Grace Lee Boggs: Introduction to Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century

This essay was originally published in a new printing of Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century.

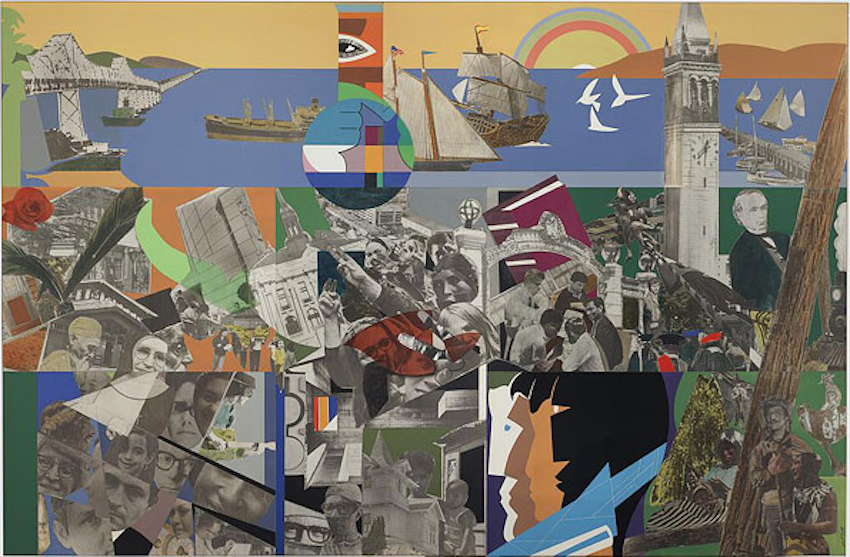

Romare Bearden. The City and its People. 1973

I feel blessed that at ninety-three I am still around to tell a new generation of movement activists the story of why James and I wrote Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century (RETC) in the early 1970s, and why I welcome its present republication by Monthly Review Press with its original contents and a new title: Revolution and Evolution in the Twenty-first Century.

James died in July 1993. We had been partners in struggle for forty years. He and his way of looking at the world are still very much with me. But the world and I have changed a lot in the last fifteen years as I have continued our struggle to change the world. i

RETC (as I will refer to the 1974 publication) is an example of the critical role that continuing reflection on practice and practice based on reflection need to play in the lives of movement activists.

In the late 1960s, in the wake of the urban rebellions and the explosive growth of the Black Panther Party, both before and after Dr. King’s assassination, Jimmy and I decided that after our intense involvement in the Black Power movement, we and the American movement needed a period of reflection. This would enable us to figure out where we were and where we needed to go in order to transform the United States into the kind of country that every American, regardless of race, class, ethnicity, or national origin, would be proud to call our own.

So in June 1968 we got together with our old comrades, Lyman and Freddy Paine, on a little island in Maine to begin the annual conversations that continue to this day. ii

The first outcome of these conversations was our recognition that the ongoing rebellions were not a revolution, as they were being called by many in the black community and by radicals and liberals. Nor were they only a breakdown in law and order or a riot, as they were labeled in the mainstream media. A rebellion, we decided, is an important stage in the development of revolution because it represents the massive uprising and protest of the oppressed. Therefore it not only begets reforms but also throws into question the legitimacy and supposed permanence of existing institutions.

However, a rebellion usually lasts only a few days. After it ends, the rebels are elated. But they then begin to view themselves mainly as victims and expect those in power to assume responsibility for changing the system. By contrast, a revolution requires that a people go beyond struggling against oppressive institutions and beyond victim thinking. A revolution involves making an evolutionary/revolutionary leap towards becoming more socially responsible and more self-critical human beings. In order to transform the world, we must transform ourselves.

Thus, unlike rebellions, which are here today and gone tomorrow, revolutions require a patient and protracted process that transforms and empowers us as individuals as we struggle to change the world around us. Going beyond rejections to projections, revolutions advance our continuing evolution as human beings because we are practicing new, more socially responsible and loving relationships to one another and to the earth.

In the process of arriving at this evolutionary humanist concept of revolution, it became clear to us that Marx’s revolutionary scenario (which so many generations of radicals, including ourselves, had embraced) represented the end of an historical epoch, not the beginning of a new one. Writing over one hundred years ago, in the springtime of the industrial revolution and an epoch of scarcity, Marx viewed the rapid development of the productive forces and the more just and equal distribution of material abundance as the main purpose of revolution. In a period when industrial workers were growing in numbers, it was natural for him to view the working class, which was being disciplined, organized, and socialized by the process of capitalist production, as the social force that would make this revolution.

Since then, however, under the impact of the technological revolution, especially in the United States, the working class has been shrinking rather than growing. At the same time the material abundance produced by rapid economic development has turned the American people, including workers, into mindless and irresponsible consumers, unable to distinguish between our needs and our wants. Moreover, we, the American people, have been profoundly damaged by a culture that for over two hundred years has systematically pursued economic development at the expense of communities, and of millions of people at home and abroad. Our challenge is to continue the evolution of human race by grappling with the contradiction between our technological and economic overdevelopment and our human and political underdevelopment. iii

Armed with this new, evolutionary humanist concept of revolution, we presented the Manifesto for a Black Revolutionary Party at the National Black Economic Development Conference meeting in Detroit in 1969, urging Black Power activists to recognize that blacks have been in the forefront of revolutionary struggles in the United States down through the years because their struggles have not been for economic development but for more human relationships between people.

The next year we gave a series of lectures “On Revolution” at the University Center for Adult Education in Detroit. We began by pointing out that, although Lenin and the Bolsheviks had been able to seize state power in 1917, they were unable, in power, to involve the workers and peasants in governing the Soviet Union because their “revolution” had been an insurrection or event rather than a protracted process involving empowerment and transformation. Fortunately, however, the leaders of subsequent revolutions in China, Vietnam and Guinea Bissau learned from the Russian experience, and struggled valiantly to make transformation, serving the people and self-criticism an integral part of the struggle for power, in the process enriching the concept of revolution.

Thus the historical development of revolutions during the twentieth century has been a dialectical process in the course of which revolutionary leaders have been constantly challenged by the contradictions created by earlier revolutions to keep deepening the theory and practice of revolution.

Our challenge as American revolutionaries is to carry on this legacy, always bearing in mind that, unlike Russia in the early twentieth century and China, Vietnam and Guinea-Bissau in later decades, our country has already undergone a century of rapid industrialization and is in the midst of a technological revolution whose political and cultural implications are as far-reaching as those of the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture eleven thousand years ago and from agriculture to industry three hundred years ago. Our challenge, as we say at the end of the chapter on “Dialectics and Revolution” in RETC, is to recognize that the crises facing our economically overdeveloped society can only be resolved by a tremendous transformation of ourselves and our relationships to each other and to the rest of the world.

