This article was originally published in The Baffler.

A secret question hovers over us, a sense of disappointment, a broken promise we were given as children about what our adult world was supposed to be like. I am referring not to the standard false promises that children are always given (about how the world is fair, or how those who work hard shall be rewarded), but to a particular generational promise—given to those who were children in the fifties, sixties, seventies, or eighties—one that was never quite articulated as a promise but rather as a set of assumptions about what our adult world would be like. And since it was never quite promised, now that it has failed to come true, we’re left confused: indignant, but at the same time, embarrassed at our own indignation, ashamed we were ever so silly to believe our elders to begin with.

Where, in short, are the flying cars? Where are the force fields, tractor beams, teleportation pods, antigravity sleds, tricorders, immortality drugs, colonies on Mars, and all the other technological wonders any child growing up in the mid-to-late twentieth century assumed would exist by now? Even those inventions that seemed ready to emerge—like cloning or cryogenics—ended up betraying their lofty promises. What happened to them?

We are well informed of the wonders of computers, as if this is some sort of unanticipated compensation, but, in fact, we haven’t moved even computing to the point of progress that people in the fifties expected we’d have reached by now. We don’t have computers we can have an interesting conversation with, or robots that can walk our dogs or take our clothes to the Laundromat.

As someone who was eight years old at the time of the Apollo moon landing, I remember calculating that I would be thirty-nine in the magic year 2000 and wondering what the world would be like. Did I expect I would be living in such a world of wonders? Of course. Everyone did. Do I feel cheated now? It seemed unlikely that I’d live to see all the things I was reading about in science fiction, but it never occurred to me that I wouldn’t see any of them.

At the turn of the millennium, I was expecting an outpouring of reflections on why we had gotten the future of technology so wrong. Instead, just about all the authoritative voices—both Left and Right—began their reflections from the assumption that we do live in an unprecedented new technological utopia of one sort or another.

The common way of dealing with the uneasy sense that this might not be so is to brush it aside, to insist all the progress that could have happened has happened and to treat anything more as silly. “Oh, you mean all that Jetsons stuff?” I’m asked—as if to say, but that was just for children! Surely, as grown-ups, we understand The Jetsons offered as accurate a view of the future as The Flintstones offered of the Stone Age.

Surely, as grown-ups, we understand The Jetsons offered as accurate a view of the future as The Flintstones did of the Stone Age.

Even in the seventies and eighties, in fact, sober sources such as National Geographic and the Smithsonian were informing children of imminent space stations and expeditions to Mars. Creators of science fiction movies used to come up with concrete dates, often no more than a generation in the future, in which to place their futuristic fantasies. In 1968, Stanley Kubrick felt that a moviegoing audience would find it perfectly natural to assume that only thirty-three years later, in 2001, we would have commercial moon flights, city-like space stations, and computers with human personalities maintaining astronauts in suspended animation while traveling to Jupiter. Video telephony is just about the only new technology from that particular movie that has appeared—and it was technically possible when the movie was showing. 2001 can be seen as a curio, but what about Star Trek? The Star Trek mythos was set in the sixties, too, but the show kept getting revived, leaving audiences for Star Trek Voyager in, say, 2005, to try to figure out what to make of the fact that according to the logic of the program, the world was supposed to be recovering from fighting off the rule of genetically engineered supermen in the Eugenics Wars of the nineties.

By 1989, when the creators of Back to the Future II were dutifully placing flying cars and anti-gravity hoverboards in the hands of ordinary teenagers in the year 2015, it wasn’t clear if this was meant as a prediction or a joke.

The usual move in science fiction is to remain vague about the dates, so as to render “the future” a zone of pure fantasy, no different than Middle Earth or Narnia, or like Star Wars, “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.” As a result, our science fiction future is, most often, not a future at all, but more like an alternative dimension, a dream-time, a technological Elsewhere, existing in days to come in the same sense that elves and dragon-slayers existed in the past—another screen for the displacement of moral dramas and mythic fantasies into the dead ends of consumer pleasure.

Might the cultural sensibility that came to be referred to as postmodernism best be seen as a prolonged meditation on all the technological changes that never happened? The question struck me as I watched one of the recent Star Wars movies. The movie was terrible, but I couldn’t help but feel impressed by the quality of the special effects. Recalling the clumsy special effects typical of fifties sci-fi films, I kept thinking how impressed a fifties audience would have been if they’d known what we could do by now—only to realize, “Actually, no. They wouldn’t be impressed at all, would they? They thought we’d be doing this kind of thing by now. Not just figuring out more sophisticated ways to simulate it.”

