matters to the seller of the commodity labour power nor to its buyer. The workers of nuclear power plants and chemical factories protest the loudest when their ticking time bombs are deactivated. The „employees“ of Volkswagen, Ford or Toyota are the most fanatical disciples of the automobile suicide programme, not merely because they are compelled to sell themselves for a living wage, but because they actually identify with their parochial existence. Sociologists, unionists, pastors and other „professional theologians“ of the „social question“ regard this as a proof for the ethical-moral value of labour. „Labour shapes personality“, they say. Yes, the personalities of zombies of the commodity production who can no longer imagine a life outside of their dearly loved treadmills, for which they drill themselves hard – day in, day out.

As the working class was hardly ever the antagonistic contradiction to capital or the historical subject of human emancipation, capitalists and managers hardly control society by means of the malevolence of some „subjective will of exploitation“. No ruling caste in history has led such a wretched life as a „bondman“ as the harassed managers of Microsoft, Daimler-Chrysler or Sony. Any medieval baron would have deeply despised these people. While he was devoted to leisure and squandered wealth orgiastically, the elite of the labour society does not allow itself any pause. Outside the treadmills, they don’t know anything else but to become childish. Leisure, delight in cognition, realisation and discovery, as well as sensual pleasures, are as foreign to them as to their human „resource“. They are only the slaves of the labour idol, mere functional executives of the irrational social end-in-itself.

The ruling idol knows how to enforce its „subjectless“ (Marx) will by means of the „silent (implied) compulsion“ of competition to which even the powerful must bow, especially if they manage hundreds of factories and shift billions across the globe. If they don’t „do business“, they will be scrapped as ruthlessly as the superfluous „labour force“. Kept in the leading strings of intransigent systemic constraints they become a public menace by this and not because of some conscious will to exploit others. Least of all, are they allowed to ask about the meaning and consequences of their restless action and can not afford emotions or compassion. Therefore they call it realism when they devastate the world, disfigure urban features, and only shrug their shoulders when their fellow beings are impoverished in the midst of affluence.

More and more labour has the good conscience on its side: The inclination for leisure is called „need of recovery“ and begins to feel ashamed of itself. „It is just for the sake of health“, they defend themselves when caught at a country outing. It could happen to be in the near future that succumbing to a „vita contemplativa“ (i.e. to go for a stroll together with friends to contemplate life) will lead to self-contempt and a guilty conscience.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Leisure and Idleness, 1882

7. Labour is patriarchal rule

It is not possible to subject every sphere of social life or all essential human activities to the rule of abstract (Newtonian) time, even if the intrinsic logic of labour, inclusive of the transformation of the latter into „money-substance“, insists on it. Consequently, alongside the „separated“ sphere of labour, so to say at the rear, the sphere of home life, family life, and intimacy came into being.

It is a sphere that conveys the idea of femininity and comprises the various activities of everyday life which can only rarely be transformed into monetary remuneration: from cleaning, cooking, child rearing, and the care for the elderly, to the „labour of love“ provided by the ideal housewife, who busies herself with „loving“ care for her exhausted breadwinner and refuels his emptiness with well measured doses of emotion. That is why the sphere of intimacy, which is nothing but the reverse side of the labour sphere, is idealised as the sanctuary of true life by bourgeois ideology, even if in reality it is most often a familiarity hell. In fact, it is not a sphere of better or true life, but a parochial and reduced form of existence, a mere mirror-inversion subject to the very same systemic constraints (i.e. labour). The sphere of intimacy is an offshoot of the labour sphere, cut off and in its own meanwhile, but bound to the overriding common reference system. Without the social sphere of „female labour“, the labour society would actually never have worked. The „female sphere“ is the implied precondition of the labour society and at the same time its specific result.

The same applies to the gender stereotypes being generalised in the course of the developing commodity-producing system. It was no accident that the image of the somewhat primitive, instinct-driven, irrational, and emotional woman solidified only along with the image of the civilised, rational and self-restrained male workaholic and became a mass prejudice finally. It was also no accident that the self-drill of the white man, who went into some sort of mental boot camp training to cope with the exacting demands of labour and its pertinent human resource management, coincided with a brutal witch-hunt that raged for some centuries.

The modern understanding and appropriation of the world by means of (natural) scientific thought, a way of thinking that was gaining ground then, was contaminated by the social end-in-itself and its gender attributes down to the roots. This way, the white man, in order to ensure his smooth functioning, subjected himself to a self-exorcism of all evil spirits, namely those frames of mind and emotional needs, which are considered to be dysfunctional in the realms of labour.