Only a few dozen people participated in the ”On Revolution” series. But the process was so inspiring that we decided to use the materials as the basis for forming revolutionary study groups. So in Detroit and a few other cities we began to bring together black activists with whom we had worked during the 1960s. At the same time we arranged with Monthly Review Press to publish the series as Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century. iv

By the time RETC came off the press in 1974 we had formed revolutionary study groups of black activists in Detroit, Philadelphia, New York City and Muskegon, Michigan, some of whom went on to form local organizations. These groups were small because most blacks were taking advantage of the mushrooming opportunities for upward mobility that had been created by the rebellions. v Thousands of people bought copies of the Manifesto for a Black Revolutionary Party and carried them around conspicuously in their dashiki pockets. But only a handful were willing to commit the time and energy necessary to begin thinking about revolution in a more evolutionary way. vi

In the early 1970s these study groups did not include whites because our focus was on developing black leadership for the American revolution. However, after blacks joined the coalition that elected Jimmy Carter president in 1976, we decided that, like labor and women, blacks had become a self-interest group. Therefore the period in which an American revolution might have been made under black revolutionary leadership had come to an end. The time had come to develop members of the many ethnic groups who make up our country so that together we could give leadership in the protracted and many-sided struggles needed to revolutionize the United States. vii

By the 1980s, through a carefully thought-out program for what we called national expansion, new, mostly white, locals had been founded in Milwaukee, Seattle, Portland, Oregon, Syracuse, Boston and the Bay Area, and had joined with the mostly black locals in Detroit, Philadelphia, New York, Muskegon, Newark, New Jersey, and Lexington, Kentucky, to form the National Organization for an American Revolution (NOAR). Each new local created its own founding document from a study of the city for which it was assuming responsibility.

Except for Detroit and Philadelphia, most locals consisted of only a half-dozen or even fewer members. But our output was prodigious, mainly because of the sense of empowerment that had come from the study of RETC. Each member felt called upon to go beyond protest and rebelling, and embrace and inspire in others the conviction that we have the power within us to create ourselves and the world anew.

To demystify leadership, we decentralized responsibility for writing and publishing pamphlets that explored the new concepts and institutions needed for our rapidly changing reality.

Thus Philadelphia assumed responsibility for publishing five printings of the Manifesto for a Black Revolutionary Party. Detroiter Kenny Snodgrass, barely out of his teens, wrote the introduction to The Awesome Responsibilities of Revolutionary Leadership. The tiny Muskegon local wrote and published two pamphlets, one entitled A New Outlook on Health and the other, Women and the New World. The New York local wrote and published Beyond Welfare. Syracuse produced Going Fishing, a statement on the local environment. Seattle published A Crisis of Values and A Way of Faith, A Time for Courage, based on a talk on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by Rosemary and Vincent Harding. Detroit produced Crime Among Our People (five printings). Education to Govern (three printings). But What About the Workers? What Value Shall We Place on Ourselves? Women and the Movement to Build a New America. Towards a New Concept of Citizenship. Manifesto for an American Revolutionary Party (English and Spanish). Look! A Nation is Coming! Native Americans and the Second American Revolution.

In our internal development programs we studied American history and gained an appreciation and love for our country as a work in progress, constantly challenged by those excluded from its promise and by the contradictions of capitalism to keep deepening the concept of citizenship and what it means to be an American. While most radicals rejected this approach as “American exceptionalism,” we welcomed the uniqueness of our history as the key to the American revolution. viii

We explored what it means to think dialectically and to go beyond the scientific rationalism of Descartes. In propaganda workshops we analyzed the significance of the spoken and written word, and practiced writing preambles for community organizations, using the Preamble to the U. S. Constitution as a model.

We tried to create an alternative to charismatic leadership and a balance between activism and reflection. At annual conventions every member participated equally in evaluating the previous year’s work and in deciding the direction and structures for the next year. Our continuing conversations in Maine and in Detroit provided opportunities for the reflection necessary to give deeper meaning to our activism. ix

We were proud of our self-reliance. With no paid staff we had no need for grants or outside funding. Instead each local sustained itself by membership dues and literature sales.

Meanwhile, profound changes were taking place in the United States and the world because of new developments in transportation and communications. The fragmentation of the production process into a host of component operations was making it easy for corporations to abandon U.S. plants and cities and move to other parts of the country or the world where they could make greater profits with cheaper labor and fewer social or environmental regulations. Corporations were abandoning cities, and blackmailing city governments by demanding tax abatements and other concessions, making it increasingly difficult for municipalities to supply normal services.

To understand these developments and the changes they required in our thinking and our practice, in 1982 we published the Manifesto for an American Revolutionary Party in which we warned that capitalism had entered a new stage, the stage of multinational capitalism, which was even more destructive than finance and monopoly capitalism because it threatened our communities and our cities: Up to now, most Americans have been able to evade facing the destructiveness of capitalist expansion because it was primarily other peoples, other cultures which were being destroyed…. But now the chickens have come home to roost. While we were collaborating with capitalism by accepting its dehumanizing values, capitalism itself was moving to a new stage, the stage of multinational capitalism…. Multinational corporations have no loyalty to the United States or to any American community. They have no commitment to the reforms that Americans have won through hard struggle…. Whole cities have been turned into wastelands by corporate takeovers and runaway corporations….

That is why as a people and as a nation, we must now make a second American revolution to rid ourselves of the capitalist values and institutions which have brought us to this state of powerlessness – or suffer the same mutilation, the same destruction of our families and our communities, the same loss of national independence as over the years we have visited upon other peoples and cultures.

To move towards this goal we need a new vision of a self-governing America based on local self-government, strong families and communities, and decentralized economies. Therefore revolutionary leadership will:

project and assist in the organization of all types of community committees: Committees for Crime Prevention that will establish and enforce elementary standards of conduct, such as mutual compacts not to buy ‘hot goods,’ Committees to Take Over Abandoned Houses for the use of community residents who will maintain them in accordance with standards set by the community; Committees of Family Circles to strengthen and support parents in the raising of children; Committees to Take Over Neighborhood Schools that are failing to educate our children or to take over closed down schools so as to provide continuing education for our children; Committees to Resist Utility Cutoffs by companies which, under the guise of public service, are in reality private corporations seeking higher profits to pay higher dividends to their stockholders; Committees to Take over Closed Plants for the production of necessary goods and services and for the training and employment of young people in the community; Anti-Violence Committees to counter-act the growing resort to violence in our daily relationships; Committees to Ban All Nuclear Weapons that will rally Americans against the nuclear arms race as the anti-war movement rallied Americans against the Vietnam war in the early 1970s.