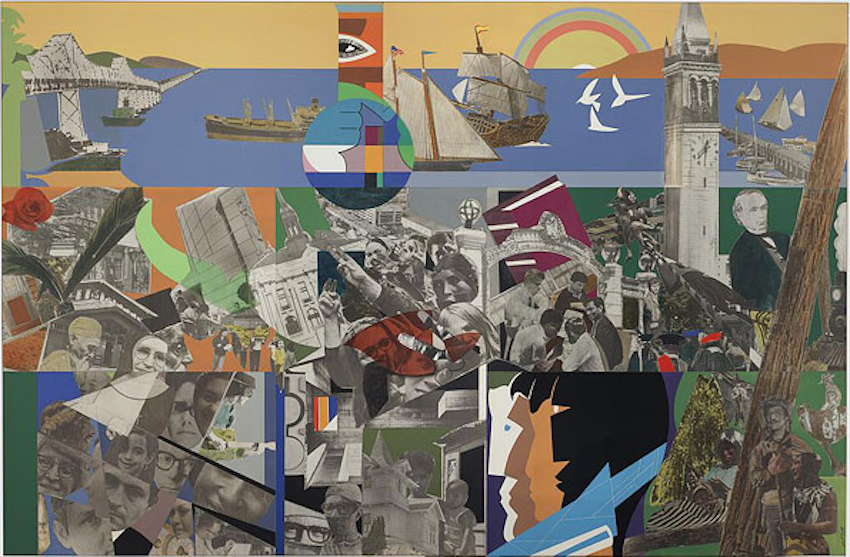

That last word—simulate—is key. The technologies that have advanced since the seventies are mainly either medical technologies or information technologies—largely, technologies of simulation. They are technologies of what Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco called the “hyper-real,” the ability to make imitations that are more realistic than originals. The postmodern sensibility, the feeling that we had somehow broken into an unprecedented new historical period in which we understood that there is nothing new; that grand historical narratives of progress and liberation were meaningless; that everything now was simulation, ironic repetition, fragmentation, and pastiche—all this makes sense in a technological environment in which the only breakthroughs were those that made it easier to create, transfer, and rearrange virtual projections of things that either already existed, or, we came to realize, never would. Surely, if we were vacationing in geodesic domes on Mars or toting about pocket-size nuclear fusion plants or telekinetic mind-reading devices no one would ever have been talking like this. The postmodern moment was a desperate way to take what could otherwise only be felt as a bitter disappointment and to dress it up as something epochal, exciting, and new.

In the earliest formulations, which largely came out of the Marxist tradition, a lot of this technological background was acknowledged. Fredric Jameson’s “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” proposed the term “postmodernism” to refer to the cultural logic appropriate to a new, technological phase of capitalism, one that had been heralded by Marxist economist Ernest Mandel as early as 1972. Mandel had argued that humanity stood at the verge of a “third technological revolution,” as profound as the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, in which computers, robots, new energy sources, and new information technologies would replace industrial labor—the “end of work” as it soon came to be called—reducing us all to designers and computer technicians coming up with crazy visions that cybernetic factories would produce.

End of work arguments were popular in the late seventies and early eighties as social thinkers pondered what would happen to the traditional working-class-led popular struggle once the working class no longer existed. (The answer: it would turn into identity politics.) Jameson thought of himself as exploring the forms of consciousness and historical sensibilities likely to emerge from this new age.

What happened, instead, is that the spread of information technologies and new ways of organizing transport—the containerization of shipping, for example—allowed those same industrial jobs to be outsourced to East Asia, Latin America, and other countries where the availability of cheap labor allowed manufacturers to employ much less technologically sophisticated production-line techniques than they would have been obliged to employ at home.

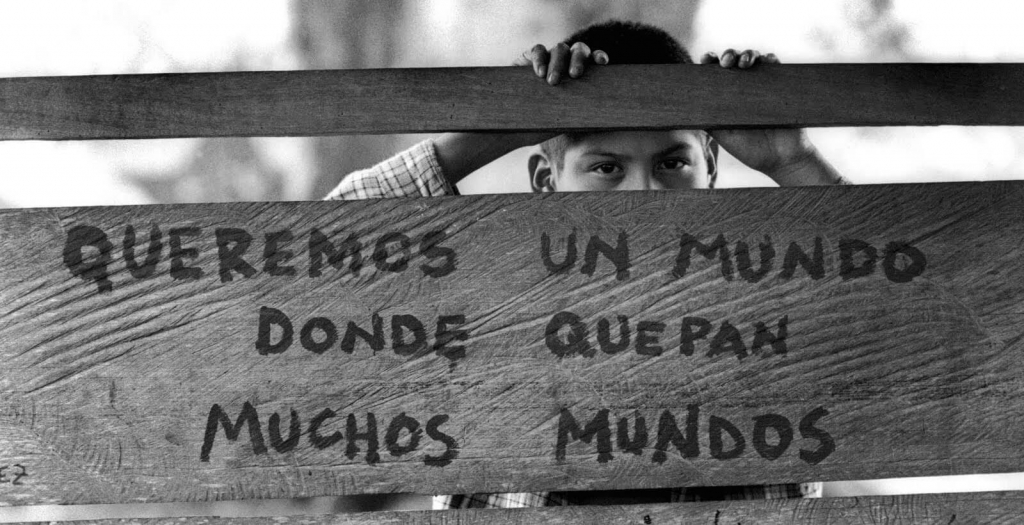

From the perspective of those living in Europe, North America, and Japan, the results did seem to be much as predicted. Smokestack industries did disappear; jobs came to be divided between a lower stratum of service workers and an upper stratum sitting in antiseptic bubbles playing with computers. But below it all lay an uneasy awareness that the postwork civilization was a giant fraud. Our carefully engineered high-tech sneakers were not being produced by intelligent cyborgs or self-replicating molecular nanotechnology; they were being made on the equivalent of old-fashioned Singer sewing machines, by the daughters of Mexican and Indonesian farmers who, as the result of WTO or NAFTA–sponsored trade deals, had been ousted from their ancestral lands. It was a guilty awareness that lay beneath the postmodern sensibility and its celebration of the endless play of images and surfaces.

Why did the projected explosion of technological growth everyone was expecting—the moon bases, the robot factories—fail to happen? There are two possibilities. Either our expectations about the pace of technological change were unrealistic (in which case, we need to know why so many intelligent people believed they were not) or our expectations were not unrealistic (in which case, we need to know what happened to derail so many credible ideas and prospects).

Most social analysts choose the first explanation and trace the problem to the Cold War space race. Why, these analysts wonder, did both the United States and the Soviet Union become so obsessed with the idea of manned space travel? It was never an efficient way to engage in scientific research. And it encouraged unrealistic ideas of what the human future would be like.