In the 20th century, especially in the post-war democracies of Fordism, women were increasingly recruited to the labour system, which only resulted in some specific female schizophrenic mind. On the one hand, the advance of women into the sphere of labour has not led to their liberation, but subjected them to very same drill procedures for the labour idol as already suffered by men. On the other hand, as the systemic structure of „segregation“ was left untouched, the separated sphere of „female labour“ continued to exist extrinsic to what is officially deemed to be „labour“. This way, women were subjected to a double-burden and exposed to conflicting social imperatives. Within the sphere of labour – until now – they are predominantly confined to the low-wage sector and subordinate jobs.

No system-conforming struggle for quota regulations or equal career chances will change anything. The miserable bourgeois vision of a „compatibility of career and family“ leaves completely untouched the separation of the spheres of the commodity-producing system and thereby preserves the structure of gender segregation. For the majority of women such an outlook on life is unbearable, a minority of fat cats, however, may utilise the social conditions to attain a winner position within the social apartheid system by delegating housework and child care to poorly paid (and „obviously“ feminine) domestic servants.

Due to the systemic constraints of the labour society and its total usurpation of the individual in particular – entailing his or her unconditional surrender to the systemic logic, and mobility and obedience to the capitalist time regime – in society as a whole, the sacred bourgeois sphere of so-called private life and „holy family“ is eroded and degraded more and more. The patriarchy is not abolished, but runs wild in the unacknowledged crisis of the labour society. As the commodity-producing system gradually collapses at present, women are made responsible for survival in any respect, while the „masculine“ world indulges in the prolongation of the categories of the labour society by means of simulation.

Mankind had to horribly mutilate itself to create its identical, functional, male self, and some of it has to be redone in everybody’s childhood

Max Horkheimer/Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment

8. Labour is the service of humans in bondage

The identity of labour and bondman existence can be shown factually and conceptually. Only a few centuries ago, people were quite aware of the connection between labour and social constraints. In most European languages, the term „labour“ originally referred only to the activities carried out by humans in bondage, i.e. bondmen, serfs, and slaves. In Germanic speaking areas, the word described the drudgery of an orphaned child fallen into serfdom. The Latin verb „laborare“ meant „staggering under a heavy burden“ and conveyed the suffering and toil of slaves. The Romance words „travail“, „trabajo“, etc., derive from the Latin „tripalium“, a kind of yoke used for the torture and punishment of slaves and other humans in bondage. A hint of that suffering is still discernible in the German idiom „to bend under the yoke of labour“.

Thus „labour“, according to its root, is not a synonym for self-determined human activity, but refers to an unfortunate social fate. It is the activity of those who have lost their freedom. The imposition of labour on all members of society is nothing but the generalisation of a life in bondage; and the modern worship of labour is merely the quasi-religious transfiguration of the actual social conditions.

For the individuals, however, it was possible to repress the conjunction between labour and bondage successfully and to internalise the social impositions because in the developing commodity-producing system, the generalisation of labour was accompanied by its reification: Most people are no longer under the thumb of a personal master. Human interdependence transformed into a social totality of abstract domination – discernible everywhere, but proving elusive. Where everyone has become a slave, everyone is simultaneously a master, that is to say a slaver of his own person and his very own slave driver and warder. All obey the opaque system idol, the „Big Brother“ of capital valorisation, who harnessed them to the „tripalium“.

9. The bloody history of labour

The history of the modern age is the history of the enforcement of labour, which brought devastation and horror to the planet in its trail. The imposition to waste the most of one’s lifetime under abstract systemic orders was not always as internalised as today. Rather, it took several centuries of brute force and violence on a large scale to literally torture people into the unconditional service of the labour idol.

It did not start with some „innocent“ market expansion meant to increase „the wealth“ of his or her majesty’s subjects, but with the insatiable hunger for money of the absolutist apparatus of state to finance the early modern military machinery. The development of urban merchant’s and financial capital beyond traditional trade relations only accelerated through this apparatus, which brought the whole society in a bureaucratic stranglehold for the first time in history. Only this way did money became a central social motive and the abstraction of labour a central social constraint without regard to actual needs.

Most people didn’t voluntarily go over to production for anonymous markets and thereby to a general cash economy, but were forced to do so because the absolutist hunger for money led to the levy of pecuniary and ever-increasing taxes, replacing traditional payment in kind. It was not that people had to „earn money“ for themselves, but for the militarised early modern firearm-state, its logistics, and its bureaucracy. This way the absurd end-in-itself of capital valorisation and thus of labour came into the world.

Only after a short time revenue became insufficient. The absolutist bureaucrats and finance capital administrators began to forcibly and directly organise people as the material of a „social machinery“ for the transformation of labour into money. The traditional way of life and existence of the population was vandalised as this population was earmarked to be the human material for the valorisation machine put on steam. Peasants and yeomen were driven from their fields by force of arms to clear space for sheep farming, which produced the raw material for the wool manufactories. Traditional rights like free hunting, fishing, and wood gathering in the forests were abolished. When the impoverished masses then marched through the land begging and stealing, they were locked up in workhouses and manufactories and abused with labour torture machines to beat the slave consciousness of a submissive serf into them. The floating rumour that people gave up their traditional life of their own accord to join the armies of labour on account of the beguiling prospects of labour society is a downright lie.

