Originally Published by Society and Space.

Introduction: the walking dead

As daylight broke across the Southeastern Mexican state of Chiapas on 21 December 2012, news cameras fixated on the throngs of tourists that had overtaken the state to witness the ‘end of the world’ purportedly predicted by the ancient Maya. Yet in the cities of Altamirano, Palenque, Las Margaritas, Ocosingo, and San Cristóbal de las Casas reports began to emerge of unusual activity: groups of indigenous people constructing makeshift wood stages atop the back of pickup trucks. Hours later 45 000 masked members of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), all of them Chol, Tzeltal, Mam, Tojolobal, Zoque, and Tzotzil Mayan indigenous peoples, descended on these city centers in perfectly ordered columns. Bystanders stood incredulously in front of the improvised stages waiting for the masked Mayans to make a statement of some sort, but the Zapatistas marched by the thousands across the stages in chilling silence with their left fists in the air. In a matter of hours, the Zapatista contingent had left the city centers in the same silence and with the same much-commented-upon discipline with which they had arrived, leaving many wondering what this—the largest march in the history of Chiapas and the largest mobilization of Zapatistas ever seen—was all about. Late that evening, an equally cryptic five-line message appeared on the EZLN’s website. Signed by Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos for the General Command of the EZLN, it read:

“ To Whom It May Concern: Did you hear that?

That is the sound of your world crumbling.

That is the sound of our world resurging.

The day that was day was night.

And night shall be the day that will be day” (EZLN, 2012a, my translation).

In a communiqué a few days later, the Zapatistas would further aid us in unraveling the mystery surrounding their actions of 21 December 2012, stating that what others had mistaken for prophecy (that is, ‘the end of the world’), they had set out to make promise (that is, ending this world) (EZLN, 2012b).

Amazingly, just months before their massive ‘End of the World’march, the EZLN had been declared all but dead by a number of sectors of Mexican society. In this paper I will attempt to fill a lacuna in Anglophone academic discourse by offering a comprehensive analysis of the events surrounding both the ‘death’ and ‘resurgence’ of the EZLN. The paper is divided into two major sections. The first, titled “The death of the EZLN? Or the death of Mexico?” begins with an examination of the way in which, after an explicitly ‘anticapitalist’ reorientation of its political strategy in the early to mid-2000s, the EZLN became radically isolated from the ‘progressive’ and institutional left in Mexican society and was effectively declared dead by the Mexican government. In order to understand the epochal societal shifts that made the EZLN’s strategic reorientation necessary, I examine the contemporary decomposition of Mexico that began with the evisceration of communal land tenure and Article 27 of the Mexican constitution, opening it to the destructive dynamics of neoliberal reterritorialization. Having laid out the end of the social contract that had made ‘the people of Mexico’ a reality, I end this first section by outlining the contemporary growth of legal exceptionality in Mexico and of political rule through the terror that now engulfs the country with the full complicity of the entire Mexican political class. In the second major section of this paper, “Life after death: how the EZLN proposes to build postcapitalism”, I develop three major points through a close reading of Zapatista texts and a firsthand account of contemporary Zapatista political institutions. First, I show that the EZLN, through a systematic analysis of the structural crisis of capitalism, both foresaw and explained the situation that now grips Mexico and increasingly, according to the Zapatistas, the rest of the world. Second, I analyze the way that the EZLN, by adding new dimensions to the ‘geometry’ of political struggle, is able to conceptualize a ‘world’ in the here and now beyond that of neoliberal capitalism, potentially freeing political thought and action far beyond Chiapas from the mutually reinforcing dead ends of either reviving neoliberal capitalism or falling into apocalyptic despair. Finally, through a brief personal narrative of my own experience in 2013 as a student of what the Zapatistas termed their ‘Little School’, I examine the ways in which the Zapatistas’ political strategy, based on the construction of alternative institutionality, has been intimately tied to the practices of building what they call ‘another geography’. This construction of new nonseparatist territorial practices has today been taken up by other organizations across Mexico and increasingly overlaps and contradicts the territories of neoliberal calculation and destruction. I argue that these Zapatista ‘other geographies’ might serve as concrete examples of a viable anticapitalist spatial strategy and therefore must be taken far more seriously than they have been by the left generally and critical geography more specifically.

Section I: the death of the EZLN? Or the death of Mexico?

A Chronicle of a death foretold

The EZLN is today still most widely known for its 1 January 1994 uprising against the Mexican government. Those twelve days of armed action turned out to be one of the first volleys in what would become a generalized region-wide wave of resistance against the ever-deepening consolidation of an incredibly unstable and brutal neoliberal project in Latin America (Reyes, 2012). The EZLN’s uprising soon gave way to negotiations with the Mexican government and the then ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI)—negotiations that from the very beginning centered on the EZLN’s demand for the reintroduction of the de jure protection of collective land tenure that had been eviscerated as a condition of Mexico’s entry into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Through these negotiations the EZLN’s struggle became a central rallying point for a wide panoply of opponents of neoliberal ‘reform’ in Mexico, from radical unions to debtors’ organizations, from indigenous and peasant organizations to the progressive elements of Mexico’s ‘left of center’ Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD).