These grassroots organizations can become a force to confront the capitalist enemy only if those involved in their creation are also encouraged and assisted by the American revolutionary party to struggle against the capitalist values which have made us enemies to one another. For example, in order to isolate the criminals in our communities, we must also confront the individualism and self- centredness which permits us to look the other way when a neighbor’s house is being robbed.

The publication of the Manifesto for an American Revolutionary Party energized the organization. Talking about our country and our communities, working together to develop ideas and programs for building communities, listening to the stories of everyone’s lives and hopes, comrades discovered a new patriotism, a deeper rootedness and sense of place both in their communities and in the nation.

This enlarged sense of ourselves was unmistakable at the second NOAR convention in 1982. It came across especially in the poem “We Are the Children of Martin and Malcolm,” written by Polish American John Gruchala, African American Ilaseo Lewis, and myself for the June 1982 Great Peace March in New York, and read by John and Ilaseo at the convention:

We are the children of Martin and Malcolm Black, brown, red and white

And so we cannot be silent

As our youth stand on street corners and the promises of the 20th century pass them by.

We are the children of Martin and Malcolm

Our ancestors.

Proud and Brave

Defied the storms and power of masters and madmen.

We are the children of Martin and Malcolm.

So when money-eyed men remove the earth beneath our feet and bulldoze communities,

And Pentagon generals assemble weapons to blister our souls and incinerate our planet, We cannot be silent.

We are the children of Martin and Malcolm.

Our birthright is to be creators of history,

Our glory is to struggle,

You shall know our names as you know theirs, Sojourner and Douglass, John Brown and Garrison.

We are the children of Martin and Malcolm, Black, brown, red and white,

Our Right, our Duty

To shake the world with a new dream.

It was a very moving convention. We felt that together, African American, European American, Asian American, female and male, gay and straight, we were beginning to create a more perfect union and carrying on the American revolutionary tradition of Sojourner and Douglass, John Brown and Garrison, Martin and Malcolm.

Inspired by the ideas in the Manifesto for an American Revolutionary Party, members of the Detroit local began organizing in the community. Some members organized the Michigan Committee to Organize the Unemployed (MCOU) and began a struggle to obtain continuing health insurance for laid-off workers. Others organized Committees to Resist Utility Cutoffs. After MCOU failed to rally laid-off workers, comrades began helping residents in the Marlborough neighborhood, where MCOU had been holding street corner meetings, to close down crack houses.

After Reagan and Bush won the 1980 election, we called on all Americans to “Love America enough to change it.“ “Our Communities and our Country are now up to us!” During Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaign in 1984 we distributed leaflets challenging both white and black Americans to seize the opportunity to create a new movement. “We can’t leave it all to Jesse!”

In 1984 we also joined the “cheese line,” which during the Reagan years provided millions of Americans with basic commodities. On the “cheese line” in Detroit we discovered that the elderly and disabled were being trampled on by the young and able-bodied. So we organized them into a group calling itself Detroiters for Dignity and waged a successful campaign for an extra distribution day for elders. Detroiters for Dignity brought an elders’ conscience to the struggle in our city. We wrote letters to the editor, organized and attended community meetings, hosted meetings against the military involvement in Central America, and in 1985 drove to Big Mountain in Arizona to support the resistance of the Dineh (Navajo) people to their forced relocation.

Then, suddenly, despite or perhaps because of all this external activity, NOAR began falling apart. Differences that had been viewed as enriching became sources of tensions. Members began resigning, citing personal concerns (family, jobs) that demanded their time and energy. But political questions, even if unspoken, were also at issue. For one thing, members had committed themselves to build an organization with people who shared their views. Going out into the community to try to build a movement from scratch required a different kind of commitment and preparation. Also, despite our efforts to decentralize and demystify leadership, we had not deconstructed Marxist-Leninist concepts of democratic centralism and the vanguard party. Organizations in the black community especially need to accept this challenge because it is too easy for them to adopt the topdown and male leadership patterns of the black church.

Another troubling undercurrent was the decision the organization had made to go beyond projecting black leadership of the American revolution. Theoretically it was clear that the black movement as a movement was dead, but for black comrades the concept of black leadership for the American revolution had been a very heady one and giving it up felt a lot like betrayal.

We never formally dissolved NOAR. Between 1985 and 1987 it just faded away as members resigned or became so much involved in community activities that they had no time for our meetings. Our total membership was never more than seventy-five to a hundred. But between 1970, when we first began organizing on the basis of the ideas in the Manifesto for a Black Revolutionary Party, and 1985, when NOAR ran out of steam, these few comrades were incredibly creative.

The audacity of Jimmy’s challenge to blacks to stop thinking like a minority and assume leadership for an American revolution had lifted black comrades beyond victim or minority thinking (Jimmy called it “thinking like an underling”) and empowered them to use their anger in a positive way, uncovering talents and energies that otherwise might have been wasted.

Our emphasis on the contradiction between economic and technological overdevelopment and political and human underdevelopment enabled us to explore a wide range of social, political, cultural, and artistic questions and to tackle questions of crime and welfare with proposals and positive programs for building social responsibility, community and citizenship. As a result, we attracted people with imagination and artistic sensibilities from all walks of life. Between 1974 and 1984 few joined us as members, but thousands read our literature and hundreds attended our meetings.

Overall anyone who was a NOAR comrade or was exposed to its ideas felt that our humanity had been enlarged by the challenge to go beyond rebellion to revolution, beyond victim thinking, and beyond our personal grievances and identity struggles to assuming responsibility for a new concept of citizenship and of a self- governing America. Almost everyone has continued some form of activism.

In retrospect, I think that the main reason for NOAR’s demise is that it had outlived its usefulness and the time had come to let it go out of existence. That is one of the many important lessons I learned from the experience. Even though we went through various stages with different names, we had essentially come out of the rebellions of the late 1960s. Our goal had been to do what the Black Panther Party had been unable to do: develop evolutionary/revolutionary ideas and a new kind of leadership for the exploding black movement. When that movement came to an end, we kept trying to adapt ourselves to the changing situation. It is no accident that our internal development programs and our publications, which boldly explored visionary solutions for our rapidly changing reality, were our major achievements. x By contrast, our organization had been founded to correct the shortcomings of a movement that was already on the decline. A new kind of leadership would have to come out of a new movement whose hopes and dreams were still undefined.