The gradual transformation of their subjects into material for the money-generating labour idol was not enough to satisfy the absolutist monster states. They extended their claim to other continents. Europe’s inner colonisation was accompanied by outer colonisation, first in the Americas, then in parts of Africa. Here the whip masters of labour finally cast aside all scruples. In an unprecedented crusade of looting, destruction and genocide, they assaulted the newly „discovered“ worlds – the victims overseas were not even considered to be human beings. However, the cannibalistic European powers of the dawning labour society defined the subjugated foreign cultures as „savages“ and cannibals.

This provided the justification to exterminate or enslave millions of them. Slavery in the colonial plantations and raw materials „industry“ – to an extent exceeding ancient slaveholding by far, was one of the founding crimes of the commodity-producing system. Here „extermination by means of labour“ was realised on a large scale for the first time. This was the second foundation crime of the labour society. The white man, already branded by the ravages of self-discipline, could compensate for his repressed self-hatred and inferiority complex by taking it out on the „savages“. Like „the woman“, indigenous people were deemed to be primitive halflings ranking in between animals and humans. It was Immanuel Kant’s keen conjecture that baboons could talk if they only wanted and didn’t speak because they feared being dragged off to labour.

Such grotesque reasoning casts a revealing light on the Enlightenment. The repressive labour ethos of the modern age, which in its original Protestant version relied on God’s grace and since the Enlightenment on „Natural Law“, was disguised as a „civilising mission“. Civilisation in this sense means the voluntary submission to labour; and labour is male, white and „Western“. The opposite, the non-human, amorphous, and uncivilised nature, is female, coloured and „exotic“, and thus to be kept in bondage. In a word, the „universality“ of the labour society is perfectly racist by its origin. The universal abstraction of labour can always only define itself by demarcating itself from everything that can’t be squared with its own categories.

The modern bourgeoisie, who ultimately inherited absolutism, is not a descendant of the peaceful merchants who once travelled the old trading routes. Rather it was the bunch of Condottieri, early modern mercenary gangs, poorhouse overseers, penitentiary wards, the whole lot of farmers general, slave drivers and other cut-throats of this sort, who prepared the social hotbed for modern „entrepeneurship“. The bourgeois revolutions of the 18th and 19th century had nothing to do with social emancipation. They only restructured the balance of power within the arising coercive system, separated the institutions of the labour society from the antiquated dynastic interests and pressed ahead with reification and depersonalization. It was the glorious French revolution that histrionically proclaimed compulsory labour, enacted a law on the „elimination of begging“ and arranged for new labour penitentiaries without delay.

This was the exact opposite of what was struggled for by rebellious social movements of a different character flaring up on the fringes of the bourgeois revolutions. Completely autonomous forms of resistance and disobedience existed long before, but the official historiography of the modern labour society cannot make sense of it. The producers of the old agrarian societies, who never put up with feudal rule completely, were simply not willing to come to terms with the prospect of forming the working class of a system extrinsic to their life. An uninterrupted chain of events, from the peasants‘ revolts of the 15th and 16th century, the Luddite uprisings in Britain, later on denounced as the revolt of backwards fools, to the Silesian weavers‘ rebellion in 1844, gives evidence for the embittered resistance against labour. Over the last centuries, the enforcement of the labour society and the sometimes open and sometimes latent civil war were one and the same.

The old agrarian societies were anything but heaven on earth. However, the majority experienced the enormous constraints of the dawning labour society as a change to the worse and a „time of despair“. Despite of the narrowness of their existence, people actually had something to lose. What appears to be the darkness and plague of the misrepresented Middle Ages to the erroneous awareness of the modern times is in reality the horror of the history of modern age. The working hours of a modern white-collar or factory „employee“ are longer than the annual or daily time spent on social reproduction by any pre-capitalist or non-capitalist civilisation inside or outside Europe. Such traditional production was not devoted to efficiency, but was characterised by a culture of leisure and relative „slowness“. Apart from natural disasters, those societies were able to provide for the basic material needs of their members, in fact even better than it has been the case for long periods of modern history or is the case in the horror slums of the present world crisis. Furthermore, domination couldn’t get that deep under the skin as in our thoroughly bureaucratised labour society.