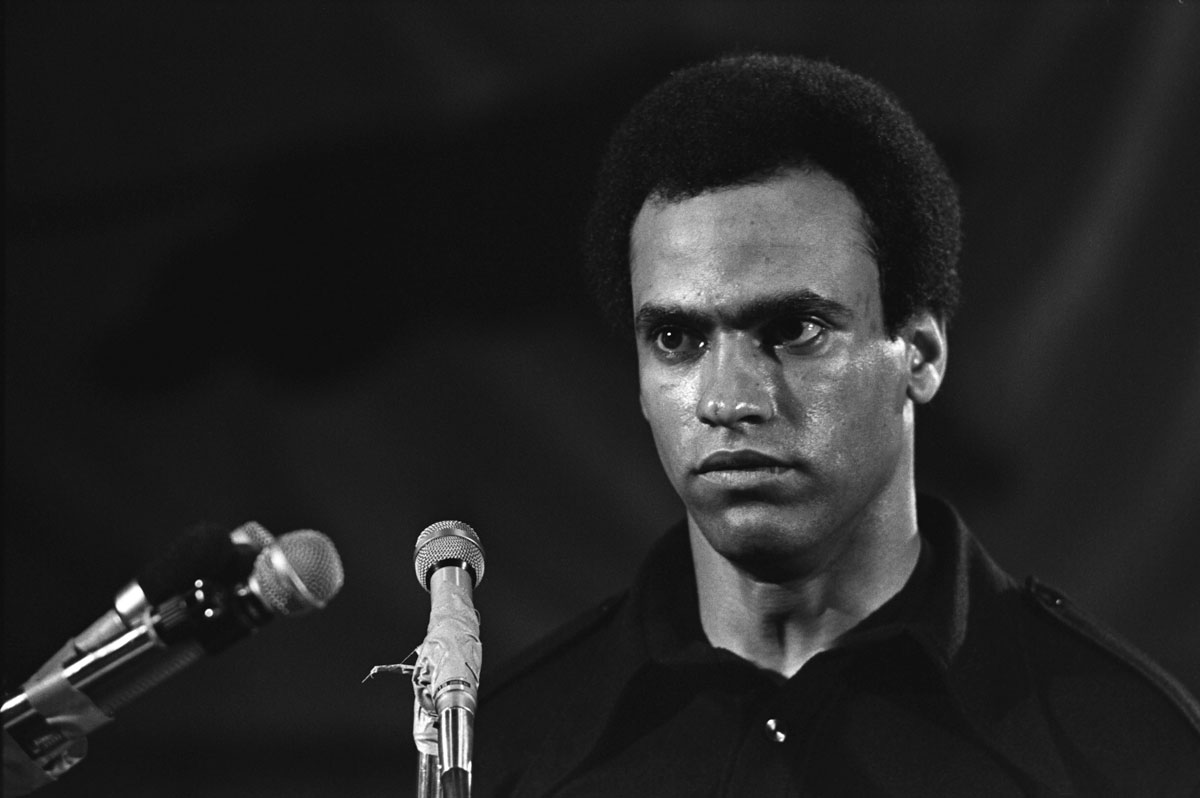

In order to achieve this, the Zapatistas chose to develop (at least publicly) a discursive strategy centered on the voice andimage of Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos. In formulations that suggestively parallel Ernesto Laclau’s (1996) analysis regarding the political centrality of the “empty signifier”, the Zapatistas describe their discursive strategy as an attempt to construct the figure of ‘Marcos’ as a placeholder for the desires of the widest swath of Mexican society possible. As the EZLN notes, at that time there was a ‘Marcos’ for every occasion and every political persuasion (EZLN, 2014a). Mexican society took up this figure as their own, as could be evidenced by the highly popular refrain of “Todos somos Marcos”. This was a phrase that had the virtue of illustrating precisely the political potential of the empty signifier, in that in Spanish it simultaneously denotes this figure’s power to unite (“We are all Marcos”) and premises that space of unity on radical social dispersal (“Marcos is all of us”). The Zapatistas hoped, then, that through this empty signifier an extremely fragmented Mexican ‘civil society’ might unite against the common neoliberal enemy embodied by the PRI. The figure of ‘Marcos’ was thus the placeholder for the ‘counter-hegemony of the diverse’ (page 402) that would seek not so much to impose ‘a revolution’ as to coordinate the forces inside and outside of the state in order to build a space of egalitarian articulation (Rabasa, 1997). This would be a ‘radical democracy’ (page 418) where the direction and purpose of that future revolution might be disputed by Mexican ‘civil society’ (Rabasa, 1997). Importantly, through this discursive strategy, the EZLN’s influence at the time was such that, as the Mexican analyst Luis Hernández Navarro (2013) reminds us, its uprising and subsequent opposition was the single largest (but not the only) reason for the eventual fall of the PRI’s seventy-year dictatorship.

Salinas de Gortari and his PRI successors, for their part, eschewed serious negotiation with the EZLN and sought instead to isolate the EZLN through a counterinsurgency plan detailed in the Mexican Secretary of Defense’s Plan de Campaña Chiapas 94 that included the formation of paramilitary organizations in Zapatista-influenced regions, as well as the targeted use of government subsidies to divide Zapatista communities.(1)

In 2001, with the PRI out of presidential office for the first time in seventy years, the Zapatistas took their initiative for Constitutional Reforms on Indigenous Rights and Culture across Mexico in what they termed ‘The march of the color of the earth’. Millions of Mexicans, with representatives from fifty-six of Mexico’s indigenous peoples and more than a few internationals, came out in an overwhelming show of support for this new initiative. The march culminated on 11 March 2001, with over a million Zapatista supporters filling Mexico City’s enormous Zócalo. The magnitude of support for the event generated widespread expectation that at least some versions of the Zapatistas’ proposed reforms would be approved by the Mexican legislature and signed by then President Vicente Fox. Despite widespread support for their initiative, the Zapatistas’ efforts at constitutional reform met with utter failure as all three major political parties in the Mexican senate—the right-wing National Action Party (PAN), the center-right PRI, and, most surprisingly, the institutional ‘left’ represented by the PRD—joined together to oppose the EZLN’s constitutional reforms. Thus, after years of (at least outwardly) crafting a national counterhegemonic project, what had been the Zapatistas’ discursive strategy up until that point reached an obvious dead end. Many analysts believed at the time that the EZLN would simply return to Chiapas and limit its activities to its communities of influence while leaving questions of national political power to others. More specifically, much of the ‘progressive’ left in Mexico imagined that the EZLN would support the growing strength of the electoral left embodied in the PRD—a party that many in Mexico imagined would come to power in direct parallel to the rise of counterhegemonic ‘progressive governments’ throughout the rest of Latin America. Much to their dismay, the EZLN instead released the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle on 25 June 2005, explicitly severing all ties to the entire Mexican political class. Most surprisingly, it definitively and harshly distanced itself from the presidential campaign of the PRD’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), noting that it could not and would not partake in the ‘change’ that the electoral left imagined he embodied. The EZLN reasoned that the PRD had explicitly worked to defeat the Zapatistas’ initiative on constitutional reforms, that PRD officials (the great majority of them ex-PRI operatives) had partaken in counterinsurgent actions against the Zapatistas, and most importantly, that the PRD and AMLO had explicitly made their peace with the international neoliberal order (EZLN, 2005a). AMLO had praised the PAN’s Vicente Fox for having achieved what he termed ‘macroeconomic equilibrium’ (specifically referring to the neoliberal axioms of reduced deficit spending and low inflation) for Mexico. AMLO vowed to maintain that ‘equilibrium’ and asserted that “State action does not suffocate the [private] initiative of civil society” (Petrich, 2011). Thanks to documents obtained by Wikileaks, we know such statements had their desired effect, if only with the US embassy in Mexico. In an aptly titled cable, “AMLO: Apocalypse Not”, US ambassador Tony Garza concluded that AMLO was “putting the correct pieces into place” and that among its proposed cabinet members, “none of them are radicals.” In fact, subsequent US embassy cables go on to speculate that much of AMLO’s ‘populism’ was simply ‘campaign rhetoric’, and that when faced with proposals emanating from within left sectors of Mexico’s political class, the embassy reassured Washington, “We don’t think AMLO will support these more radical ideas” (Petrich, 2011, page 2).

Yet the Zapatistas did not read the PRD’s political betrayal as an attack solely on them, nor as the result of the personal failings of AMLO. As would later become evident, they saw their predicament as a clear sign of the arrival of a new objective political situation in Mexico as a whole. On the basis of what they had learned over previous years, they stated, “we rose up against a national power only to realize that that power no longer exists … what exists is a global power that produces uneven dominations in different locations, what we are up against is finance capital and speculation” (Zapatista 1999). This realization, then, required a new strategic outlook for Zapatismo, one whose tone was captured by Subcomandante Marcos when he stated, “we no longer make the distinctions we once made [among the Mexican political class], between those who are bad and those who are better. No, they are all the same” (Castellanos, 2008, page 54).

As a direct contestation to the political class, the Zapatistas set out in 2006 on what they called ‘the other campaign’. This was neither an initiative for any of the existing presidential candidates nor a call for abstention. Rather, it was a campaign to highlight the need to build an explicitly anticapitalist organization across Mexico that would in effect create what they called ‘another politics’ and thus act as a counterforce to the alliance of the political class and capitalism. The Zapatistas predicted that many of their former supporters would quickly turn on them and staunchly defend the presidential candidacy of AMLO and electoralism more generally. In fact, they were so certain of this outcome that they wrote a preemptive ‘(non)farewell’ letter addressed to ‘civil society’ attempting to explain their position and, in a sense, publicly foretelling their impending death (EZLN, 2005b). Their intuition proved correct: Mexico’s institutional left was flabbergasted, and reactions to the EZLN’s new initiatives were swift and often vicious. The isolation of the EZLN from the institutional left would only become more severe when, after what was almost certainly electoral fraud during the 2006 presidential election (Díaz-Polanco, 2012)—the mechanics of which were detailed and roundly denounced by Subcomandante Marcos live on radio the day after the election(2)—some on the electoral left went so far as to tie the EZLN’s critique to AMLO defeat (Rodriguez Araujo, 2006). Subsequently, coverage of the EZLN and EZLN communiqués all but disappeared from Mexico’s ‘progressive’ press. From that point on, it was not uncommon to encounter among the institutional left and its progressive allies (especially in Mexico City), the idea that “the EZLN no longer exist[ed].”(3)

Upon assuming the presidency in December of 2006, Felipe Calderón of the right-wing PAN quickly seized upon the EZLN’s political isolation. Calderón designated a long-time PAN operative, the nonindigenous Luis H Álvarez, as Director of the Office of Indigenous Development. Álvarez by his own account spent much of his initial years in this post trying to mount what he termed a ‘peaceful’ counterinsurgency strategy in Chiapas. Álvarez’s strategy in effect served as an intensification of the counterinsurgency strategy Plan Chiapas 94. By directing federal subsidies toward Zapatista communities that would agree to leave the organization (and thereby abandon its policy of not accepting government money), Álvarez hoped to pull the EZLN base away from its leadership, a strategy that by 2012 Álvarez claimed had been a resounding success.