Could the answer be that both the United States and the Soviet Union had been, in the century before, societies of pioneers, one expanding across the Western frontier, the other across Siberia? Didn’t they share a commitment to the myth of a limitless, expansive future, of human colonization of vast empty spaces, that helped convince the leaders of both superpowers they had entered into a “space age” in which they were battling over control of the future itself? All sorts of myths were at play here, no doubt, but that proves nothing about the feasibility of the project.

Some of those science fiction fantasies (at this point we can’t know which ones) could have been brought into being. For earlier generations, many science fiction fantasies had been brought into being. Those who grew up at the turn of the century reading Jules Verne or H.G. Wells imagined the world of, say, 1960 with flying machines, rocket ships, submarines, radio, and television—and that was pretty much what they got. If it wasn’t unrealistic in 1900 to dream of men traveling to the moon, then why was it unrealistic in the sixties to dream of jet-packs and robot laundry-maids?

In fact, even as those dreams were being outlined, the material base for their achievement was beginning to be whittled away. There is reason to believe that even by the fifties and sixties, the pace of technological innovation was slowing down from the heady pace of the first half of the century. There was a last spate in the fifties when microwave ovens (1954), the Pill (1957), and lasers (1958) all appeared in rapid succession. But since then, technological advances have taken the form of clever new ways of combining existing technologies (as in the space race) and new ways of putting existing technologies to consumer use (the most famous example is television, invented in 1926, but mass produced only after the war.) Yet, in part because the space race gave everyone the impression that remarkable advances were happening, the popular impression during the sixties was that the pace of technological change was speeding up in terrifying, uncontrollable ways.

Alvin Toffler’s 1970 best seller Future Shock argued that almost all the social problems of the sixties could be traced back to the increasing pace of technological change. The endless outpouring of scientific breakthroughs transformed the grounds of daily existence, and left Americans without any clear idea of what normal life was. Just consider the family, where not just the Pill, but also the prospect of in vitro fertilization, test tube babies, and sperm and egg donation were about to make the idea of motherhood obsolete.

Humans were not psychologically prepared for the pace of change, Toffler wrote. He coined a term for the phenomenon: “accelerative thrust.” It had begun with the Industrial Revolution, but by roughly 1850, the effect had become unmistakable. Not only was everything around us changing, but most of it—human knowledge, the size of the population, industrial growth, energy use—was changing exponentially. The only solution, Toffler argued, was to begin some kind of control over the process, to create institutions that would assess emerging technologies and their likely effects, to ban technologies likely to be too socially disruptive, and to guide development in the direction of social harmony.

While many of the historical trends Toffler describes are accurate, the book appeared when most of these exponential trends halted. It was right around 1970 when the increase in the number of scientific papers published in the world—a figure that had doubled every fifteen years since, roughly, 1685—began leveling off. The same was true of books and patents.

Toffler’s use of acceleration was particularly unfortunate. For most of human history, the top speed at which human beings could travel had been around 25 miles per hour. By 1900 it had increased to 100 miles per hour, and for the next seventy years it did seem to be increasing exponentially. By the time Toffler was writing, in 1970, the record for the fastest speed at which any human had traveled stood at roughly 25,000 mph, achieved by the crew of Apollo 10 in 1969, just one year before. At such an exponential rate, it must have seemed reasonable to assume that within a matter of decades, humanity would be exploring other solar systems.

Since 1970, no further increase has occurred. The record for the fastest a human has ever traveled remains with the crew of Apollo 10. True, the commercial airliner Concorde, which first flew in 1969, reached a maximum speed of 1,400 mph. And the Soviet Tupolev Tu-144, which flew first, reached an even faster speed of 1,553 mph. But those speeds not only have failed to increase; they have decreased since the Tupolev Tu-144 was cancelled and the Concorde was abandoned.

None of this stopped Toffler’s own career. He kept retooling his analysis to come up with new spectacular pronouncements. In 1980, he produced The Third Wave, its argument lifted from Ernest Mandel’s “third technological revolution”—except that while Mandel thought these changes would spell the end of capitalism, Toffler assumed capitalism was eternal. By 1990, Toffler was the personal intellectual guru to Republican congressman Newt Gingrich, who claimed that his 1994 “Contract With America” was inspired, in part, by the understanding that the United States needed to move from an antiquated, materialist, industrial mind-set to a new, free-market, information age, Third Wave civilization.

There are all sorts of ironies in this connection. One of Toffler’s greatest achievements was inspiring the government to create an Office of Technology Assessment (OTA). One of Gingrich’s first acts on winning control of the House of Representatives in 1995 was defunding the OTA as an example of useless government extravagance. Still, there’s no contradiction here. By this time, Toffler had long since given up on influencing policy by appealing to the general public; he was making a living largely by giving seminars to CEOs and corporate think tanks. His insights had been privatized.

Gingrich liked to call himself a “conservative futurologist.” This, too, might seem oxymoronic; but, in fact, Toffler’s own conception of futurology was never progressive. Progress was always presented as a problem that needed to be solved.

Toffler might best be seen as a lightweight version of the nineteenth-century social theorist Auguste Comte, who believed that he was standing on the brink of a new age—in his case, the Industrial Age—driven by the inexorable progress of technology, and that the social cataclysms of his times were caused by the social system not adjusting. The older feudal order had developed Catholic theology, a way of thinking about man’s place in the cosmos perfectly suited to the social system of the time, as well as an institutional structure, the Church, that conveyed and enforced such ideas in a way that could give everyone a sense of meaning and belonging. The Industrial Age had developed its own system of ideas—science—but scientists had not succeeded in creating anything like the Catholic Church. Comte concluded that we needed to develop a new science, which he dubbed “sociology,” and said that sociologists should play the role of priests in a new Religion of Society that would inspire everyone with a love of order, community, work discipline, and family values. Toffler was less ambitious; his futurologists were not supposed to play the role of priests.

