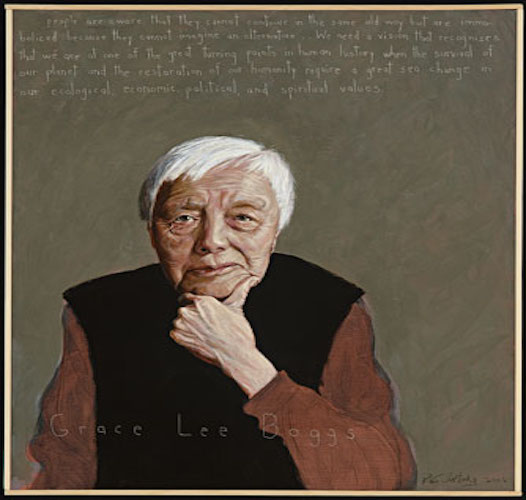

Grace Lee Boggs – Education: The Great Obsession

This essay was originally published in the September 1970 issue of Monthly Review. Education today is a great obsession. It is also a great necessity. We, all of us, […]

Read moreThis essay was originally published in the September 1970 issue of Monthly Review. Education today is a great obsession. It is also a great necessity. We, all of us, […]

Read more

– James Boggs: The American Revolution

– Grace Lee Boggs: Introduction to Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century

– Grace Lee Boggs – Education: The Great Obsession

– James Boggs: Think Dialectically, Not Biologically

– James Boggs: Towards a New Concept of Citizenship

– Grace Lee Boggs: Naming the Enemy

This essay was originally published in James Boggs’ The American Revolution: Pages from a negro worker’s notebook Any social movement starts with the aim of achieving some rights heretofore denied. […]

Read moreOriginally published on New Compass. The following speech was delivered at the “Challenging Capitalist Modernity: Alternative concepts and the Kurdish Question” conference which took place in Hamburg, Germany over February 3-5, […]

Read moreThis Lecture was presented by the American Academy in Berlin. “The current crisis has laid bare the contradictory and shaky character of contemporary capitalism. Yet the essentially inchoate responses to […]

Read moreOriginalmente publicado en La Voz del Interior. No muchas personas se enteraron, pero la semana pasada estuvo en Córdoba uno de los filósofos anticapitalistas más críticos y radicales del pensamiento […]

Read more“The happiness that dawns in the eye of the thinking person is the happiness of humanity. The universal tendency of oppression is opposed to thought as such. Thought is happiness, […]

Read more

– Janet Biehl: Bookchin, Öcalan, and the Dialectics of Democracy

– Maurizio Lazzarato: “El capitalismo no necesita de la democracia”

– Theodor W. Adorno: Resignation

– Moishe Postone: Capitalism, Temporality and the Crisis of Labor

– Damian Carrington: Arctic Stronghold of the World’s Seeds Flooded After Permafrost Melts

This article was originally published on May 19, 2017 in The Guardian. It was designed as an impregnable deep-freeze to protect the world’s most precious seeds from any global disaster […]

Read moreThis article was originally published on Unsettling America. There is a significant and to my mind problematic limitation that is increasingly being placed on Indigenous efforts to defend our rights […]

Read more