With the release of Álvarez’s book Indigenous Heart: Struggle and Hope of the Original Peoples of Mexico in June 2012, the narrative of the supposed demise of the EZLN that circulated within the political class reached its peak (only a few months before the Zapatistas’ thunderous reappearance on 21 December 2012). The book release became a celebration and a funeral of sorts, organized in order to show the Mexican nation the body of the defunct EZLN via live stream. Both Calderón and an ecstatic Álvarez openly reveled in the disappearance of the EZLN and personally took credit for resolving what they called the ‘indigenous problem’ in Chiapas. If the EZLN had, as Álvarez and Calderón claimed, in effect been killed off, the body of EZLN spokesperson and military strategist Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos stood in for the EZLN as a whole. According to Álvarez, reading aloud from his book, as Marcos languished in the throes of terminal lung cancer, he had, unbeknownst to the rest of the EZLN, approached the Mexican government for medical help that would save him. According to another story, circulated by the Al Jazeera News Network, Subcomandante Marcos was about to suffer what must certainly be the only fate worse than death for a Latin American guerrilla leader: he had accepted an offer to leave the EZLN and live out his life as a professor in a small town in upstate New York (Arsenault, 2011).(4)

In sum, for Mexico’s traditional political class, its ‘progressive’ left, and many of their would-be international supporters, as of mid-2012 the Zapatistas and their spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos were as good as dead.

B. Neoliberal reterritorialization: the death of Mexico?

From the late 1980s to 2000 the PRI, still operating as a de facto state party, attempted to implement a series of structural reforms to privatize electricity, education, collectively held lands, and the national oil industry and thus erode the mechanisms of redistribution that had been established by the postrevolutionary constitution of 1917. This initial set of reforms was touted by the PRI, and more specifically by Carlos Salinas de Gortari, as the dawn of a bright new neoliberal era for Mexico.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, under the advisement of the World Bank and in preparation for the upcoming NAFTA, the burgeoning neoliberal establishment in Mexico viewed the collective forms of land tenure as the key impediment to foreign direct investment and ‘economic growth’.(5) These forms of inalienable, imprescriptible, and nontransferrable land tenure—ejidos and bienes comunales—had been protected by Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution. Article 27 had also granted agrarian communities rights over common-use lands and their resources, making all natural resources found in the subsoil property of the nation. Through changes to Article 27 that opened communal land to rent, sale, and use as collateral to obtain commercial credit, and through state programs such as PROCEDE(6) providing economic subsidies in exchange for the individual ‘certification’ of collective lands (the first step in a process that it was hoped would end in private titles), the PRI took direct aim at what they viewed as the least ‘income-yielding’ sector of the Mexican economy.

If we take up the legal theorist Carl Schmitt’s (2003) lesson that all political ideas imply a particular spatial order and vice versa, there is no single piece of legislation in postrevolutionary Mexico that embodies this precept as obviously as Article 27 of the Mexican constitution. The territorial reordering implied in attacks on ejidal and communal land that were frequently discussed in terms of simple ‘economic’ expediency were in fact nothing short of a direct attack on the postrevolutionary political status quo that had tenuously reigned in Mexico since 1917.

Postrevolutionary Mexico’s capitalist fractions had hoped to contain the threat of radical forces such as those of Emiliano Zapata’s Ejército Libertador del Sur by creating a territorial order that would provide the material and symbolic suture between capitalist economic growth, the institutions of state mediation, and the majority of the Mexican people understood as peasant laborers. They did this by placing the ejido (and the productive labor therein) at the very center of the postrevolutionary juridical order. In effect, I think we must understand Article 27 as the space and juridical ground upon which the constitutional entity of ‘the Mexican people’ found its material existence beyond that of an abstract existential entity, beyond that of an ‘identity’. Article 27 contained the specific spatial ordering in which ‘the people’ (be they capitalists or Zapatistas) could (co)exist in a clearly hierarchical but (potentially) redistributionist truce.

In this way, Mexico prefigured in an agricultural context what Antonio Negri calls the ‘constitutions of labor’ formed in the factory-centered societies of Europe and the United States after the Second World War. In these societies, labor (in the case of Mexico, agrarian labor) is recognized as both the basis of social valorization and “the source of institutional and constitutional structures” (Negri, 1994).(7) Importantly, then, when all three major political parties struck down the EZLN’s initiative to revive Article 27 through the Constitutional Reforms on Indigenous Rights and Culture, this was not due solely to the fact that the Mexican political class desired to exclude the indigenous peoples of Mexico from ‘the Mexican people’. It was also due to the far more novel situation in which the Mexican political class, through its complete abandonment of the territorial ordering implied in Article 27, was now willing to openly acknowledge that the breakdown of the postrevolutionary mediational state was in fact irreversible. The actions of the political class were alerting all of Mexico (although few outside of the EZLN seemed to notice) to the fact that the death of ‘the Mexican people’ had already taken place, and that no one can be included or excluded from something that no longer exists.

C. Terror as strategy

By the mid-2000s, and despite enormous efforts such as PROCEDE and cuts to agricultural subsidies, it became clear that the great majority of collective landholders in Mexico refused to give up their collective titles, preferring even to rent out their land in order to generate income rather than modify its collective character (de Ita, 2006). This led actors within the World Bank, the ever-interventionist community of US military analysts, and the Mexican political class to assert that before further neoliberal reforms could succeed, the longstanding efforts to dismantle collective land tenure would have to be redoubled (Bessi and Navarro, 2014; World Bank, 2001).

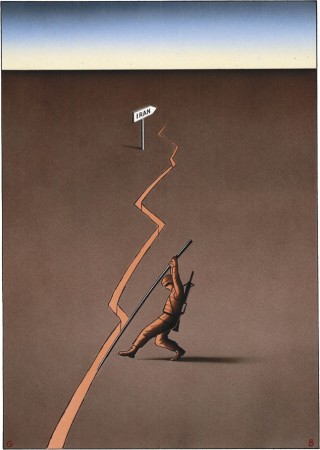

At the very moment when the Mexican state was reinforcing its efforts to cut back social programs for, and mediational presence in, agricultural communities, an increasingly unprotected workforce was coming into contact with the transnational drug economy. That burgeoning economy not only sought to use Mexico as a transportation corridor for South American cocaine headed for the US, but also looked to amass the land, workforce, and transportation infrastructure necessary to make Mexico the fastest growing producer and supplier of heroin and methamphetamines for US consumption (Watt and Zepeda, 2012, pages 76–83). Thus, the reterritorialization implicit in the changes to Article 27 abutted and abetted the territorial reorganization required by the increasing competition for land, transportation routes, and profits within the illicit drug trade.

Although competition for the high-yielding speculative profits of this illicit trade are bound to involve heightened levels of violence, many today believe that Calderón’s policy response to the growth of the drug trade—the rollout of a full-blown ‘war on drugs’—did not arise from the existence or nature of the drug trade itself. As the academic and military affairs analyst Carlos Fazio hypothesizes, Calderón, in conjunction with the US State Department, circulated the notion that the illicit drug trade amounted to a ‘narco-insurgency’, a rogue ‘parallel state’ in the making. This narrative, Fazio believes, served to propagate the idea that the widespread militarization of Mexican society was absolutely necessary in order to neutralize the threat from what Calderón called a burgeoning ‘internal enemy’ (Fazio, 2013). The danger posed by this ‘internal enemy’ in turn justified the nullification of constitutional measures that prohibited the Mexican military from fulfilling domestic police functions, as well as the implicit cancellation of civil liberties and due process this would imply on a daily basis in the country’s streets. For Fazio (2013, pages 371–406) then, this ‘war’ would necessarily amount to nothing less than the de facto imposition of a ‘state of exception’ in in which as Giorgio Agamben (2005) explains, the application of the norm is suspended, “while the law remains in force” (page 31).