Gingrich had a second guru, a libertarian theologian named George Gilder, and Gilder, like Toffler, was obsessed with technology and social change. In an odd way, Gilder was more optimistic. Embracing a radical version of Mandel’s Third Wave argument, he insisted that what we were seeing with the rise of computers was an “overthrow of matter.” The old, materialist Industrial Society, where value came from physical labor, was giving way to an Information Age where value emerges directly from the minds of entrepreneurs, just as the world had originally appeared ex nihilo from the mind of God, just as money, in a proper supply-side economy, emerged ex nihilo from the Federal Reserve and into the hands of value-creating capitalists. Supply-side economic policies, Gilder concluded, would ensure that investment would continue to steer away from old government boondoggles like the space program and toward more productive information and medical technologies.

But if there was a conscious, or semi-conscious, move away from investment in research that might lead to better rockets and robots, and toward research that would lead to such things as laser printers and CAT scans, it had begun well before Toffler’s Future Shock (1970) and Gilder’s Wealth and Poverty (1981). What their success shows is that the issues they raised—that existing patterns of technological development would lead to social upheaval, and that we needed to guide technological development in directions that did not challenge existing structures of authority—echoed in the corridors of power. Statesmen and captains of industry had been thinking about such questions for some time.

Industrial capitalism has fostered an extremely rapid rate of scientific advance and technological innovation—one with no parallel in previous human history. Even capitalism’s greatest detractors, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, celebrated its unleashing of the “productive forces.” Marx and Engels also believed that capitalism’s continual need to revolutionize the means of industrial production would be its undoing. Marx argued that, for certain technical reasons, value—and therefore profits—can be extracted only from human labor. Competition forces factory owners to mechanize production, to reduce labor costs, but while this is to the short-term advantage of the firm, mechanization’s effect is to drive down the general rate of profit.

For 150 years, economists have debated whether all this is true. But if it is true, then the decision by industrialists not to pour research funds into the invention of the robot factories that everyone was anticipating in the sixties, and instead to relocate their factories to labor-intensive, low-tech facilities in China or the Global South makes a great deal of sense.

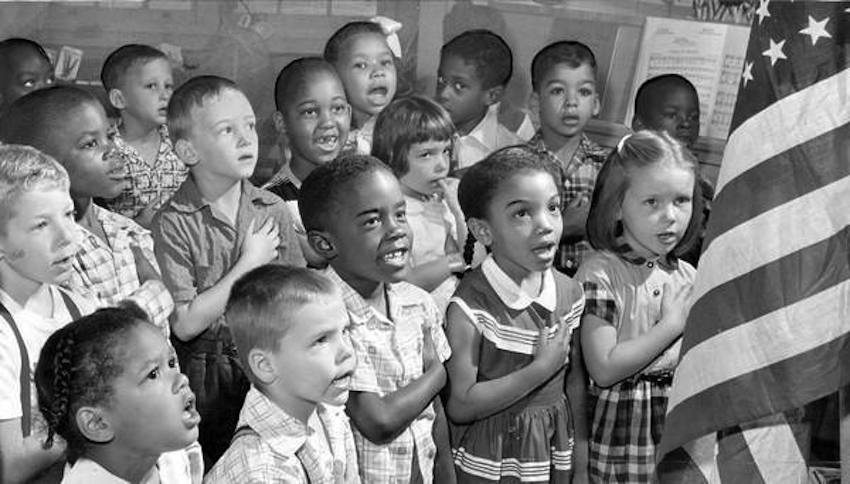

As I’ve noted, there’s reason to believe the pace of technological innovation in productive processes—the factories themselves—began to slow in the fifties and sixties, but the side effects of America’s rivalry with the Soviet Union made innovation appear to accelerate. There was the awesome space race, alongside frenetic efforts by U.S. industrial planners to apply existing technologies to consumer purposes, to create an optimistic sense of burgeoning prosperity and guaranteed progress that would undercut the appeal of working-class politics.

These moves were reactions to initiatives from the Soviet Union. But this part of the history is difficult for Americans to remember, because at the end of the Cold War, the popular image of the Soviet Union switched from terrifyingly bold rival to pathetic basket case—the exemplar of a society that could not work. Back in the fifties, in fact, many United States planners suspected the Soviet system worked better. Certainly, they recalled the fact that in the thirties, while the United States had been mired in depression, the Soviet Union had maintained almost unprecedented economic growth rates of 10 percent to 12 percent a year—an achievement quickly followed by the production of tank armies that defeated Nazi Germany, then by the launching of Sputnik in 1957, then by the first manned spacecraft, the Vostok, in 1961.

It’s often said the Apollo moon landing was the greatest historical achievement of Soviet communism. Surely, the United States would never have contemplated such a feat had it not been for the cosmic ambitions of the Soviet Politburo. We are used to thinking of the Politburo as a group of unimaginative gray bureaucrats, but they were bureaucrats who dared to dream astounding dreams. The dream of world revolution was only the first. It’s also true that most of them—changing the course of mighty rivers, this sort of thing—either turned out to be ecologically and socially disastrous, or, like Joseph Stalin’s one-hundred-story Palace of the Soviets or a twenty-story statue of Vladimir Lenin, never got off the ground.