This is why resistance against labour could only be smashed by military force. Even now, the ideologists of the labour society resort to cant to cover up that the civilisation of the pre-modern producers did not peacefully „evolve“ into a capitalist society, but was drowned in its own blood. The mellow labour democrats of today preferably shift the blame for all these atrocities onto the so-called „pre-democratic conditions“ of a past they have nothing to do with. They do not want to see that the terrorist history of the modern age is quite revealing as to nature of the contemporary labour society. The bureaucratic labour administration and state-run registration-mania and control freakery in industrial democracies has never been able to deny its absolutist and colonial origins. By means of ongoing reification to create an impersonal systemic context, the repressive human resource management, carried out in the name of the labour idol, has even intensified and meanwhile pervades all spheres of life. Due to today’s agony of labour, the iron bureaucratic grip can be felt as it was felt in the early days of the labour society. Labour administration turns out to be a coercive system that has always organised social apartheid and seeks in vain to banish the crisis by means of democratic state slavery. At the same time, the evil colonial spirit returns to the countries at the periphery of capitalist „wealth“, „national economies“ that are already ruined by the dozen. This time, the International Monetary Fund assumes the position of an „official receiver“ to bleed white the leftovers. After the decease of its idol, the labour society, still hoping for deliverance, falls back on the methods of its founding crimes, even though it is already beyond salvation.

The barbarian is lazy and differs from the scholar by musing apathetically, since practical culture means to busy oneself out of habit and to feel a need for occupation.

Georg W. F. Hegel, General outlines of the Philosophy of Right, 1821

Actually one begins to feel […] that this kind of labour is the best police conceivable, because it keeps a tight rein on everybody hindering effectively the evolution of sensibility, aspiration, and the desire for independence. For labour consumes nerve power to an extraordinary extent, depleting the latter as to contemplation, musing, dreaming, concern, love, hatred.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Eulogists of Labour, 1881

10. The working class movement was a movement for labour

The historical working class movement, which did not rise until long after the fall of the old social revolts, did not longer struggle against the impositions of labour but developed an over-identification with the seemingly inevitable. The movement’s focus was on workers‘ „rights“ and the amelioration of living conditions within the reference system of the labour society whose social constraints were largely internalised. Instead of radically criticising the transformation of human energy into money as an irrational end-in-itself, the workers‘ movement took the „standpoint of labour“ and understood capital valorisation as a neutral given fact.

Thus the workers‘ movement stepped into the shoes of absolutism, Protestantism and bourgeois Enlightenment. The misfortune of labour was converted into the false pride of labour, redefining the domestication the fully-fledged working class had went through for the purposes of the modern idol into a „human right“. The domesticated helots so to speak ideologically turned the tables and developed a missionary fervour to demand both the „right to work“ and a general „obligation to work“. They didn’t fight the bourgeois in their capacity as the executives of the labour society but abused them, just the other way around, in the name of labour, by calling them parasites. Without exception, all members of the society should be forcibly recruited to the „armies of labour“.

The workers‘ movement itself became the pacemaker of the capitalist labour society, enforcing the last stages of reification within the labour system’s development process and prevailing against the narrow-minded bourgeois officials of the 19th and early 20th century. It was a process quite similar to what had happened only 100 years before when the bourgeoisie stepped into the shoes of absolutism. This was only possible because the workers‘ parties and trade unions, due to their deification of labour, relied on the state machinery and its institutions of repressive labour management in an affirmative way. That’s why it never occurred to them to abolish the state-run administration of human material and simultaneously the state itself. Instead of that, they were eager to seize the systemic power by means of what they called „the march through the institutions“ (in Germany). Thereby, like the bourgeoisie had done earlier, the workers‘ movement adopted the bureaucratic tradition of labour management and storekeeping of human resources, once conjured up by absolutism.

However, the ideology of a social generalisation of labour required a reconstruction of the political sphere. The system of estates with its differentiation as to political „rights“ (e.g. class system of franchise), being in force when the labour system was just halfway carried through, had to be replaced by the general democratic equality of the finalised „labour state“. Furthermore, any unevenness in the running of the valorisation machine, especially when felt as a harmful impact by society as whole, had to be balanced by welfare state intervention. In this respect, too, it was the workers‘ movement who brought forth the paradigm. Under the name „social democracy“ it became theever largest „bourgeois action group“ in history, but got trapped in its own snare though. In a democracy anything may be subject to negotiation except for the intrinsic constraints of the labour society, which constitute the axiomatic preconditions implied. What can be on debate is confined to the modalities and the handling of those constraints. There is always only a choice between Coca-Cola and Pepsi, between pestilence and cholera, between impudence and dullness, between Kohl and Schröder.

The „democracy“ inherent in the labour society is the ever most perfidious system of domination in history – a system of self-oppression. That’s why such a democracy never organises its members free decision on how the available resources shall be utilised, but is only concerned with the constitution of the legal fabric forming the reference system for the socially segregated labour monads compelled to market themselves under the law of competition. Democracy is the exact opposite of freedom. As a consequence, the „labouring humans“ are necessarily divided into administrators and subjects of administration, employers and employees (in the true sense of the word), functional elite and human material. The inner structures of political parties, applying to labour parties in particular, are a true image of the prevailing social dynamic. Leaders and followers, celebrities and celebrators, nepotism-networks and opportunists: Those interrelated terms are producing evidence of the essence of a social structure that has nothing to do with free debate and free decision. It is a constituent part of the logic of the system that the elite itself is just a dependent functional element of the labour idol and its blind resolutions.