Notably, after Calderón’s declaration of a war on drugs and the consolidation of a state of exception, the drug trade in Mexico actually flourished. Consider, for example, the fact that between 2006 and 2012 the production of heroin and marijuana grew and the production of methamphetamines absolutely exploded, while at the same time fewer poppy fields and marijuana plants were destroyed and seizures of cocaine went down. Consequently, six years after Calderón’s war on drugs began, Mexico had become the single largest point of production and transportation for the illicit drug trade in the Americas (Hernández, 2013a).

If the growing state of exception seemed to leave the drug trade untouched, it did result in what Le Monde called “the most deadly conflict on the planet in the last few years”: between 80 000 and 150 000 dead, approximately 30 000 more disappeared, and some 1.5 million people forcibly displaced (Hernández, 2013a, pages 9–13). As Melissa Wright has pointed out, rather than provoking outrage, these grim statistics seemed to have become the very foundation of the Mexican state’s new efforts at legitimation. That is, given its inability to provide the redistributive benefits of past decades, the new Mexican state began to redefine social progress by shifting from a discourse of national development to that of national ‘security’. Within this new discourse of security, the Mexican state now functions under the assumption that all those killed in drug-related violence should be presumed elements of the ‘narco-insurgency’. Therefore, the worse these drug-related statistics become, the greater the proof that the Mexican state has fulfilled its duty to protect the population from this growing internal threat (Wright, 2011, pages 285–298).

Given this apparent shift from the discourse of development to that of security, Fazio and the Mexican sociologist Raquel Gutierrez (among others) believe it is a mistake to simply discount the Mexican state’s war on drugs as a failure. These analysts believe that in addition to providing the basis for a new form of state legitimation, this ‘war’ is best understood as a direct response to the antineoliberal resistance that immediately preceded the war on drugs. It is important to remember that the package of neoliberal reforms from the late 1980s onwards was met with an uncoordinated yet unprecedented wave of resistance across Mexico (Gilly et al, 2006). Although this is rarely acknowledged, this wave of antineoliberal resistance or ‘generalized social insubordination’ to neoliberalism proved to be the determining political factor in Mexico for years to come, just as in the rest of Latin America (Gutierrez Aguilar, 2005; Reyes, 2012). In fact, these scholars argue that the actions of the Mexican political class in the last two decades can be understood only when viewed as a counteroffensive to this resistance. More specifically, these analysts claim that the purpose of this war on drugs was to neutralize these struggles in three very specific ways. First, the inordinate amount of violence this ‘war’ unleashed allowed the Mexican political class to conjoin politics and terror—to practice politics as terror—which in turn created a sense of fear and social isolation among Mexico’s residents and undermined the web of alternative socialities that had subtended antineoliberal resistance (Fazio, 2013, pages 377–380). Second, the social fragmentation produced by the generalization of fear in the war on drugs had the ‘benefit’ of breaking down Mexican society’s capacity to come to a general understanding of what was actually taking place (of what was what, and who was who). As Gutierrez explains, this in turn opened the possibility that instead of the political ‘cooptation’ that had characterized the counterinsurgency practices of the PRI dictatorship, today’s counterinsurgency (sans redistributionary mechanisms) might instead consist of sowing ‘confusion’ so that the very reasons for struggle are irretrievably lost, even to social movements themselves (Brighenti, 2013). Finally, on the ground across Mexico, the war on drugs allowed for coordinated action of state and paramilitary forces—under the orders of the political class, drug cartels, and transnational corporations—against community-level resistance (Lopez y Rivas, 2014). As a perfect illustration of Gutierrez’s point regarding the political deployment of confusion, these forces are often presented to the public by state officials and the media as grassroots community movements that have arisen against the power of drug cartels.

Given the effects of these strategies, the political class now felt prepared to square the macabre circle of neoliberal policy in Mexico. In December 2012, after twelve years of absence, the PRI, through Enrique Peña Nieto, returned to the presidency. In what has been referred to as a ‘lightning’ strategy, and counting on the weakening of antineoliberal resistance, Peña Nieto once again presented the longstanding proposals for the privatization of oil, education, and health care, the further evisceration of protection of collective land tenure, the elimination of the progressive elements of the federal tax code, and the deregulation of labor law. Amidst the giddiness of a reactivated neoliberal offensive (as well as an unmentioned 25 000 drug- war-related deaths during his first year in office), TIME magazine concluded Peña Nieto and this package of reforms were poised to ‘save Mexico’ (Crowley and Mascareñas, 2014). This time around, and unlike in the mid-1990s, the Mexican political class as a whole stood shoulder to shoulder with the core of PRI policy. In fact, within weeks of the PRI’s return to the presidency, all three major political parties (PAN, PRI, and PRD) signed the ‘national pact for Mexico’. The ‘national pact’ was an outline agreement of how these parties would cooperate in the Mexican legislature and senate to finally achieve the neoliberal reforms that had been slowed by the resistance of the past decades. For many, the PRD’s participation in Peña Nieto’s neoliberal ‘pact’ made it painfully clear where the left’s electoralist strategy in Mexico had led: in the words of PRD founder Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, the PRD and the electoral left in Mexico as a whole had over the last two decades “accomplished everything [they had] set out to oppose” (Villamil, 2013, page 32).

Importantly then, the Mexico that the EZLN marched ‘back’ into on 21 December 2012 was not the same country. Rather, the tendencies toward national decomposition pointed out long ago by the EZLN had clearly taken a devastating toll on Mexican society. As became clear to the rest of the world through the much-publicized case of Ayotzinapa, Guerrero (Gibler, 2015), the consequences of this social disintegration have been grave: the death of ‘the Mexican people’, the generalization of terror, the weakening of antineoliberal resistance, a fully complicit institutional left, and tens of thousands of dead and disappeared. Given this context, it is no exaggeration to suggest that, in its rush to bury the Zapatistas, the ‘progressive’ left neglected to ask itself if throughout those same years it was not Mexico itself that was slowly dying.

Section II: life after death: how the EZLN proposes to build postcapitalism

A. The world that is crumbling

Despite the disastrous role of the electoral left in both legislating and legitimating neoliberalism in Mexico, as bitingly summarized by Muñoz Ledo above, there exist few systemic accounts (that is, accounts that move beyond personalist narratives of ‘greed’ and ‘betrayal’) that offer us a comprehensive explanatory framework for the contemporary decomposition of Mexico and the changing structural role of the state and political class within that decomposition. Lacking this systemic account, a number of theorists have turned their attention to the Zapatistas’ break with the Mexican political class and their attempts at building ‘another politics’, and concluded that these amount to nothing more than a sectarian ‘antipolitical’ drift that has led to the ‘failure’ of Zapatista initiatives and to their increasing political irrelevance (Almeyra, 2014; Mondonesi, 2014; Wilson, 2014). It should be noted here that these supposed EZLN shortcomings are often explained in terms of the personal failings (that is, the intransigence, sectarianism, and envy) of its (former) spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos (Almeyra, 2014; Rodriguez Araujo, 2008).