After the initial successes of the Soviet space program, few of these schemes were realized, but the leadership never ceased coming up with new ones. Even in the eighties, when the United States was attempting its own last, grandiose scheme, Star Wars, the Soviets were planning to transform the world through creative uses of technology. Few outside of Russia remember most of these projects, but great resources were devoted to them. It’s also worth noting that unlike the Star Wars project, which was designed to sink the Soviet Union, most were not military in nature: as, for instance, the attempt to solve the world hunger problem by harvesting lakes and oceans with an edible bacteria called spirulina, or to solve the world energy problem by launching hundreds of gigantic solar-power platforms into orbit and beaming the electricity back to earth.

The American victory in the space race meant that, after 1968, U.S. planners no longer took the competition seriously. As a result, the mythology of the final frontier was maintained, even as the direction of research and development shifted away from anything that might lead to the creation of Mars bases and robot factories.

The standard line is that all this was a result of the triumph of the market. The Apollo program was a Big Government project, Soviet-inspired in the sense that it required a national effort coordinated by government bureaucracies. As soon as the Soviet threat drew safely out of the picture, though, capitalism was free to revert to lines of technological development more in accord with its normal, decentralized, free-market imperatives—such as privately funded research into marketable products like personal computers. This is the line that men like Toffler and Gilder took in the late seventies and early eighties.

In fact, the United States never did abandon gigantic, government-controlled schemes of technological development. Mainly, they just shifted to military research—and not just to Soviet-scale schemes like Star Wars, but to weapons projects, research in communications and surveillance technologies, and similar security-related concerns. To some degree this had always been true: the billions poured into missile research had always dwarfed the sums allocated to the space program. Yet by the seventies, even basic research came to be conducted following military priorities. One reason we don’t have robot factories is because roughly 95 percent of robotics research funding has been channeled through the Pentagon, which is more interested in developing unmanned drones than in automating paper mills.

A case could be made that even the shift to research and development on information technologies and medicine was not so much a reorientation toward market-driven consumer imperatives, but part of an all-out effort to follow the technological humbling of the Soviet Union with total victory in the global class war—seen simultaneously as the imposition of absolute U.S. military dominance overseas, and, at home, the utter rout of social movements.

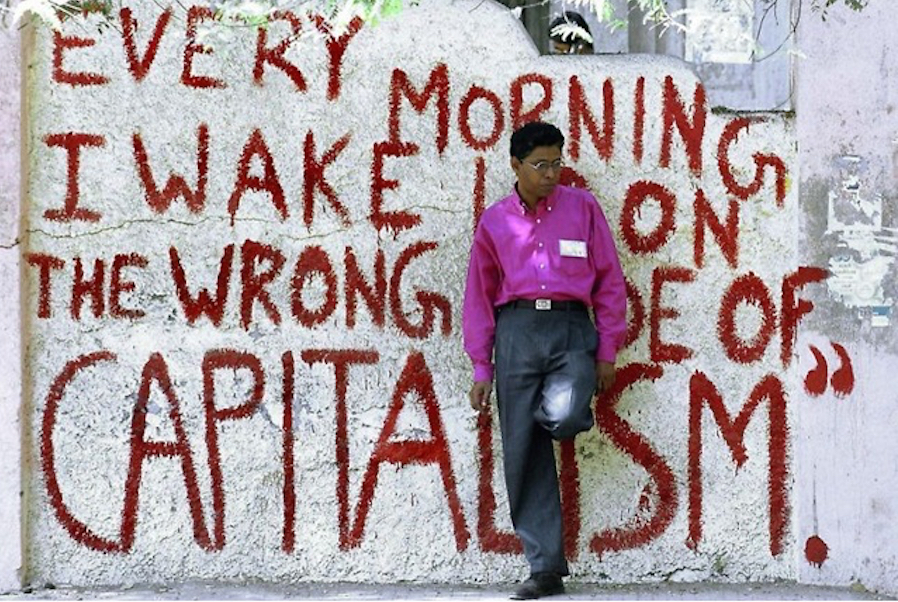

For the technologies that did emerge proved most conducive to surveillance, work discipline, and social control. Computers have opened up certain spaces of freedom, as we’re constantly reminded, but instead of leading to the workless utopia Abbie Hoffman imagined, they have been employed in such a way as to produce the opposite effect. They have enabled a financialization of capital that has driven workers desperately into debt, and, at the same time, provided the means by which employers have created “flexible” work regimes that have both destroyed traditional job security and increased working hours for almost everyone. Along with the export of factory jobs, the new work regime has routed the union movement and destroyed any possibility of effective working-class politics.

Meanwhile, despite unprecedented investment in research on medicine and life sciences, we await cures for cancer and the common cold, and the most dramatic medical breakthroughs we have seen have taken the form of drugs such as Prozac, Zoloft, or Ritalin—tailor-made to ensure that the new work demands don’t drive us completely, dysfunctionally crazy.

With results like these, what will the epitaph for neoliberalism look like? I think historians will conclude it was a form of capitalism that systematically prioritized political imperatives over economic ones. Given a choice between a course of action that would make capitalism seem the only possible economic system, and one that would transform capitalism into a viable, long-term economic system, neoliberalism chooses the former every time. There is every reason to believe that destroying job security while increasing working hours does not create a more productive (let alone more innovative or loyal) workforce. Probably, in economic terms, the result is negative—an impression confirmed by lower growth rates in just about all parts of the world in the eighties and nineties.

But the neoliberal choice has been effective in depoliticizing labor and overdetermining the future. Economically, the growth of armies, police, and private security services amounts to dead weight. It’s possible, in fact, that the very dead weight of the apparatus created to ensure the ideological victory of capitalism will sink it. But it’s also easy to see how choking off any sense of an inevitable, redemptive future that could be different from our world is a crucial part of the neoliberal project.