Ever since the Nazis seized power, any political party is a labour party and a capitalist party at the same time. In the „developing societies“ of the East and South, the labour parties mutated into parties of state terrorism to enable catch-up modernisation; in Western countries they became part of a system of „peoples‘ parties“ with exchangeable party manifestos and media representatives. Class struggle is all over because labour society’s time is up. As the labour society is passing away, „classes“ turn out to be mere functional categories of a common social fetish system. Whenever social democrats, Greens, and post-communists distinguish themselves by outlining exceptionally perfidious repression schemes, they prove to be nothing but the legitimate heirs of the workers‘ movement, which never wanted anything else but labour at all cost.

Labour has to wield the sceptre,

Serfdom shall be the idlers fate,

Labour has to rule the world as

Labour is the essence of the world.

Friedrich Stampfer, Der Arbeit Ehre (In Honour of Labour), 1903

11. The crisis of labour

For a short historical moment after the Second World War, it seemed that the labour society, based on Fordistic industries, had consolidated into a system of „eternal prosperity“ pacifying the unbearable end-in-itself by means of mass consumption and welfare state amenities. Apart from the fact that this idea was always an idea of democratic helots – meant to become reality only for a small minority of world population, it has turned out to be foolish even in the capitalist centres. With the third industrial revolution of microelectronics, the labour society reached its absolute historical barrier.

That this barrier would be reached sooner or later was logically foreseeable. From birth, the commodity-producing system suffers from a fatal contradiction in terms. On the one hand, it lives on the massive intake of human energy generated by the expenditure of pure labour power – the more the better. On the other hand, the law of operational competition enforces a permanent increase in productivity bringing about the replacement of human labour power by scientific operational industrial capital.

This contradiction in terms was in fact the underlying cause for all of the earlier crises, among them the disastrous world economic crisis of 1929-33. Due to a mechanism of compensation, it was possible to get over those crises time and again. After a certain incubation period, then based on the higher level of productivity attained, the expansion of the market to fresh groups of buyers led to an intake of more labour power in absolute numbers than was previously rationalised away. Less labour power had to be spent per product, but more goods were produced absolutely to such an extent that this reduction was overcompensated. As long as product innovations exceeded process innovations, it was possible to transform the self-contradiction of the system into an expansion process.

The striking historical example is the automobile. Due to the assembly line and other techniques of „Taylorism“ („work-study expertise“), first introduced in Henry Ford’s auto factory in Detroit, the necessary labour time per auto was reduced to a fraction. Simultaneously, the working process was enormously condensed, so that the human material was drained many times over the previous level in ratio to the same labour time interval. Above all, the car, up to then a luxury article for the upper ten thousand, could be made available to mass consumption due to the lower price.

This way the insatiable appetite of the labour idol for human energy was satisfied on a higher level despite rationalised assembly line production in the times of the second industrial revolution of „Fordism“. At the same time, the auto is a case in point for the destructive character of the highly developed mode of production and consumption in the labour society. In the interest of the mass production of cars and private car use on a huge scale, the landscape is being buried under concrete and the environment is being polluted. And people have resigned to the undeclared 3rd world war raging on the roads and routes of this world – a war claiming millions of casualties, wounded and maimed year in, year out – by just shrugging it off.

The mechanism of compensation becomes defunct in the course of the 3rd industrial revolution of microelectronics. It is true that through microelectronics many products were reduced in price and new products were created (above all in the area of the media). However, for the first time, the speed of process innovation is greater than the speed of product innovation. More labour is rationalised away than can be reabsorbed by expansion of markets. As a logical consequence of rationalisation, electronic robotics replaces human energy or new communication technology makes labour superfluous, respectively. Entire sectors and departments of construction, production, marketing, warehousing, distribution, and management vanish into thin air. For the first time, the labour idol unintentionally confines itself to permanent hunger rations, thereby bringing about its very own death.

As the democratic labour society is a mature end-in-itself system of self-referential labour power expenditure, working like a feedback circuit, it is impossible to switch over to a general reduction in working hours within its forms. On the one hand, economic administrative rationality requires that an ever-increasing number of people become permanently „jobless“ and cut off from the reproduction of their life as inherent in the system. On the other hand, the constantly decreasing number of „employees“ is suffering from overworking and is subject to an even more intense efficiency pressure. In the midst of wealth, poverty and hunger are coming home to the capitalist centres. Production plants are shut down, and large parts of arable land lie fallow. A great number of homes and public buildings are vacant, whereas the number of homeless persons is on the increase. Capitalism becomes a global minority event.