****

In Detroit we did not have to wait long for the opportunity to begin creating a new movement. It came in 1988 when Coleman Young, Detroit’s first black mayor, began grasping at straws in his efforts to stop the violence that was escalating among black youth in the wake of de-industrialization.

Coleman Young was a tough and charismatic politician who had been a Tuskegee airman during World War II and a leader of the National Negro Labor Council and a state senator in the post-war years. He was elected Mayor in 1973 not only because the black community wanted a black mayor but because the massive rebellion in July 1967 had warned the power structure that a white mayor could no longer maintain law and order.

As the city’s new CEO, Young acted quickly to eliminate the most egregious examples of racism in the police and fire departments and at city hall. But he was helpless against the relentless de-industrializing of the city and the widespread violence resulting from the drug economy that jobless blacks had created in the inner city. By the mid-1980s the school system was in deep trouble because Detroit teenagers were asking themselves “Why stay in school hoping that some day you’ll get a good job when you can make a lot of money rollin’ right now?” In the summer of 1986 47 young Detroiters were killed and 365 wounded, among them sixteen-year-old Derick Barfield and fourteen-year-old Roger Barfield. Their mother, Clementine Barfield, responded by founding Save Our Sons and Daughters (SOSAD) which received widespread local and national attention. I edited the SOSAD newsletter and Jimmy contributed a column: “What can we be that our children can see?”

For three years from 1989 to 1992, through the heat of summer and the sleet of winter, we participated in the weekly anti-crackhouse marches of WE PROS (We the People Reclaim Our Streets), chanting “Up with hope, Down with dope!“ “Drug Dealers, Drug Dealers, you better run and hide, ‘cause people are uniting on the other side!” In a few neighborhoods, especially Dorothy Garner’s near the Linwood exit of the Lodge Freeway, we were successful in reducing crime and violence. But our marches did not attract young people, and we recognized that any program to rebuild and respirit Detroit had to be built around a youth core.

Meanwhile, Young had been trying in vain to keep or bring manufacturing plants in the city. xi Near the end of his fourth term, in 1988, he decided that casino gambling was the solution. Gaming, he said, was an industry that would create fifty thousand jobs. To defeat Young’s proposal, we joined Detroiters Uniting, a coalition of community groups, blue collar, white collar and cultural workers, clergy, political leaders and professionals, led by two preachers, United Methodist pastor William Quick and Baptist pastor Eddie Cobbin, one white and one black. I was the vice-president. Our concern,” we said, “is with how our city has been disintegrating socially, economically, politically, morally and ethically…. We are convinced that we cannot depend upon one industry or one large corporation to provide us with jobs. It is now up to us – the citizens of Detroit – to put our hearts, our imaginations, our minds, and our hands together to create a vision and project concrete programs for developing the kinds of local enterprises that will provide meaningful jobs and income for all citizens.”

During the struggle Young denounced us as “naysayers.” “What is your alternative?” he demanded. Responding to Young’s challenge, Jimmy made a speech in which he projected an alternative to casino gambling: the vision of a new kind of city whose foundation would be people living in communities and citizens who take responsibility for decisions about their city instead of leaving these to politicians or to the marketplace, and who also create small enterprises that emphasize the preservation of skills and produce goods and services for the local community. xii

To introduce this vision, in November 1991 we organized a Peoples Festival of community organizations, describing it as “A multigenerational, multicultural celebration of Detroiters, putting our hearts, minds, hands and imagination together to redefine and recreate a city of Community, Compassion, Cooperation, Participation and Enterprise in harmony with the Earth.”

A few months later, harking back to Mississippi Freedom Summer and drawing on our connections in the city and with nationally emerging environmental groups, we founded Detroit Summer, with a long list of endorsers, as a “Multicultural, Intergenerational Youth Program/Movement to Rebuild, Redefine and Respirit Detroit from the ground up.“ Detroit Summer youth volunteers began working on community gardens with African American southern-born elders (they called themselves Gardening Angels) who were already appropriating vacant lots to plant these gardens, not only to produce healthier food for themselves and their neighbors, but to instill respect for nature and a sense of process in city youth. Detroit Summer youth also rehabbed houses, painted public murals in the community, cleaned up neighborhood parks, and engaged in both intergenerational and youth-only dialogues.

There was something magical about Detroit Summer as there had been about Mississippi Freedom Summer. In a city that had once been the national and international example of the miracles of the industrial epoch but had now become a sea of vacant lots and abandoned houses, people were moved by the sight of young people and elders reconnecting with one another and with the earth. Their community gardens created a new image of vacant lots, not as blight but as a treasure-house of health-giving food. Their murals established a positive youth presence in the community. Students from universities all over the country who participated in or heard of Detroit Summer began to see their own futures, the future of cities and the environmental movement in a new light.

The result since 1992 has been an escalating urban agricultural movement in Detroit: neighborhood gardens, youth gardens, church gardens, school gardens, hospital gardens, senior independence gardens, teaching gardens, wellness gardens, Hope Takes Root gardens, Kwanzaa gardens.

A few blocks from the Boggs Center, Capuchin monks have created Earthworks, a program which uses gardening to educate Detroit school children in the science, nutrition and biodiversity of organic agriculture and also provides fresh produce for WIC and the Capuchin Soup Kitchen’s daily meals.

At the Catherine Ferguson Academy, a public high school for pregnant teens and teenage mothers, students raise vegetables and fruit trees. They also built a barn to house a horse, donkey, and small animals that provide eggs, meat, milk and cheese for the school community. xiii

Architectural students at University of Detroit Mercy produced a documentary called Adamah (“of the earth” in Hebrew), envisioning how a two and one-half acre square mile area not far from downtown Detroit could be developed into a self-reliant community with a vegetable farm to produce food, a tree farm and sawmill to produce lumber, schools that include community-building as part of the curriculum, and co-housing as well as individual housing. xiv

The National Black Farmers Union, whose mantra is “We can’t free ourselves until we feed ourselves,” brought its annual convention to Detroit.