Yet, in sharp contrast to these analyses, after the failure of their initiative on constitutional reforms, the Zapatistas set out on an extensive evaluation of contemporary capitalism that in many ways foresaw the destructive dynamics that today grip Mexico and, increasingly, the rest of the world. In order to examine the Zapatistas’ account of these dynamics, we might first ask what it is that they meant in their 21 December 2012 message that ‘your world’ is ‘crumbling’. Examination of the Zapatistas’ extensive literature on this topic makes evident that for them, the world that is crumbling is that of capitalism. In their description of the crumbling of this world, the Zapatistas ask us to imagine capitalism as a building of sorts. In the past, those on top of this world would add floors to the building—what Marx would have referred to as the expanding ‘self-valorization of value’ (Marx, 1976), or what is often erroneously referred to as ‘growth’. This is a process made possible through the exploitation, dispossession, repression, and disvalorization of those below—what the EZLN refers to as ‘the four wheels of capitalism’ (EZLN, 2013). This allowed those on top to further distinguish themselves, while creating the possibility (however remote) that those below (at least those willing to give in to the social relations of the value form) might move up a floor (most often through redistributive state action).

Today, as the Zapatistas explain, within neoliberal globalization the four wheels of capitalism continue on with a vengeance, but have come unhinged from the capitalist motor that previously drove the construction of new floors (EZLN, 2013). Absent the capacity to build new floors (to rise on the back of the expansion of the self-valorization of value), those on the top of the capitalist world building have little choice but to systematically turn to ‘speculation’ (that is, the attempt to stay on top through profitability minus value expansion) (EZLN, 2014a). According to the Zapatistas, these ‘speculative’ attempts of those at the top to maintain their elevated positions can only come at the cost of the short-sighted and disastrous demolition of the floors and building foundations below them (EZLN, 2013). Consequently, the social relations, territories, and institutions dependent on the expansive dynamic of the self- valorization of value—perhaps most importantly, the state—are completely refunctionalized. From this perspective, political spaces (that is, those spaces between state and civil society), which previously served as sites for mediation, deliberation, and representation, today are reduced to guaranteeing immediate corporate profitability. Lacking the material with which to mediate social conflict (that is, growing self-valorizing value) that in previous eras might have allowed for redistribution and some dialectic of demand and reform, the state now becomes the central machine for demolition, for unilateral dispossession and repression (the cause of the dynamics of ‘exceptionality’ highlighted by Fazio above). Thus, the Zapatistas claim that the era in which capital and the state could uphold even a semblance of peace and stability is over (EZLN, 2014a).

Given this refunctionalization of the state, the problem for Mexico under the “reign of speculation” (that is, neoliberal globalization), according to the Zapatistas, is not “that the political system has links to organized crime, to narcotrafficking, to attacks, aggressions, rapes, beatings, imprisonments, disappearances, and murders”, but rather “that all of this today constitutes its essence” (EZLN, 2014b, no page number). The Italian journalist Roberto Saviano offers a strikingly parallel insight in his 2013 foreword to Anabel Hernández’s Narcoland. Saviano notes that too often the cataclysmic violence that Mexico faces has been minimized and misunderstood by attributing it to a “mafia that has transformed itself into a [transnational] capitalist enterprise”, effectively coopting the Mexican state. For Saviano, however (as well as for the Zapatistas), this perspective entirely misses the point that in the era of speculation “[transnational] capitalism has transformed itself into a mafia”, effectively creating a world in which political economy and criminal economy are but one and the same (Hernández, 2013b, pages viii–x). According to the Zapatistas, then, the problem is not that states have disappeared but rather that they have been entirely remade as nodes of a single global network of contemporary ‘mafia capitalism’ [what the EZLN calls ‘the empire of money’).

I think we must understand three important points that follow from this Zapatista analysis. First, in sharp contrast to the analysis suggested in 2009 by the (now defunct) US Joint Forces Command (Debusmann, 2009), the Zapatistas in no way believe that Mexico is—or is on the verge of becoming—a ‘failed state’. For them Mexico is, rather, a paradigmatic example of a ‘successful’ contemporary capitalist ‘(non)national state’, with all the death, fragmentation, and destruction this entails (EZLN, 2005a). Second, the political class and the institutional left cannot simply stand above the refunctionalization of the state. Rather, if we assume that the left has historically had some relation to the egalitarian but that even the minimally redistributive mechanisms of the state have disappeared, there can by definition be no state- based left today. These positions, which the Zapatistas refer to as “above and to the left”, are simply attempts to enact what for them in today’s world is an “impossible geometry” (EZLN, 2005a, no page number). It would be far more accurate, they claim, to speak of the existence within state politics of a far-right, a right, and a moderate-right, all of which during the electoral cycle fight to appear under the banner of the ‘center’ (EZLN, 2005a). This helps us to understand why it is that (far beyond personal failings) those within the institutional left are constantly reduced to offering themselves as better managers of the very same demolition of the institutions and social relations required by contemporary capital [thus AMLO’s insistence on the need to maintain “macroeconomic equilibrium”] (EZLN, 2005a, no page number). Beyond Mexico, this analysis might also help us to understand how it is that counterhegemonic projects in the rest of Latin America—so admired by the progressive left in Mexico—shifted from the construction of ‘socialism for the 21st century’ only a decade ago to propounding ‘Andean–Amazonian capitalism’ today, or from the idea of building ‘oil sovereignty’ via the ‘Bolivarian Revolution’ to pleading for the securitization of oil debts in the offices of Goldman Sachs (Rathbone and Schipani, 2014; Svampa and Stefanoni, 2007). Third, given the crumbling of the world above, there arises the necessity of rebuilding politics from outside of the state apparatus (what the Zapatistas call ‘another politics’). This necessity rises to the level of an unprecedented urgency given that the destructive and runaway character of contemporary capitalism, as described by the Zapatistas, presents the very real possibility that, as Mexican society can intuit from the experience of the last two decades, the entire building of capitalism itself may collapse, taking the conditions for social and biological life on Planet Earth along with it (EZLN, 2013).

B. The politics of changing worlds

As should be clear by now, the Zapatistas’ post-2001 conjunctural analysis of contemporary capitalism led them to conclude that the world up above was in fact crumbling and that, as they stated, “there is nothing that can be done up there” (EZLN, 2005a). They carefully avoided, however, promoting either some form of paralysis (that is, nothing can be done) or some form of automatism (that is, capitalism will disappear of its own accord). Rather, they insisted that even as the expansion of capitalist valorization was no longer a possibility, without concerted collective action the processes of exploitation, dispossession, repression, and disvalorization could continue indefinitely. Yet, if the Zapatistas believe that a politics ‘above and to the left’ is today an ‘impossible geometry’, the question still remains as to where in the social diagram they think their idea of ‘another politics’ might arise.