At this point all the pieces would seem to be falling neatly into place. By the sixties, conservative political forces were growing skittish about the socially disruptive effects of technological progress, and employers were beginning to worry about the economic impact of mechanization. The fading Soviet threat allowed for a reallocation of resources in directions seen as less challenging to social and economic arrangements, or indeed directions that could support a campaign of reversing the gains of progressive social movements and achieving a decisive victory in what U.S. elites saw as a global class war. The change of priorities was introduced as a withdrawal of big-government projects and a return to the market, but in fact the change shifted government-directed research away from programs like NASA or alternative energy sources and toward military, information, and medical technologies.

Of course this doesn’t explain everything. Above all, it does not explain why, even in those areas that have become the focus of well-funded research projects, we have not seen anything like the kind of advances anticipated fifty years ago. If 95 percent of robotics research has been funded by the military, then where are the Klaatu-style killer robots shooting death rays from their eyes?

Obviously, there have been advances in military technology in recent decades. One of the reasons we all survived the Cold War is that while nuclear bombs might have worked as advertised, their delivery systems did not; intercontinental ballistic missiles weren’t capable of striking cities, let alone specific targets inside cities, and this fact meant there was little point in launching a nuclear first strike unless you intended to destroy the world.

Contemporary cruise missiles are accurate by comparison. Still, precision weapons never do seem capable of assassinating specific individuals (Saddam, Osama, Qaddafi), even when hundreds are dropped. And ray guns have not materialized—surely not for lack of trying. We can assume the Pentagon has spent billions on death ray research, but the closest they’ve come so far are lasers that might, if aimed correctly, blind an enemy gunner looking directly at the beam. Aside from being unsporting, this is pathetic: lasers are a fifties technology. Phasers that can be set to stun do not appear to be on the drawing boards; and when it comes to infantry combat, the preferred weapon almost everywhere remains the AK-47, a Soviet design named for the year it was introduced: 1947.

The Internet is a remarkable innovation, but all we are talking about is a super-fast and globally accessible combination of library, post office, and mail-order catalogue. Had the Internet been described to a science fiction aficionado in the fifties and sixties and touted as the most dramatic technological achievement since his time, his reaction would have been disappointment. Fifty years and this is the best our scientists managed to come up with? We expected computers that would think!

Overall, levels of research funding have increased dramatically since the seventies. Admittedly, the proportion of that funding that comes from the corporate sector has increased most dramatically, to the point that private enterprise is now funding twice as much research as the government, but the increase is so large that the total amount of government research funding, in real-dollar terms, is much higher than it was in the sixties. “Basic,” “curiosity-driven,” or “blue skies” research—the kind that is not driven by the prospect of any immediate practical application, and that is most likely to lead to unexpected breakthroughs—occupies an ever smaller proportion of the total, though so much money is being thrown around nowadays that overall levels of basic research funding have increased.

Yet most observers agree that the results have been paltry. Certainly we no longer see anything like the continual stream of conceptual revolutions—genetic inheritance, relativity, psychoanalysis, quantum mechanics—that people had grown used to, and even expected, a hundred years before. Why?

Part of the answer has to do with the concentration of resources on a handful of gigantic projects: “big science,” as it has come to be called. The Human Genome Project is often held out as an example. After spending almost three billion dollars and employing thousands of scientists and staff in five different countries, it has mainly served to establish that there isn’t very much to be learned from sequencing genes that’s of much use to anyone else. Even more, the hype and political investment surrounding such projects demonstrate the degree to which even basic research now seems to be driven by political, administrative, and marketing imperatives that make it unlikely anything revolutionary will happen.

Here, our fascination with the mythic origins of Silicon Valley and the Internet has blinded us to what’s really going on. It has allowed us to imagine that research and development is now driven, primarily, by small teams of plucky entrepreneurs, or the sort of decentralized cooperation that creates open-source software. This is not so, even though such research teams are most likely to produce results. Research and development is still driven by giant bureaucratic projects.

What has changed is the bureaucratic culture. The increasing interpenetration of government, university, and private firms has led everyone to adopt the language, sensibilities, and organizational forms that originated in the corporate world. Although this might have helped in creating marketable products, since that is what corporate bureaucracies are designed to do, in terms of fostering original research, the results have been catastrophic.

My own knowledge comes from universities, both in the United States and Britain. In both countries, the last thirty years have seen a veritable explosion of the proportion of working hours spent on administrative tasks at the expense of pretty much everything else. In my own university, for instance, we have more administrators than faculty members, and the faculty members, too, are expected to spend at least as much time on administration as on teaching and research combined. The same is true, more or less, at universities worldwide.

The growth of administrative work has directly resulted from introducing corporate management techniques. Invariably, these are justified as ways of increasing efficiency and introducing competition at every level. What they end up meaning in practice is that everyone winds up spending most of their time trying to sell things: grant proposals; book proposals; assessments of students’ jobs and grant applications; assessments of our colleagues; prospectuses for new interdisciplinary majors; institutes; conference workshops; universities themselves (which have now become brands to be marketed to prospective students or contributors); and so on.

As marketing overwhelms university life, it generates documents about fostering imagination and creativity that might just as well have been designed to strangle imagination and creativity in the cradle. No major new works of social theory have emerged in the United States in the last thirty years. We have been reduced to the equivalent of medieval scholastics, writing endless annotations of French theory from the seventies, despite the guilty awareness that if new incarnations of Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, or Pierre Bourdieu were to appear in the academy today, we would deny them tenure.

There was a time when academia was society’s refuge for the eccentric, brilliant, and impractical. No longer. It is now the domain of professional self-marketers. As a result, in one of the most bizarre fits of social self-destructiveness in history, we seem to have decided we have no place for our eccentric, brilliant, and impractical citizens. Most languish in their mothers’ basements, at best making the occasional, acute intervention on the Internet.