Inspired by Jimmy’s speech, Jackie Victor and Ann Perrault worked in a bakery to learn the trade and then opened their own organic bakery in midtown Detroit as an example of the kind of small business that our cities need instead of big box and chain stores. xv

Every August the Detroit Agricultural Network conducts a tour of community gardens. In 2007 six big buses were not enough for the hundreds of people of all ethnic groups attracted by Detroit’s mushrooming urban agricultural movement. After the tour, a retired city planner told me that it gave her a sense of how important community gardens are to a city. “They reduce neighborhood blight, build self-esteem among young people, provide them with structured activities from which they can see results, build leadership skills, provide healthy food and a community base for economic development. I see it as the ‘Quiet Revolution.’ It is a revolution for self-determination taking place quietly in Detroit.” xvi

This quiet revolution has been preparing Detroiters to meet today’s growing crises of global warming and spiraling food prices. Instead of paying prices we can’t afford for produce grown on factory farms and imported from Florida and California in gas-guzzling, carbon monoxide-releasing trucks, we can grow our own food and not only achieve food security but grow our souls because we are creating a new balance between necessity and freedom. xvii

This revolution was also deepening our sense of the connections between our own locally based work and the new urban agriculture movement weaving a new future both in our own country and around the earth. From our growing conviction that something new was emerging, we began to look again at larger philosophical questions.

****

During the 1960s Jimmy and I had paid little attention to the speeches and writings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Like other members of the Detroit black community, made up largely of former Alabamians, we rejoiced at the victories the civil rights movement was winning in the south. xviii But as activists struggling for black power in Detroit, we identified much more with Malcolm X than with Martin. In fact, we tended to view King’s call for nonviolence and for the beloved community as somewhat naíve and sentimental.

Jimmy and I were also not involved in the fifteen-year campaign that Detroit Congressman John Conyers Jr. launched in 1968 to declare King’s birthday on January 15 a national holiday. I recall holding back because I was concerned that a King holiday would obscure the role of grassroots activists and reinforce the tendency to rely on charismatic leaders.

Meanwhile I was troubled by the way that black militants kept quoting Malcolm’s “by all means necessary,” ignoring the profound changes that Malcolm was undergoing in the year following his split with the Nation of Islam. After his pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm was seriously rethinking black nationalism, and in December 1964 he had gone to Selma, Alabama, to explore working with Martin Luther King Jr. xix

As violence in Detroit and other cities escalated in the wake of the urban rebellions, I began to wonder whether events might have taken a different course if we had found a way to blend Malcolm’s militancy with King’s nonviolence and vision of the beloved community.

During this period my interest in King was also piqued by the little pamphlet A Way of Faith, A Time for Courage published in 1984 by the Seattle NOAR local. In this pamphlet our old friends, Vincent and Rosemary Harding, who had worked closely with MLK in the 1960s, explain that “Martin wasn’t assassinated for simply wanting black and white children to hold hands, but because he said that there must be fundamental changes in this country and that black people must take the lead in bringing them…. Put simply, these problems are Racism, Materialism, Militarism, and Anti-Communism.” xx

Meanwhile, in 1982, Reagan signed into law the decision to observe King’s birthday as a national holiday, and scholars were beginning to re-evaluate his work and life. xxi In 1992, at the opening ceremony of Detroit Summer, I had noted the similarity between our vision and King’s projections for direct youth action “in our dying cities.” In the spring of 1998, when I was asked what I thought about the Black Radical Congress, I replied that in order to create a new movement, we must first understand the old. For radicals in this period this means grappling with the significance of the Black Panther Party, Malcolm X and King. xxii

As a result of all these developments, I began studying King’s life and work from the perspective of RETC and our work in Detroit. To my delight I discovered that Hegel had been King’s favorite philosopher. This reminded me of the influence that Hegel has had on my own life ever since I read his Phenomenology in my early twenties and learned that the process of constantly overcoming contradictions, or what Hegel called the “suffering, the patience, and the labour of the negative,” is the key to the continuing evolution of humanity. xxiii

I also discovered that in the last three years of his life King had viewed the American preoccupation with rapid economic advancement as the source of our deepening crises both at home and in our relationships with the rest of the world.

As King’s life and ideas became more meaningful to me, I began speaking about him at MLK holiday celebrations and on other occasions. For example, at the University of Michigan 2003 MLK Symposium, my speech was entitled “We must be the change.” At Union Theological Seminary in September 2006, I spoke on “Catching Up with Martin.” At Eastern Michigan University in January 2007, I emphasized the need to “Recapture MLK’s Radical Revolutionary Spirit/Create Cities and Communities Of Hope.” At the Brecht Forum in May 2007, my speech was entitled “Let’s talk about Malcolm and Martin.” xxiv

The more I talked about King, the more I felt the need for each of us to grow our own souls in order to overcome the new and more challenging contradictions of constantly changing realities.

The 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott, I realized, was the first struggle by an oppressed people in western society based on the concept of two-sided transformation, both of ourselves and of our institutions. Inspired by the twenty-six-year-old King, a people who had been treated as less than human had struggled for more than a year against their dehumanization, not as angry protesters or as workers in the plant, but as members of the Montgomery community, new men and women representing a more human society in evolution. Using methods including creating their own system of transportation that transformed themselves and increased the good rather than the evil in the world, exercising their spiritual power and always bearing in mind that their goal was not only desegregating buses but building the beloved community, they had inspired the human identity, anti-war and ecological movements that during the last decade of the twentieth century were giving birth to a new civil society in the United States.

The more I studied King’s life and ideas, especially in the last three years before his assassination, the more I recognized the similarity between our struggles in Detroit after the 1967 rebellion and King’s after the 1965 Watts uprising.

On August 6, 1965, nearly a decade after the Montgomery Bus Boycott, King was among the black and white leaders who joined President Johnson in celebrating the signing of the Voting Rights Act, the result of the march from Selma to Montgomery.

Less than a week later, on August 11, black youth in Watts, California, protesting the police killing of a speeding driver, exploded in an uprising in which thirty-five people died and thousands were arrested. When King flew to Watts on August 15, he discovered to his surprise that few black youth in Watts had even heard of him or his strategy of non-violence and that, despite the loss of lives, they were claiming victory because their violence had forced the authorities to acknowledge their existence.

The Watts uprising forced King to recognize how little attention he himself had paid to black youth in the cities. So in early 1966 he rented an apartment in the Chicago ghetto and was able to get a sense of how the anger that exploded in Watts was rooted in the powerlessness and uselessness that is the daily experience of black youth made expendable by technology. He also discovered the futility of trying to involve these dispossessed young people in the kinds of nonviolent mass marches that had worked in the South. And they gave him a lot to think about when they demanded to know why they should be nonviolent in Chicago when the U.S. government was employing such massive violence against poor peasants in Vietnam.

Thus, King’s “A Time to Break Silence” speech against the war in Vietnam was the result of his wrestling not only with the Vietnam War but with the questions raised by these young people in what he called “our dying cities.”