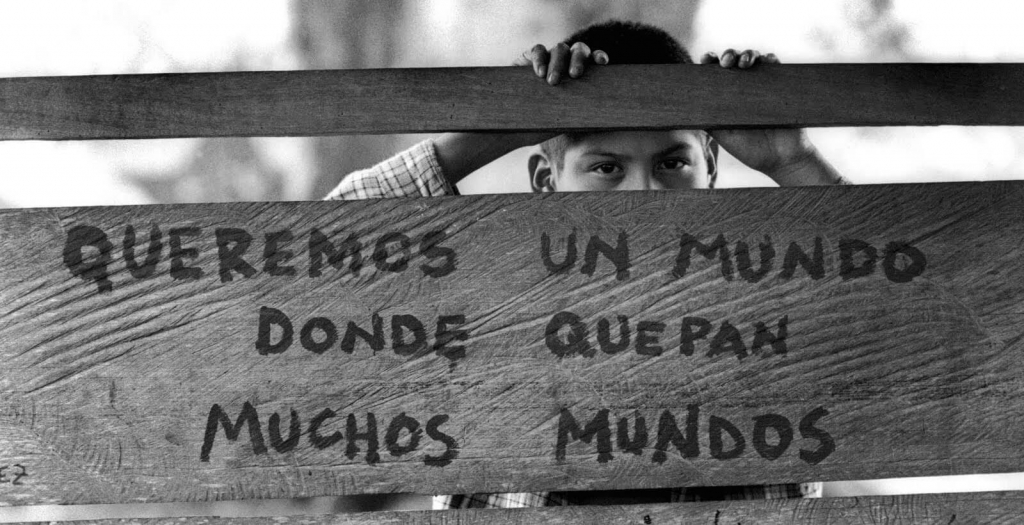

In order to understand the Zapatistas’ answer to this question, we must begin by highlighting their insistence, much like that of Karl Marx in his (1976) ‘idyllic proceedings’, that capitalism was not born of commodity production. Rather, as they state, “capitalism was born of the blood of our [indigenous] peoples and the millions of our brothers and sisters who died during the European invasion” (EZLN, 2014c). From its beginning, then, capitalism was made possible by that ‘dispossession’, ‘plunder’, and ‘invasion’ called ‘the conquest of the Americas’. This attempted conquest, the Zapatistas claim, initiated a ‘war of extermination’ against indigenous peoples that has lasted for more than 520 years, and has been characterized by “massacres, jail, death and more death” (National Indigenous Congress and EZLN, 2014, no page number). Thus, for the Zapatistas, capitalism has always been a two-sided affair: on one side the processes, institutions, and subjects associated with the expansion of the self-valorization of value (that is, the ‘world up above’); and on the other, a foundational and ever-present exceptionality, a permanent state of war, directed at the non-European ‘originary peoples’ of the world. By identifying this ‘global apartheid’ (EZLN, 2013) as the ever-present condition for the production of capitalist value, the Zapatistas are able to see that although firmly within the world of capitalism, not all social subjects are of that world. By recovering this unique structural position (and note that this is not an identity or culture) of the ‘damned of the earth’ (Rodriguez Lascano, 2013) within capitalist modernity, the EZLN is able to further identify that below the network of transnational corporations, armies, and states that comprise the world of capitalist valorization, there exists a web of distinct social relations and structures of value that have been created by the always already walking dead subjects of capitalist modernity. Here, then, the Zapatistas are able to add coordinates to our contemporary ‘political geometry’: there is the dominant world of capitalist valorization ‘up above’, but there are simultaneously many worlds, immanent to the first, down below.

Having identified these new coordinates of above and below, the Zapatistas do not simply throw away the distinction between left and right. According to them, today these dualistic evaluations must be further complexified: everything must be examined within a quadrangular grid consisting simultaneously of left and right as well as above and below. On a conceptual level, this grid allows the Zapatistas to avoid falling into a series of traps latent within these more dualistic frameworks. First, by identifying both sides of the moving contradiction that is capitalism—that of capitalist valorization and that of a genocidal disvalorization—they avoid the trap of furthering the life of the former at the expense of those subject to the latter (that is, they avoid falling into the complicity of those above and to the left with racialized colonial and imperial projects). Second, as the world above crumbles and consequently expels large masses of people from its realm, this perspective opens the horizon of a politics beyond that of the attempted stabilization of that world (that is, the ‘impossible geometry’ of today’s institutional left). Third, the Zapatistas are able to recognize that there are many projects that would simply like to harness these other worlds below in order to gain entrance into the world above (that is, projects that might attempt to draw a bridge between the world below and the one above and to the right). Finally, from this perspective the Zapatistas can resist the temptation of believing that one can simply hide in the worlds below, as if it was possible to forget that the existence of the world above necessitates the destruction of these other worlds. This allows them to recognize as a mere chimera any strategy from below that presents itself as ‘beyond left and right’, thus seeking to jump over the necessity of ending capitalism (strategies that the Zapatistas might very well categorize as ‘below and to the right’).

Given this analysis, the Zapatistas conclude that only a politics ‘below and to the left’ might open the way beyond either apocalyptic despair or social democratic illusion. If for the Zapatistas the counterhegemonic strategy ‘above and to the left’ of ‘changing governments’ has been nullified by the neoliberal onslaught, their new political geometry helps clarify that politics today must be one of ‘changing worlds’ (EZLN, 2013). Concretely, instead of simply presuming the exteriority of the worlds below [as has been the depoliticizing tendency of the US-based academic discourse that goes by the name of ‘the decolonial’, see Rivera Cusicanqui (2012)], the Zapatistas propose that the politics of changing worlds requires the harnessing of the structures of value and social relations that are present below for the construction of organizational forces that would make possible the definitive exteriorization of those worlds from the world of capitalism.

C. Other geographies: the Zapatista construction of new territorialities

On 5 August 2013, a matter of months after the EZLN’s ‘End of the World’ march, I boarded an open-back three-ton truck headed toward Zapatista territory as one of some 7000 students who would attend the Zapatistas’ ‘Little School’ over the next six months. Each student of the Little School was sent to one of the five zones of Zapatista territory and assigned a family and a ‘guardian’ responsible for our care and education. We were then further distributed among the forty autonomous municipalities and finally into the hundreds of Zapatista communities that constitute each of these municipalities. The Little School itself deserves far more analysis and attention than I can provide here; I will limit myself to a very preliminary description of what the Zapatistas shared through this event, with the specific goal of providing elements to better grasp the strategy the EZLN has followed given its analysis of contemporary capitalism as laid out above.

As we arrived at the Little School, each student was handed a packet of four Zapatista textbooks titled Autonomous Government I and II, Women’s Participation, and Autonomous Resistance. These were not a series of directives from organizational leadership, but rather accounts from hundreds of community members from each Zapatista zone explaining their daily experiences of building another politics. These textbooks served not just as primers for students to learn the history of building self-government in each zone, but as an introduction to Zapatista areas of work that we would witness in person: education, healthcare, traditional medicine, and collective productive projects, the latter serving as the primary source of income at a local level. Each day we were methodically introduced to the schools, clinics, women’s collectives, and fields where each of these work areas were carried out, and many students were able to sit in on local assemblies convoked in each community to plan our lessons. We then continued our education with zone-level courses where our Zapatista teachers detailed how each area of work we had witnessed was coordinated between the local communities (commissions), the municipal level (autonomous councils), and the zone (Good Government Councils). Here we also learned about municipal-level communal radio and video projects and, at the most expansive scale, zone-wide agroecological projects and commercial trade. All of this took place, at least in part, on the hundreds of thousands of acres of land recuperated by the EZLN in the 1994 uprising.

Through the Little School, what became apparent even in this brief glimpse into the intricacies of Zapatista autonomous institutional life was that the EZLN had for a long time followed what in the language of traditional Maoism we might call ‘a two- legged strategy’. If the Zapatistas had publicly attempted to help weld together a national counterhegemonic project through the empty signifier of ‘Marcos’ they had also, since the founding of their autonomous municipalities in late 1994, expended enormous energy on the parallel strategy of building ‘dual power’—the creation of a set of institutions that stand as a direct alternative to the existing institutions of the state (Lenin, 1964).(8) It seems that once the EZLN had concluded that the crumbling of the world above had obliterated the already tenuous tie between the counterhegemonic and the antisystemic— thus making the building of a project below and to the left an immediate necessity—its public discursive strategy became superfluous (something that might help explain why, on 25 May 2014, the figure of ‘Marcos’ was officially declared ‘dead’ by the very man behind that figure, now appearing in perfect health under the name of Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano). Hence its previously internal work, now solidified by two decades of experience, was brought to the fore as a concrete existing example of a strategic anticapitalist alternative for the left as whole.

Yet, even the Leninist concept of ‘dual power’ or the parallel Maoist strategy of ‘building red bases’ ultimately proves inadequate to describe the Zapatista strategy. Both these ideas leave open the possibility that, even as their alternative institutions build mechanisms for the contestation of power, they depend on (and ultimately seek) the same single social substance of power as that of the state. In other words, from the ambivalence inherent in these concepts it might appear that the Zapatistas have attempted to construct a demarcated subterritory “within the territorial logic of power commanded by the Mexican state” (Harvey, 2010, page 252). However, from the Zapatista’s perspective, ‘the territorial logic’ of the Mexican state (the territory of the Mexican nation-state) no longer exists as such. The EZLN is acutely aware that in the latest wave of reterritorialization, Mexico’s formerly ‘national’ territory (like its spaces of institutional mediation) has been fragmented into hundreds of pieces, each subordinated to the needs of multinational corporations, drug cartels, and local political mafias (that is, the needs of contemporary capitalism). This is the territorial consequence of the formation of what the Zapatistas refer to as a capitalist “non-nation state” (EZLN, 2005a), reflecting a process of fragmentation that is in their eyes irreversible.