If all this is true in the social sciences, where research is still carried out with minimal overhead largely by individuals, one can imagine how much worse it is for astrophysicists. And, indeed, one astrophysicist, Jonathan Katz, has recently warned students pondering a career in the sciences. Even if you do emerge from the usual decade-long period languishing as someone else’s flunky, he says, you can expect your best ideas to be stymied at every point:

You will spend your time writing proposals rather than doing research. Worse, because your proposals are judged by your competitors, you cannot follow your curiosity, but must spend your effort and talents on anticipating and deflecting criticism rather than on solving the important scientific problems. . . . It is proverbial that original ideas are the kiss of death for a proposal, because they have not yet been proved to work.

That pretty much answers the question of why we don’t have teleportation devices or antigravity shoes. Common sense suggests that if you want to maximize scientific creativity, you find some bright people, give them the resources they need to pursue whatever idea comes into their heads, and then leave them alone. Most will turn up nothing, but one or two may well discover something. But if you want to minimize the possibility of unexpected breakthroughs, tell those same people they will receive no resources at all unless they spend the bulk of their time competing against each other to convince you they know in advance what they are going to discover.

In the natural sciences, to the tyranny of managerialism we can add the privatization of research results. As the British economist David Harvie has reminded us, “open source” research is not new. Scholarly research has always been open source, in the sense that scholars share materials and results. There is competition, certainly, but it is “convivial.” This is no longer true of scientists working in the corporate sector, where findings are jealously guarded, but the spread of the corporate ethos within the academy and research institutes themselves has caused even publicly funded scholars to treat their findings as personal property. Academic publishers ensure that findings that are published are increasingly difficult to access, further enclosing the intellectual commons. As a result, convivial, open-source competition turns into something much more like classic market competition.

There are many forms of privatization, up to and including the simple buying up and suppression of inconvenient discoveries by large corporations fearful of their economic effects. (We cannot know how many synthetic fuel formulae have been bought up and placed in the vaults of oil companies, but it’s hard to imagine nothing like this happens.) More subtle is the way the managerial ethos discourages everything adventurous or quirky, especially if there is no prospect of immediate results. Oddly, the Internet can be part of the problem here. As Neal Stephenson put it:

Most people who work in corporations or academia have witnessed something like the following: A number of engineers are sitting together in a room, bouncing ideas off each other. Out of the discussion emerges a new concept that seems promising. Then some laptop-wielding person in the corner, having performed a quick Google search, announces that this “new” idea is, in fact, an old one; it—or at least something vaguely similar—has already been tried. Either it failed, or it succeeded. If it failed, then no manager who wants to keep his or her job will approve spending money trying to revive it. If it succeeded, then it’s patented and entry to the market is presumed to be unattainable, since the first people who thought of it will have “first-mover advantage” and will have created “barriers to entry.” The number of seemingly promising ideas that have been crushed in this way must number in the millions.

And so a timid, bureaucratic spirit suffuses every aspect of cultural life. It comes festooned in a language of creativity, initiative, and entrepreneurialism. But the language is meaningless. Those thinkers most likely to make a conceptual breakthrough are the least likely to receive funding, and, if breakthroughs occur, they are not likely to find anyone willing to follow up on their most daring implications.

Giovanni Arrighi has noted that after the South Sea Bubble, British capitalism largely abandoned the corporate form. By the time of the Industrial Revolution, Britain had instead come to rely on a combination of high finance and small family firms—a pattern that held throughout the next century, the period of maximum scientific and technological innovation. (Britain at that time was also notorious for being just as generous to its oddballs and eccentrics as contemporary America is intolerant. A common expedient was to allow them to become rural vicars, who, predictably, became one of the main sources for amateur scientific discoveries.)

Contemporary, bureaucratic corporate capitalism was a creation not of Britain, but of the United States and Germany, the two rival powers that spent the first half of the twentieth century fighting two bloody wars over who would replace Britain as a dominant world power—wars that culminated, appropriately enough, in government-sponsored scientific programs to see who would be the first to discover the atom bomb. It is significant, then, that our current technological stagnation seems to have begun after 1945, when the United States replaced Britain as organizer of the world economy.

Americans do not like to think of themselves as a nation of bureaucrats—quite the opposite—but the moment we stop imagining bureaucracy as a phenomenon limited to government offices, it becomes obvious that this is precisely what we have become. The final victory over the Soviet Union did not lead to the domination of the market, but, in fact, cemented the dominance of conservative managerial elites, corporate bureaucrats who use the pretext of short-term, competitive, bottom-line thinking to squelch anything likely to have revolutionary implications of any kind.

If we do not notice that we live in a bureaucratic society, that is because bureaucratic norms and practices have become so all-pervasive that we cannot see them, or, worse, cannot imagine doing things any other way.

Computers have played a crucial role in this narrowing of our social imaginations. Just as the invention of new forms of industrial automation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had the paradoxical effect of turning more and more of the world’s population into full-time industrial workers, so has all the software designed to save us from administrative responsibilities turned us into part- or full-time administrators. In the same way that university professors seem to feel it is inevitable they will spend more of their time managing grants, so affluent housewives simply accept that they will spend weeks every year filling out forty-page online forms to get their children into grade schools. We all spend increasing amounts of time punching passwords into our phones to manage bank and credit accounts and learning how to perform jobs once performed by travel agents, brokers, and accountants.

Someone once figured out that the average American will spend a cumulative six months of life waiting for traffic lights to change. I don’t know if similar figures are available for how long it takes to fill out forms, but it must be at least as long. No population in the history of the world has spent nearly so much time engaged in paperwork.