“The war in Vietnam,” he recognized, ”is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit. We are on the wrong side of a world revolution because we refuse to give up the privileges and the pleasures that come from the immense profits of overseas investment.

“We have come to value things more than people. Our technological development has outrun our spiritual development. We have lost our sense of community, of interconnection and participation.”

In order to regain our humanity, he said, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values against the giant triplets of racism, materialism and militarism. Projecting a new vision of global citizenship, he called on every nation to “develop an over-riding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies.” xxv

By drawing on the transformational ideas of Hegel, Gandhi and Jesus Christ, all of which had become more meaningful to him since the Montgomery Bus Boycott, King began to connect the despair and violence in the urban ghettos with the alienation which young people experience in today’s world.

This generation is engaged in a cold war with the earlier generation. It is not the familiar and normal hostility of the young groping for independence. It has a new quality of bitter antagonism and confused anger which suggests basic values are being contested.

The source of this alienation is that our society has made material growth and technological advance an end in itself, robbing people of participation, so human beings become smaller while their works become bigger. xxvi

The way to overcome this alienation, King said, is by changing our priorities. Instead of pursuing economic productivity, we need to expand our uniquely human powers, especially our capacity for agape, which is the love that is ready to go to any length to restore community.

This love, King insisted, is not some sentimental weakness but somehow the key to ultimate reality. xxvii

In practice, taking this statement seriously requires a radical change or paradigm shift in our approach to organizing and to citizenship, which is the practice of politics. Instead of pursuing rapid economic development and hoping that it will eventually create community, we can only create community if we do the opposite, i.e., begin with the needs of the community and with creating loving relationships with one another and with the earth.

It also requires a paradigm shift in how we address the three main questions of philosophy: What does it mean to be a human being? How do we know? How shall we live? It means rejecting the scientific rationalism (based on the Cartesian body-mind dichotomy), which recognizes as real only that which can be measured and therefore excludes the knowledge which comes from the heart or from the relationships between people. It means that we must be willing to see with our hearts and not only with our eyes. xxviii

King believed that we could achieve the beloved community because he saw with his heart and not only with his eyes. We can learn the practical meaning of love, he said, “from the young people who joined the civil rights movement, putting on overalls to work in the isolated rural South because they felt the need for more direct ways of learning that would strengthen both society and themselves.”

What we need now in our dying cities, he said, are ways to provide young people with similar opportunities to engage in self-transforming and structure-transforming direct action. xxix

King was assassinated before he could begin to develop strategies to implement this revolutionary/evolutionary perspective for our young people, our cities, and our country. After his death his closest associates were too busy taking advantage of the new opportunities for advancement within the system to keep his vision and his praxis alive.

****

Meanwhile, as we continued our struggle to rebuild, redefine and respirit Detroit from the ground up, I was keeping up with the new thinking taking place on a scale unparalleled since the Enlightenment which preceded the French revolution more then two hundred years ago. xxx

I was also very conscious of the new revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces that had been emerging since King’s assassination.

In the wake of the civil rights, black power and anti-war movements of the 1960s, women, Chicanos, Native Americans, Asian Americans, gays, lesbians, and the disabled were creating their own movements for recognition and social change. The vitality and creativity of these movements reminds us that our country has not been and never will be just black and white.

Out of their experiences of sexism in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements, women were carrying on a many-sided philosophical and practical struggle against all forms of patriarchy. Activist intellectuals like Starhawk were exposing the sixteenth and seventeenth century witch hunts as the means by which the British power structure expropriated the land of the villagers and replaced the immanent knowledge of women with the scientific rationalism of the intellectual elite. Indian physicist and activist Vandana Shiva and German sociologist Maria Mies were explaining how the labor of western societies “colonizes” women, nature and the Third World. By a deeper appreciation of the work of women, peasants and artists, they suggested, we can get an idea of what work will be like in a new non-capitalist society: difficult and time-consuming but rewarding and joyful because it nurtures life. xxxi

Also, having discovered that the personal is political, women activists were abandoning the charismatic male, vertical, and vanguard party leadership patterns of the 1960s and creating more participatory, more empowering, more horizontal kinds of leadership. Instead of modeling their organizing on the lives of men outside the home, e.g. in the plant or in the political arena, they were beginning to model it on the love, caring, healing and patience which are an organic part of the everyday lives of women. These, along with an appreciation of diversity and of strengths and weaknesses, go into the raising of a family. xxxii

Transnational corporations were growing by leaps and bounds. By the 1980s factory jobs were declining as more and more capital was exported overseas to countries where more profit could be made with cheaper labor. National and local legislation establishing minimum social and environmental standards were being overruled by organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO). Global corporations were reducing the power of nation-states, turning people all over the world into consumers, and changing the relationships between people and with the earth into commodity relationships.

In response to this commodification and dehumanization, tens of thousands of individuals and groups, representing very diverse sections of society, including steelworkers and anarchists, mobilized to close down the WTO meeting in Seattle in November 1999. During the ”Battle of Seattle” Starhawk and other activists created affinity groups to decide their own tactics democratically. At subsequent mobilizations, e.g. against Free Trade Areas of the Americas (FTAA) in Quebec and Miami, these affinity groups also set up their own communal kitchens, street medic teams, and media centers. Out of these experiences local activists began to see the possibilities for new forms of year-round, more democratic kinds of organizing in their communities.

Following mass mobilizations against corporate globalization in Seattle, Quebec, and Miami, thousands of individuals and groups from around the world gathered at annual World Social Forums and National Social Forums to declare that “Another World is Possible.”

In response to corporate globalization, people in communities all over the world began to create new ways of living at the local level to reconnect themselves with the earth and with one another. xxxiii

The best known of these are the Zapatistas, the indigenous peoples of Chiapas who took over Mexican cities on January 1, 1994, the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) legalized the power of transnational corporations over local economies and government. The goal of the Zapatistas is to create a participatory economy and a participatory democracy from the ground up by a patient process of democratic discussions and nonviolence. Since 1994 Chiapas has become the Mecca and model for revolutionaries all over the world. xxxiv

In the last four years, as a member of the Beloved Communities Initiative, I have been impressed with the diversity of the groups which are in the process of creating new kinds of communities in the United States. xxxv

These include Detroit-City of Hope; the Beloved Community Center and Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Greensboro, North Carolina; an annual fall gathering in New Mexico where Tewawa women share the wisdom of indigenous cultures with people of many different backgrounds; Growing Power in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a two and one-half acre farm with five greenhouses which is not only growing food for two thousand families but new multiethnic community relations; Access, a Center for Independent Living in Chicago, where the prideful struggle of individuals with disabilities is deepening our understanding of what it means to be a human being; Cookman United Methodist Church in North Philadelphia, where neighborhood residents are creating a loving, caring environment for young people to complete their schooling and also develop leadership skills; Great Leap in Los Angeles, where individuals from different faith backgrounds are expanding their individual identities through spiritual and physical rituals and exercises.