Furthermore, for the Zapatistas, the entire purpose of the respatialization of struggle that we witnessed as students of the Little School—what they refer to as the construction of ‘another geography’—is to break (with) the logic of power of the state. As they say, “we think if we conceptualize a change in the premise of power, the problem of power, starting from the fact that we don’t want to take it, that could produce another kind of politics and another kind of political actor, other human beings that do politics differently than the politicians we have today across the political spectrum” (EZLN, 1997, page 69).

In the Zapatista project, then, ‘territory’ does not refer to the relations of a preexisting given subject to a given demarcated spatial extension as is imagined in the dominant conceptions of state territory (Brighenti, 2010). Rather, the Zapatistas take on the construction of new communities, municipalities, and zones—and the nonstate forms of government associated with each—as mechanisms for the production of this new subject of politics. In this practice, territory is not some “neutral carrier” of a single substance of power, but rather “the material inscription of social relations” that can be radically transformed in order to create another power (Brighenti, 2010, page 57). We might best characterize the Zapatista strategy, then, as the construction of another structure of relation between a newly produced collective subject and space—a new ‘territoriality’ (Raffestin and Butler, 2012). This allows the Zapatistas to grow their idea and practice of territory quite literally side-by-side (in the same communities) with the overlapping and contradictory territories of neoliberal calculation and destruction. From this perspective we can understand why it is that the Zapatistas see their territory not as a lever with which to enter this world, but rather as a strategy in the here and now to exit it.

Finally, as Alain Badiou (2008) has noted, the affirmative project of Zapatismo (theorized here as the building ‘other geographies’ that will sustain the new political subject) has allowed the Zapatistas to avoid imagining the process of exiting this world as a civil war—a violent and cataclysmic clash between worlds. Given their affirmative project, the military elements of Zapatismo have been steadily subordinated to the role of defending their political innovations. The importance of this shift should not be underestimated when, given the disappearance of its mediational capacity, the state seems to want nothing more than the militarization of political conflict, a medium it understands and easily dominates.

Conclusion: create two, three, many other geographies

As the decomposition of the world above reaches new heights, and far from the cameras that previously fixated on ‘Marcos’, the Zapatistas’ strategy of building ‘other geographies’ has grown in influence—from the construction of the autonomous municipalities of Cherán and Santa María de Ostula (Michoacan) to the reconsolidation of Mexico’s National Indigenous Congress; from the recent declaration of twenty-two autonomous municipalities in the state of Guerrero to the explicitly Zapatista-inspired ‘democratic confederalism’ of today’s Kurdish movement.

It is important to note that, despite the inspirational perseverance of the EZLN, the long-term temporal framework implicit in the Zapatistas’ current political strategy renders unwarranted any conclusions about its ultimate success or failure. Yet the EZLN has undeniably added strategic coordinates to our contemporary ‘political geometry’, offering a distinct path to a global left that has tended to oscillate wildly and with little success between counterhegemony (verticalization) and spontaneity (horizontalism) in its effort to ‘change governments’. That is, our era has been marked on the one hand by the counterhegemonic strategies of either rebuilding sovereignty over the national territory or working within the ‘nonspaces’ of transnational capital, and on the other hand by the spontaneist practices of protest, occupation, and the establishment of temporary autonomous zones. But in none of these left-wing strategies does the possibility of an innovative territorial production actually appear, as all are ultimately attempts to occupy, reproduce, or at best redistribute the given territory. If, as Claude Raffestin claims, “the production of territories by means of territories is the operation of the creation and recreation of values” (Raffestin and Butler, 2012, page 131), how is it then that through the acceptance of the given territory these strategies will somehow overcome the values of capitalism? It is in this context that the singular contribution of the Zapatistas’ efforts might best be appreciated. For them, it is only through the long and arduous process of enacting the explicitly antiseparatist yet simultaneously territorial strategy of building other geographies that a rather different left might today ‘change worlds’, abandoning capitalist value and in effect ‘ending this world’. Although some within the left (in Mexico and globally) will find the Zapatistas’ strategy an uncomfortable impediment to their counterhegemonic aspirations, and others may sincerely disagree with their analysis, it behooves no one to do so by simply wishing them dead. We must instead open the discussion, as they clearly have, of what it actually means to be on the left today.

Endnotes

(1) For leaked excerpts of the counterinsurgency plan against the EZLN in 1994, see Carlos Marin (1998).

(2) XENK Radio 620, “Política de Banqueta”, Transcription here: http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/ 2006/07/05/radio-insurgente-en-el-df-donde-se-da-informacion-sobre-las-elecciones-del-2-de-julio/

(3) For just one first-hand account of the thesis of the EZLN’s disappearance within Mexico’s ‘progressive’ intellectual circles, see Raul Zibechi (2012).

(4) Even the Anglophone academic world was not untouched by the perception of the EZLN as a spent force. Take, for example, the widely circulated words of David Harvey, who, even half a decade after the Zapatistas’ break with the Mexican political class, concluded (with thinly veiled disappointment) that the Zapatistas had given up on political revolution and instead decided to “remain a movement within the state” (2010, page 252).

(5) For a good summary of Article 27’s provisions for the protection of common land tenure, see Ana de Ita (2006, page 149).

(6) The most important of these programs was PROCEDE (Certification Program for Ejidal Rights and Titling of Parcels). For an analysis of PROCEDE and its relation to the evisceration of Article 27, see de Ita (2006).

(7) For a similar argument regarding Article 27 of the Mexican constitution, see Gareth Williams (2011, pages158–165).

(8) For a more detailed description of the Zapatista’s alternative institutions, see Reyes and Kaufman (2012).

References

Agamben G, 2005 The State of Exception (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL) Almeyra G, 2014, “EZLN: posible escenarios” La Jornada 8 June, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/06/08/opinion/019a1pol

Álvarez L, 2012 Corazón Indígena: Lucha y Esperanza de los Pueblos Originarios de México (Fondo de Cultura Economica, Mexico City)

Arsenault C, 2011, “Zapatistas: the war with no breath?” Al Jazeera 1 January, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2011/01/20111183946608868.html

Badiou A, 2008, “We need a popular discipline: contemporary politics and the crisis of the negative”Critical Inquiry 34 645–659

Bessi R, Navarro S, 2014 “Communal lands: Theater of operations for the counterinsurgency” Truthout 11August, http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/25444-communal-lands-theater-of-operations-for-the- counterinsurgency

Brighenti A M, 2010, “On territorology: towards a general science of territory” Theory, Culture and Society 27 52–72

Brighenti A M, 2013, “From the series: `New social conflict. Extractivism and politics of the common in Latin America’. Interview with Raquel Gutiérrez (Lobo Suelto!)” Making Worlds 18 November, http://www.makingworlds.org/from-the-series-new-social-conflict-extractivism-and- politics-of-the-common-in-latin-america-interview-with-raquel-gutierrez-lobo-suelto/>

Castellanos L, 2008 Corte de Caja: Entrevista al Subcomandante Marcos (Grupo Editorial Endira, Mexico City) Crowley M, Mascareñas D, 2014, “The committee to save Mexico” Time 183 page 34

Debusmann B, 2009, “Among top U.S. fears: a failed Mexican state” The New York Times 9 January,http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/09/world/americas/ 09iht-letter.1.19217792.html?_r=0

de Ita A, 2006, “Land concentration in Mexico after PROCEDE”, in Promised Land: Competing Vision of Agrarian Reform Eds P Rosset, R Patel, M Courville (First Books, Oakland, CA)

Díaz-Polanco H, 2012 La Cocina del Diablo: El Fraude De 2006 y los Intelectuales (Temas de Hoy, Mexico City)