In its distress, the dying labour idol has become auto-cannibalistic. In search of remaining labour „food“, capital breaks up the boundaries of national economy and globalises by means of nomadic cut-throat competition. Entire regions of the world are cut off from the global flows of capital and commodities. In an unprecedented wave of mergers and „hostile takeovers“, global players get ready for the final battle of private entrepeneurship. The disorganised states and nations implode, their populations, driven mad by the struggle for survival, attack each other in ethnic gang wars.

The basic moral principle is the right of the person to his work. […] For me there is nothing more detestable than an idle life. None of us has a right to that. Civilisation has no room for idlers.

Henry Ford

Capital itself is the moving contradiction, [in] that it presses to reduce labour time to a minimum, while it posits labour time, on the other side, as sole measure and source of wealth. […] On the one side, then, it calls to life all the powers of science and of nature, as of social combination and of social intercourse, in order to make the creation of wealth independent (relatively) of the labour time employed on it. On the other side, it wants to use labour time as the measuring rod for the giant social forces thereby created, and to confine them within the limits required to maintain the already created value as value.

Karl Marx, Foundation of the Critique of Political Economy, 1857/8

12. The end of politics

Necessarily the crisis of labour entails the crisis of state and politics. In principle, the modern state owes its career to the fact that the commodity producing system is in need of an overarching authority guaranteeing the general preconditions of competition, the general legal foundations, and the preconditions for the valorisation process – inclusive of a repression apparatus in case human material defaults the systemic imperatives and becomes insubordinate. Organising the masses in the form of bourgeois democracy, the state had to increasingly take on socio-economic functions in the 20th century. Its function is not limited to the provision of social services but comprises public health, transportation, communication and postal service, as well as infrastructures of all kind. The latter state-run or state-supervised services are essential for the working of the labour society, but cannot be organised as a private enterprise valorisation process; „privatised“ public services are most often nothing but state consumption in disguise. The reason for that is that such infrastructure must be available for the society as a whole on a permanent basis and cannot follow the market cycles of supply and demand.

As the state is not a valorisation unit in its own and thus not able to transform labour into money, it has to skim off money from the actual valorisation process to finance its state functions. If the valorisation of value comes to a standstill, the coffers of state empty. The state, purported to be the social sovereign, proves to be completely dependent on the blindly raging, fetishised economy specific to the labour society. The state may pass as many bills as it wants, if the forces of production (the general powers of humanity) outgrow the system of labour, positive law, constituted and applicable only in relation to the subjects of labour, leads nowhere.

As a result of the ever-increasing mass unemployment, revenues from the taxation of earned income drain away. The social security net rips as soon as the number of „superfluous“ people constitutes a critical mass that has to be fed by the redistribution of monetary yields generated elsewhere in the capitalist system. However, with the rapid concentration process of capital in crisis, exceeding the boundaries of national economies, state revenues from the taxation of corporate profits drain away as well. The compulsions thereby exerted by transnational corporations on national economies, who are competing for foreign investment, result in tax dumping, dismantling of the welfare state, and the downgrading of environment protection standards. That is why the democratic state mutates into a mere crisis administrator.

The more the state approaches financial emergency, the more it is reduced to its repressive core. Infrastructures are cut down to proportions just meeting the requirements of transnational capital. As it was once the case in the colonies, social logistics are increasingly restricted to a few economic centres while the rest of the territory becomes wasteland. Whatever can be privatised is privatised, even if more and more people are excluded from the most essential supplies.

When the valorisation of value concentrates on only a few world market havens, a comprehensive supply system to satisfy the needs of the population as a whole does not matter any longer. Whether there is train service or postal service available is only relevant in respect to trade, industry, and financial markets. Education becomes the privilege of the globalisation winners. Intellectual, artistic, and theoretical culture is weighed against the criterion of marketability and fades away. A widening financing gap ruins public health service, giving rise to a class system of medical care. Surreptitiously and gradually at the beginning, eventually with callous candour, the law of social euthanasia is promulgated: Because you are poor and superfluous, you will have to die early.

In the fields of medicine, education, culture, and general infrastructure, knowledge, skill, techniques and methods along with the necessary equipment are available in abundance. However, pursuant to the „subject to sufficient funds“-clause – the latter objectifying the irrational law of the labour society – any of those capacities and capabilities has to be kept under lock and key, or has to be demobilised and scrapped. The same applies to the means of production in farming and industry as soon as they turn out to be „unprofitable“. Apart from the repressive labour simulation imposed on people by means of forced labour and low-wage regime along with the cutback of social security payments, the democratic state that already transformed into an apartheid system has nothing on offer for his ex-labour subjects. At a more advanced stage, the administration as such will disintegrate. The state apparatus will degenerate into a corrupt „kleptocracy“, the armed forces into Mafia-structured war gangs, and police forces into highwaymen.