Since 1968 a counterrevolutionary movement has also been developing in the United States. It began with the election of Richard Nixon as president in reaction to the turmoil of the 1960s, e.g. the urban uprisings, the assassinations of MLK and Robert Kennedy, the police riot at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. In the 1980s, as the export of jobs created unemployment and insecurity among factory workers and with families also in disarray, a growing number of Americans began to blame the anti-Vietnam war movements and blacks, feminists, gays, liberals and radicals for turning the American Dream into a nightmare. xxxvi

Around the same time a group of conservatives in the power structure with close ties to the arms and energy industries, including Dick Cheney, who was President Gerald Ford’s chief of staff in the 1970s, and Donald Rumsfeld, who was Ford’s secretary of defense, began developing a long-range program to restore U.S. hegemony. Their aim was to increase an already enormous military budget at the expense of domestic social programs, topple regimes resistant to U.S. corporate interests, and replace the UN’s role of preserving and extending international order with U.S. military bases. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these neoconservatives felt that the main obstacle to unilateral U.S. actions had been removed, and in 1997 they founded the Project for the New American Century. xxxvii

The attacks of September 11, 2001, gave them the opportunity to launch the war in Afghanistan in 2001 and the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

How do we overcome this shameful and shameless counterrevolution which has cost the lives of so many American servicemen and women in Iraq and Afghanistan, killed more than a million Iraqis, made refugees of other millions, used security as an excuse to destroy rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, and violated international law and dishonored our country by torturing detainees at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo? Because it is a movement, it cannot be defeated in the ordinary course of electoral politics. For the same reason, it cannot be eliminated by a seizure of power or insurrection like the Russian revolution in 1917. xxxviii It can only be overcome by a new kind of evolutionary humanist revolution.

In a speech entitled “The Next American Revolution,” which I gave on March 16, 2008, at the closing plenary of the Left Forum in New York City, I explained how this revolution would differ from all previous revolutions. xxxix

I began by quoting from the chapter on “Dialectics and Revolution” in RETC, where, nearly 30 years before 9/11, Jimmy wrote:

“The revolution to be made in the United States will be the first revolution in history to require the masses to make material sacrifices rather than to acquire more material things. We must give up many of the things which this country has enjoyed at the expense of damning over one-third of the world into a state of underdevelopment, ignorance, disease and early death. Until the revolutionary forces come to power here, this country will not be safe for the world and revolutionary warfare on an international scale against the United States will remain the wave of the present – unless all of humanity goes up in one big puff.”

It is obviously going to take a tremendous transformation to prepare the people of the United States for these new social goals. But potential revolutionaries can only become true revolutionaries if they take the side of those who believe that humanity can be transformed.

Thus the American revolution at this stage in our history, and in the evolution of technology and of the human race, is not about jobs or universal health insurance or fighting inequality or making it possible for more people to realize the American Dream of upward mobility. It is about creating a new American Dream whose goal is a higher humanity instead of the higher standard of living that is dependent upon empire. It is about acknowledging that we Americans have enjoyed upward mobility and middle class comforts and conveniences at the expense of other peoples all over the world. It is about living the kind of lives that will end the galloping inequality both inside this country and between the global North and South, and also slow down global warming. About practicing a new, more active, global and participatory concept of citizenship. About becoming the change we want to see in the world.

This means that it is not enough to organize mobilizations that call on Congress and the President to end the war in Iraq. We must also challenge the American people to examine why 9/11 happened and why so many people around the world who, although they do not support the terrorists, understand that terrorism feeds on the anger that millions feel about U.S. support of the Israel occupation of Palestine and Middle East dictatorships, and the way that we treat whole countries, the peoples of the world, and nature only as resources enabling us to maintain our middle class way of life.

We have to help the American people find the moral strength to recognize that, although no amount of money can compensate for the countless deaths and indescribable suffering that our criminal invasion and occupation have caused the Iraqi people, we have a responsibility to make the material sacrifices that will enable them to begin rebuilding their infrastructure. We have to help the American people grow our souls enough to recognize that, since we have been consuming 25 percent of the planet’s resources even though we are only 4 percent of the world’s population, we are the ones who must take the first big steps to reduce greenhouse emissions. We are the ones who must begin to live more simply so that others can simply live.

Thus, the next American revolution is about challenging the American people and ourselves to “form a more perfect union” by carrying on the revolutionary legacy of William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, Sojourner Truth, Rosa Parks, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Audre Lorde, and Malcolm and Martin. It is about claiming this legacy openly and proudly, reminding ourselves and every American that our country was born in revolution. Therefore we are the real Americans while the un-Americans are the neocons, the homophobes, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, and the anti-immigrant crusaders who, like yesterday’s slaveowners, General Custers, imperialists, and White Citizens Councils, are subverting what is best in the American tradition.

The courage, commitment, conviction and visionary strategies required for this kind revolution are very different from those required to storm the Kremlin or the White House. We can no longer view the American people as masses or warm bodies to be mobilized in increasingly aggressive and more massive struggles for higher wages, better jobs, or guaranteed health care. Instead we must challenge them and ourselves to engage in activities at the grassroots level that build a new and better world by improving the physical, psychological, political and spiritual health of ourselves, our families, our communities, our cities, and our planet.

To my surprise and delight the two thousand or more people gathered in the Great Hall of Cooper Union responded to my speech with a standing ovation. It was, I believe, a sign that a new generation of Americans is ready to recognize that the next American revolution is not about reconstituting the welfare state but about making the radical revolution in values that Martin Luther King Jr. advocated. From the calamity of the Vietnam and Iraq wars they have learned that power does not come out of the barrel of a gun or from taking over the White House. Only right makes might. xi

I also believe that, in much the same way and for many of the same reasons that Detroiters have been forced by the devastation of de-industrialization to begin rebuilding, redefining and respiriting our city from the ground up, the American people are being forced by the interconnected crises of the Iraq war, global warming, floods, job insecurity, and a sinking economy to begin making a radical revolution in their way of life.