Eichert B, Rowley R, Sandberg S, (Dir), 1999 Zapatista (Big Noise Films)

EZLN, Zapatista Army of National Liberation, Chiapas, Mexico 1997 Crónicas Intergalácticas: Primer Encuentro Intercontinental por la Humanidad y contra el Neoloberalismo (Montañas del Sureste Mexico, Planeta Tierra)

2001 [1994], “First declaration of the Lacandón jungle”, in Our Word is Our Weapon: Selected Writings of Subcomandante Insurgent Marcos (Seven Stories Press, New York) pp 13–16

2005a, “La (imposible) ¿geometría? del Poder en México” Cartas y Comunicados del EZLN June, http://palabra.ezln.org.mx

2005b, “Carta a la Sociedad Civil Nacional E Internacional” Cartas y Comunicados del EZLN 21 June, http://palabra.ezln.org.mx/

2005c, “La Sexta Declaración de la Selva Lacandona” Enlace Zapatista http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/sdsl-es/

2012a, “¿Escucharon?” Enlace Zapatista 21 December, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org. mx/2012/12/21/comunicado-del-comite-clandestino-revolucionario-indigena-comandancia-general- del-ejercito-zapatista-de-liberacion-nacional-del-21-de-diciembre-del-2012/

2012b, “EZLN Announces the Following Steps” Enlace Zapatista 30 December, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/01/02/ezln-announces-the-following-steps-communique-of- december-30-2012/

2013, “Them and us, part V—The Sixth” Enlace Zapatista 27 January, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/01/27/them-and-us-v-the-sixth/

2014a, “Between light and shadow” Enlace Zapatista 25 May, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2014/05/27/between-light-and-shadow/

2014b, “Words of the CG-EZLN to Ayotzinapa Caravan” Enlace Zapatista 14 November, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2014/11/17/the-words-of-the-general-command-of-the-ezln- presented-by-subcomandante-insurgente-moises-concluding-the-event-with-the-caravan-of-the- families-of-the-disappeared-and-students-of-ayotzinapa-in-the/

2014c, “1a Declaracion de la Comparticion CNI-EZLN. Sobre la Represión a Nuestros Pueblos” Enlace Zapatisa 16 August, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2014/08/16/1a-declaracion-de-la-comparticion-cni-ezln-sobre-la- represion-a-nuestros-pueblos/

Fazio C, 2013 Terrorismo Mediático: La Construcción Social del Miedo en México (Random House Mondadori, Mexico City)

Gibler J, 2015, “The disappeared” California Sunday Magazine 4 January, https://stories.californiasunday.com/2015-01-04/mexico-the-disappeared-en

Gilly A, Gutierrez Aguilar R, Roux R, 2006, “América Latina: mutación epocal y mundos de la vida”, in Neoliberalismo y Sectores Dominantes: Tendencias Globales y Experiencias Nacionales Eds E M Basualdo, E Arceo (CLACSO, Buenos Aires) pp 103–119

Gutierrez Aguilar R, 2005, “Reflexión sobre las perspectivas de la emancipación social a partir de los levantamientos y movilizaciones en México y Bolivia” Rebelión 22 October,http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=21627

Harvey D, 2010 The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism (Oxford University Press, New York)

Hernández A, 2013a Mexico en Llamas: El Legado de Calderón (Random House Mondadori, Mexico City)

Hernández A, 2013b Narcoland: The Mexican Drug Lords and Their Godfathers (Verso, London) Hernández Navarro L, 2013, “Zapatistmo: veinte años después” La Jornada 24 December, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2013/12/24/opinion/024a1pol

Laclau E, 1996 Emancipations (Verso, London)

Lenin V, 1964, “On dual power”, in Lenin: Collected Works, Volume 24 (Progress Publishers, Moscow) pp 38-41

López y Rivas G, 2014, “¿Paramilitares?” La Jornada 14 February, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/02/14/opinion/021a1pol

Marín C, 1998, “Plan del Ejército en Chiapas, desde 1994: crear bandas paramilitares, desplazar a la población, destruir las bases de apoyo del EZLN …” Proceso 4 January, pages 6–11

Marx K, 1976 Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1 (Penguin Classics, New York) Modonesi M, 2014, “Postzapatismo: identidades y culturas juveniles y universitarias en México” Nueva Sociedad May 251 136–152

National Indigenous Congress and EZLN, 2014, “Segunda declaración de la compartición CNI- EZLN: sobre el despojo a nuestros pueblos” Enlace Zapatista 16 August, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2014/08/16/2a-declaracion-de-la-comparticion-cni-ezln-sobre-el- despojo-a-nuestros-pueblos/

Negri A, 1994, “Labor in the constitution”, in Labor of Dionysus: A Critique of the State-form Eds M Hardt, A Negri (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN) pp 53-138

Petrich B, 2011, “EU no veía mal la llegada de López Obrador a Los Pinos” La Jornada 5 April,http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2011/04/05/politica/002n1pol

Rabasa J, 2007, “Of Zapatismo: Reflections on the folkloric and the impossible in a subaltern insurrection,” in The Politics of Culture In the Shadow of Capital Eds L Lowe, D Lloyd (Duke University Press, Durham, NC)

Raffestin C, Butler S A, 2012, “Space, territory, and territoriality” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30 121—141

Rathbone J P, Schipani A, 2014, “Venezuela’s new best friend—Goldman Sachs” Financial Times3 December, http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2014/12/03/ venezuelas-new-best-friend-goldman-sachs/

Reyes A, 2012, “Revolutions in the revolutions: a post-counterhegemonic moment for Latin America?” The South Atlantic Quarterly 111(2) 1–27

Reyes A, Kaufman M, 2011, “Zapatista autonomy and the new practices of decolonization” The South Atlantic Quarterly 110(2) 505–525

Rivera Cusicanqui S, 2012, “Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A reflection on the practices and discourses of decolonization” South Atlantic Quarterly 111(1) 95–109

Rodriguez Araujo O, 2006, “AMLO and Marcos” La Jornada 21 September, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2006/09/21/index.php?section=opinion&article=027a1pol

Rodriguez Araujo O, 2008, “El fin del liderzgo del Subcomandante Marcos” Casa del Tiempo 2 December 2008–January 2009, http://www.uam.mx/difusion/ casadeltiempo/14_15_iv_dic_ene_2009/

Rodriguez Lascano S, 2013, “Carta a nuestr@s compañer@s del Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional” Enlace Zapatista 20 December, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/12/20/carta-a- nuestrs-companers-del-ejercito-zapatista-de-liberacion-nacional/

Schmitt C, 2003 The Nomos of the Earth: In the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europium (Telos Press, New York)

Svampa M, Stefanoni P, 2007, “Entrevista a Álvaro García Linera: ‘Evo simboliza el quiebre de un imaginario restringido a la subalternidad de los indígenas’” OSAL 8 143–164

Villamil J, 2013, “El sistema cambió, mas no para bien” Proceso 21 32–34

Watt P, Zepeda R, 2012 Drug War Mexico: Politics, Neoliberalism and Violence in the New Narcoeconomy (Zed Books, New York)

Williams G, 2011 The Mexican Exception: Sovereignty, Police, and Democracy (Palgrave MacMillan, New York)

Wilson J, 2014, “The violence of abstract space: contested regional developments in southern Mexico” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 515–538

World Bank 2001, “Mexico: land policy—a decade after the Ejido Reform”, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/ handle/10986/15460

Wright M W, 2011, “National security vs. public safety: femicide, drug wars, and the Mexican state”, in Accumulating Insecurity: Violence and Dispossession In the Making of Everyday Life Eds S Feldman, C Geisler, G Mennon (University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA) pp 285–297

Zibechi R, 2012, “Eco mundial en apoyo de l@s zapatistas: carta de Raúl Zibechi, un nuevo nacimiento” Enlace Zapatista 13 November, http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2012/11/13/eco- mundial-en-apoyo-de-ls-zapatistas-carta-de-raul-zibechi-un-nuevo-nacimiento/