In this final, stultifying stage of capitalism, we are moving from poetic technologies to bureaucratic technologies. By poetic technologies I refer to the use of rational and technical means to bring wild fantasies to reality. Poetic technologies, so understood, are as old as civilization. Lewis Mumford noted that the first complex machines were made of people. Egyptian pharaohs were able to build the pyramids only because of their mastery of administrative procedures, which allowed them to develop production-line techniques, dividing up complex tasks into dozens of simple operations and assigning each to one team of workmen—even though they lacked mechanical technology more complex than the inclined plane and lever. Administrative oversight turned armies of peasant farmers into the cogs of a vast machine. Much later, after cogs had been invented, the design of complex machinery elaborated principles originally developed to organize people.

Yet we have seen those machines—whether their moving parts are arms and torsos or pistons, wheels, and springs—being put to work to realize impossible fantasies: cathedrals, moon shots, transcontinental railways. Certainly, poetic technologies had something terrible about them; the poetry is likely to be as much of dark satanic mills as of grace or liberation. But the rational, administrative techniques were always in service to some fantastic end.

From this perspective, all those mad Soviet plans—even if never realized—marked the climax of poetic technologies. What we have now is the reverse. It’s not that vision, creativity, and mad fantasies are no longer encouraged, but that most remain free-floating; there’s no longer even the pretense that they could ever take form or flesh. The greatest and most powerful nation that has ever existed has spent the last decades telling its citizens they can no longer contemplate fantastic collective enterprises, even if—as the environmental crisis demands— the fate of the earth depends on it.

What are the political implications of all this? First of all, we need to rethink some of our most basic assumptions about the nature of capitalism. One is that capitalism is identical with the market, and that both therefore are inimical to bureaucracy, which is supposed to be a creature of the state.

The second assumption is that capitalism is in its nature technologically progressive. It would seem that Marx and Engels, in their giddy enthusiasm for the industrial revolutions of their day, were wrong about this. Or, to be more precise: they were right to insist that the mechanization of industrial production would destroy capitalism; they were wrong to predict that market competition would compel factory owners to mechanize anyway. If it didn’t happen, that is because market competition is not, in fact, as essential to the nature of capitalism as they had assumed. If nothing else, the current form of capitalism, where much of the competition seems to take the form of internal marketing within the bureaucratic structures of large semi-monopolistic enterprises, would come as a complete surprise to them.

Defenders of capitalism make three broad historical claims: first, that it has fostered rapid scientific and technological growth; second, that however much it may throw enormous wealth to a small minority, it does so in such a way as to increase overall prosperity; third, that in doing so, it creates a more secure and democratic world for everyone. It is clear that capitalism is not doing any of these things any longer. In fact, many of its defenders are retreating from claiming that it is a good system and instead falling back on the claim that it is the only possible system—or, at least, the only possible system for a complex, technologically sophisticated society such as our own.

But how could anyone argue that current economic arrangements are also the only ones that will ever be viable under any possible future technological society? The argument is absurd. How could anyone know?

Granted, there are people who take that position—on both ends of the political spectrum. As an anthropologist and anarchist, I encounter anticivilizational types who insist not only that current industrial technology leads only to capitalist-style oppression, but that this must necessarily be true of any future technology as well, and therefore that human liberation can be achieved only by returning to the Stone Age. Most of us are not technological determinists.

But claims for the inevitability of capitalism have to be based on a kind of technological determinism. And for that very reason, if the aim of neoliberal capitalism is to create a world in which no one believes any other economic system could work, then it needs to suppress not just any idea of an inevitable redemptive future, but any radically different technological future. Yet there’s a contradiction. Defenders of capitalism cannot mean to convince us that technological change has ended—since that would mean capitalism is not progressive. No, they mean to convince us that technological progress is indeed continuing, that we do live in a world of wonders, but that those wonders take the form of modest improvements (the latest iPhone!), rumors of inventions about to happen (“I hear they are going to have flying cars pretty soon”), complex ways of juggling information and imagery, and still more complex platforms for filling out of forms.

I do not mean to suggest that neoliberal capitalism—or any other system—can be successful in this regard. First, there’s the problem of trying to convince the world you are leading the way in technological progress when you are holding it back. The United States, with its decaying infrastructure, paralysis in the face of global warming, and symbolically devastating abandonment of its manned space program just as China accelerates its own, is doing a particularly bad public relations job. Second, the pace of change can’t be held back forever. Breakthroughs will happen; inconvenient discoveries cannot be permanently suppressed. Other, less bureaucratized parts of the world—or at least, parts of the world with bureaucracies that are not so hostile to creative thinking—will slowly but inevitably attain the resources required to pick up where the United States and its allies have left off. The Internet does provide opportunities for collaboration and dissemination that may help break us through the wall as well. Where will the breakthrough come? We can’t know. Maybe 3D printing will do what the robot factories were supposed to. Or maybe it will be something else. But it will happen.

About one conclusion we can feel especially confident: it will not happen within the framework of contemporary corporate capitalism—or any form of capitalism. To begin setting up domes on Mars, let alone to develop the means to figure out if there are alien civilizations to contact, we’re going to have to figure out a different economic system. Must the new system take the form of some massive new bureaucracy? Why do we assume it must? Only by breaking up existing bureaucratic structures can we begin. And if we’re going to invent robots that will do our laundry and tidy up the kitchen, then we’re going to have to make sure that whatever replaces capitalism is based on a far more egalitarian distribution of wealth and power—one that no longer contains either the super-rich or the desperately poor willing to do their housework. Only then will technology begin to be marshaled toward human needs. And this is the best reason to break free of the dead hand of the hedge fund managers and the CEOs—to free our fantasies from the screens in which such men have imprisoned them, to let our imaginations once again become a material force in human history.