No policy conceivable can stop this process or even reverse it. By its essence politics is related to social organisation in the form of state. When the foundations of the state-edifice crumble, politics and policies become baseless. Day after day, the left-wing democratic formula of the „political shaping“ (politische Gestaltung) of living conditions makes a fool of itself more and more. Apart from endless repression, the gradual elimination of civilisation, and support for the „terror of economy“, there is nothing left to „shape“. As the social end-in-itself specific to the labour society is an axiomatic presupposition of Western democracy, there is no basis for political-democratic regulation when labour is in crisis. The end of labour is the end of politics.

13. The casino-capitalist simulation of labour society

The predominant social awareness deceives itself systematically about the actual state of the labour society: Collapsing regions are excommunicated ideologically, labour market statistics are distorted unscrupulously, and forms of impoverishment are simulated away by the media. Simulation is the central feature of crisis capitalism anyway. This is also true for the economy itself.

If – at least in the countries at the heart of the Western world – it seems that capital accumulation is possible without labour employed and that money as a pure form is able to guarantee the further valorisation of value out of itself, such appearance is owing to the simulation process going on at financial markets. As a mirror image of labour simulation by means of coercive measures imposed by the labour administration authorities, a simulation of capital valorisation developed from the speculative uncoupling of the credit system and equity market from the actual economy.

Present-time labour employed is replaced by the tapping of future-time labour that will never be employed in reality – capital accumulation taking place in some fictitious future II so to speak. Monetary capital that no longer can profitably be reinvested in active assets, and is therefore unable to consume labour, has increasingly to resort to financial markets.

Even the Fordistic boom of capital valorisation in the heydays of the so-called „economic miracle“ after World War II was not entirely self-sustaining. As it was impossible to finance the basic preconditions of labour society otherwise, the state turned to deficit spending to an unprecedented extent. The credit volume raised exceeded revenue from taxation by far. This means that the state pledged its future actual revenue as a collateral security. On the one hand, this way an investment opportunity for „superfluous“ moneyed capital was created; it was lent to the state on interest. The state settled interest payment by raising fresh credit, thereby funnelling back the borrowed money into economic circulation.

On the other hand, this implies that social security expenditure and public spending on infrastructure was financed by way of credit. Hence, in terms of capitalist logic, an „artificial“ demand was created which was not covered by productive labour power expenditure. By tapping its own future, the labour society prolonged the lifetime of the Fordistic boom beyond its actual span.

This simulative element, being in operation even in times of a seemingly intact valorisation process, came up against limiting factors in line with the amount of indebtedness of the state. „Public debt crisis“ in the capitalist centres as well as in Third World countries put an end to the stimulation of economic growth by means of deficit spending and laid the foundation for the triumphant advance of neo-liberal deregulation policies. According to the liberal ideology, deregulation can only be effected in line with a sweeping reduction of the public-sector share in national product In reality costs and expenses arising from crisis management, whether it is government spending on the repression apparatus or national expenditure for the maintenance of the simulation machinery, do compensate cost saving from deregulation and the reduction of state functions. In many states, the public-sector share even expanded as a result.

However, it was not possible to simulate the further accumulation of capital by means of deficit spending any longer. Consequently, in the eighties of last century, the additional creation of fictitious capital shifted to the equity market. No longer dividend, the share in real profit, is a matter of concern; rather it is stock price gains, the speculative increase in value of the legal title up to an astronomical magnitude, which counts. The ratio of real economy to speculative price movements turned upside down. The speculative price advance no longer anticipates real economic expansion but conversely, the bull market of fictitious net profit generation simulates a real accumulation that no longer exists.

Clinically dead, the labour idol is kept breathing artificially by means of a seemingly self-induced expansion of financial markets. Industrial corporations show profits that don’t come from operating income, i.e. the production and sale of goods – a loss-making branch of business for a long time – but from the „clever“ speculation of their financial departments in stocks and currency. The revenue items shown in the budgets of public authorities are not yielded by taxation or public borrowing, but by the keen participation of fiscal administrations in the financial gambling markets. Families and one-person households whose real income from wages or salaries is dropping dramatically, keep to their spending spree habit by using stocks and prospective price gains as a collateral for consumer credits. Once again, a new form of artificial demand is created resulting in production and revenue „built upon sandy ground“.

The speculative process is a dilatory tactic to defer the global economic crisis. As the fictitious increase in the value of legal titles is only the anticipation of future labour employed (to an astronomical magnitude) that will never be employed, the lid will be taken off the objectified swindle after a certain time of incubation. The breakdown of the „emerging markets“ in Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe was just a first foretaste. It is only a question of time until the financial markets of the capitalist centres in the US, the EU (European Union) and Japan will collapse.

These interrelations are completely distorted by the fetish-awareness of the labour society, inclusive of traditional left-wing and right-wing „critics of capitalism“. Fixated on the labour phantom, which was ennobled to be the transhistorical and positive precondition of human existence, they systematically confuse cause and effect. The speculative expansion of financial markets, which is the cause for the temporary deferment of crisis, is then just the other way around, detected to be the cause of the crisis. The „evil speculators“, they say more or less panic-stricken, will ruin the absolutely wonderful labour society by gambling away „good“ money of which they have more than enough just for kicks, instead of bravely investing it in marvellous „jobs“ so that a labour maniac humanity may enjoy „full employment“ self-indulgently.

It is beyond them that it is by no means speculation that brought investment in real economy to a standstill, but that such investment became unprofitable as a result of the 3rd industrial revolution. The speculative take off of share prices is just a symptom of the inner dynamics. Even according to capitalist logic, this money, seemingly circulating in ever-increasing loads, is not „good“ money any longer but rather „hot air“ inflating the speculative bubble. Any attempt to tap this bubble by means of whatsoever tax (Tobin-tax, etc.) to divert money flows to the ostensibly „correct“ and real social treadmills will most probably bring about the sudden burst of the bubble.

Instead of realising that we all become inexorably unprofitable and therefore the criterion of profitability itself, together with the immanent foundations of labour society, should be attacked as being obsolete, one indulges in demonising the „speculators“. Right-wing extremists, left-wing „subversive elements“, worthy trade unionists, Keynesian nostalgics, social theologians, TV hosts, and all the other apostles of „honest“ labour unanimously cultivate such a cheap concept of an enemy. Very few of them are aware of the fact that it is only a small step from such reasoning to the re-mobilisation of the anti-Semitic paranoia. To invoke the „creative power“ of national-blooded non-monetary capital to fight the „money-amassing“ Jewish-international monetary capital threatens to be the ultimate creed of the intellectually dissolute left; as it has always been the creed of the racist, anti-Semitic, and anti-American „job-creation-scheme“ right.

As soon as labour in the direct form has ceased to be the great well-spring of wealth, labour time ceases and must cease to be its measure, and hence exchange value [must cease to be the measure] of use value. […] With that, production based on exchange value breaks down, and the direct, material production process is stripped of the form of penury and antithesis.

Karl Marx, Foundation of the Critique of Political Economy, 1857/8

14. Labour can not be redefined

After centuries of domestication, the modern human being can not even imagine a life without labour. As a social imperative, labour not only dominates the sphere of the economy in the narrow sense, but also pervades social existence as a whole, creeping into everyday life and deep under the skin of everybody. „Free time“, a prison term in its literal meaning, is spent to consume commodities in order to increase (future) sales.

Beyond the internalised duty of commodity consumption as an end-in-itself and even outside offices and factories, labour casts its shadow on the modern individual. As soon as our contemporary rises from the TV chair and becomes active, every action is transformed into an act similar to labour. The joggers replace the time clock by the stopwatch, the treadmill celebrates its post-modern rebirth in chrome-plated gyms, and holidaymakers burn up the kilometres as if they had to emulate the year’s work of a long-distance lorry driver. Even sexual intercourse is orientated towards the standards of sexology and talk show boasting.

King Midas was quite aware of meeting his doom when anything he touched turned into gold; his modern fellow sufferers, however, are far beyond this stage. The demons for work (labour) even don’t realise any longer that the particular sensual quality of any activity fades away and becomes insignificant when adjusted to the patterns of labour. On the contrary, our contemporaries quite generally only ascribe meaning, validity and social significance to an activity if they can square it with the indifference of the world of commodities. His labour’s subjects don’t know what to make of a feeling like grief; the transformation of grief into grieving-work, however, makes the emotional alien element a known quantity one is able to gossip about with people of one’s own kind. This way dreaming turns into dreaming-work, to concern oneself with a beloved one turns into relationship-work, and care for children into child raising work past caring. Whenever the modern human being insists on the seriousness of his activities, he pays homage to the idol by using the word „work“ (labour).

The imperialism of labour then is reflected not only in colloquial language. We are not only accustomed to using the term „work/labour“ inflationary, but also mix up two essentially different meanings of the word. „Labour“ no longer, as it would be correct, stands for the capitalist form of activity carried out in the end-in-itself treadmills, but became a synonym for any goal-directed human effort in general, thereby covering up its historical tracks.

This lack of conceptual clarity paves the way for the widespread „common-sense“ critique of labour society, which argues just the wrong way around by affirming the imperialism of labour in a positivist way. As if labour would not control life through and through, the labour society is accused of conceptualising „labour“ too narrowly by only validating marketable gainful employment as „true“ labour in disregard of morally decent do-it-yourself work or unpaid self-help (housework, neighbourly help, etc.). An upgrading and broadening of the concept labour shall eliminate the one-sided fixation along with the hierarchy involved.