For example, a lot of Americans are furious these days because gas prices are soaring. But one hundred years from now our posterity may bless this period when high gas prices finally forced Americans to bike or take public transportation to work, to dream of neighborhood stores within walking distance, and to start building cities that are friendlier to children and pedestrians than to cars. xli

Likewise, as food prices skyrocket, hunger riots erupt, and obesity, diabetes, and other health problems caused by our industrialized food production system reach epidemic levels, the urban agricultural movement is the fastest growing movement in the United States. Americans are beginning to recognize that our health and the health of our communities and our planet require that we grow our own food closer to where we live.

This is how necessity and freedom have come together in Detroit, and how I see them coming together in other cities in the days ahead. It was not an abstract idealism but the real and deteriorating conditions of life in a de- industrialized Detroit that moved us to found Detroit Summer in 1992, so that young people could begin taking responsibility for rebuilding, redefining and respiriting our city from the ground up.

****

2007 was the fortieth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Break the Silence” speech and also of the July 1967 Detroit rebellion. To commemorate these historic events, the Boggs Center convened two meetings: one in April “To Transform Grief into Hope” and one in July to involve Detroiters in a conversation on “Where Do We Go from Here?”

At the July meeting people told so many inspiring stories of grassroots activities and projects that Detroiters are creating or want to create that we decided to launch a Detroit-City of Hope campaign to identify, encourage and promote these as a new infrastructure for our city. Among these activities and projects (which recall those in the Manifesto for an American Revolutionary Party in 1982 and in “Rebuilding Detroit: An Alternative to Casino Gambling” in 1988) are:

- expanding urban agriculture and small businesses to create a sustainable local economy.

- re-inventing work so that it is not just a job done for a paycheck but to develop people and build community.

- re-inventing education to include children in activities that transform both themselves and their environment.

- creating co-ops to produce local goods for local needs.

- developing peace zones to transform our relationships with one another in our homes and on our streets.

- replacing punitive justice with restorative justice programs to keep nonviolent offenders in our communities and out of prisons that not only misspend billions much needed for roads and schools but turn minor offenders into hardened criminals. xlii Over thirty years ago in RETC we projected a vision of two-sided transformation of ourselves and our institutions as the key to the next American revolution. In the last three years of his life, in response to the Vietnam war and youth despair in our dying cities, this is the kind of American revolution that MLK was also projecting in his call for a radical revolution of values.I believe that twenty-first century revolutions will be huge steps forward in the continuing evolution of the human race. But I also believe that, more often than not, these huge steps will be the accumulation and culmination of small steps, like planting community gardens and creating community peace zones. xliiiWe are all works in progress, always in the process of being and becoming. Periodically there come times like the present when the crisis is so profound and the contradictions so interconnected that if we are willing to see with our hearts and not only with our eyes, we can accelerate the continuing evolution of the human race towards becoming more socially responsible, more self-conscious, more self-critical human beings.

Our country is also a work in progress. This is our time to reject the old American Dream of a higher standard of living based upon empire, and embrace a new American Dream of a higher standard of humanity that preserves the best in our revolutionary legacy. We can become the leaders we are looking for.

Towards that end we need to keep combining practice with reflection and urgency with patience. That is what I have learned after nearly seven decades of struggle for radical social change.

———————— FOOTNOTES —————————-

i After Jimmy’s death, friends and comrades founded the James and Grace Lee Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership to continue our legacy of combining practice with reflection, and local groundedness with visionary strategizing. Some of Jimmy’s most memorable speeches (Think Dialectically, Not Biologically; The Next Development in Education; Rebuilding Detroit: An Alternative to Casino Gambling) are posted on the Center’s website at http://www.boggscenter.org

The naturalness and ease with which Jimmy thought dialectically never ceased to amaze me. It was rooted in his sense of himself as a black American, born and raised in the deep agricultural South, who then became a Chrysler worker for twenty-eight years, and was now wondering about the far-reaching cultural changes that the new informational technology was bringing.

Almost everyone who talked with him for only a few minutes realized that they had come into contact with an “organic intellectual,” even if they had never heard of Gramsci. It was obvious that Jimmy’s ideas came not out of books but out of continuing reflection on his own life and the lives of working people like himself.

Long before we met, he had decided that he was an American revolutionist who loved this country enough to change it. He was very conscious that the blood and sweat of his ancestors was in this country’s soil and had already embarked on the struggle to ensure that his people would be among those deciding its economic and political future. That is why he was able to write paragraphs like the following that end chapter 6 on “Dialectics and Revolution” in RETC:

Technological man/woman developed because human beings had to discover how to keep warm, how to make fire, how to grow food, how to build dams, how to dig wells. Therefore human beings were compelled to manifest their humanity in their technological capacity, to discover the power within them to invent tools and technologies which would extend their material powers. We have concentrated our powers on making things to the point that we have intensified our greed for more things and lost the understanding of why this productivity was originally pursued. The result is that the mind of man/woman is now totally out of balance, totally out of proportion.

That is what production for the sake of production has done to modern man/woman. That is the basic contradiction confronting everyone who has lived and developed inside the United States. That is the contradiction which neither the U.S. government nor any social force in the United States up to now has been willing to face, because the underlying philosophy of this country, from top to bottom, remains the philosophy that economic development can and will resolve all political and social problems.

ii The four of us, from very different backgrounds, had been members of the Johnson-Forest Tendency led by West Indian Marxist C.L.R. James and Russian-born Marxist Raya Dunayevskaya. One Alabama-born African American, one New England Yankee, one Jewish American and one Chinese American, we reflected the American experience.

To learn more about Lyman and Freddy and these conversations, see Conversations in Maine: Exploring our Nation’s Future, South End Press, 1978; and my autobiography, Living for Change, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, pp. 146-157. Lyman died in 1978 and Freddy in 1999. Richard Feldman wrote the introduction to Conversations in Maine. Shea Howell has continued to host the conversations in Maine since Freddy’s death. Both Rich and Shea reviewed this introduction and made helpful suggestions.

iii Decades before writing Das Kapital in the British Museum, a twenty-nine-year-old Karl Marx had anticipated this contradiction when he wrote in the Communist Manifesto that as a result of the “constant revolutionizing of production… all that is sacred is profaned, all that is solid melts into air, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his conditions of life and his relations with his kind.”

iv Harry Braverman, whose classic Labor and Monopoly Capital was also published in 1974, represented Monthly Review Press in these arrangements. Monthly Review had already published two books by Jimmy, The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Worker’s Notebook, in 1963 (brought to the attention of Leo Huberman and Paul Sweezy by W.H. “Ping” Ferry); and Racism and the Class Struggle: Further Pages from a Black Worker’s Notebook, in 1970. In The American Revolution, Jimmy had challenged the validity of Marx’s nineteenthcentury analysis for a technologically-advanced society like the United States in the midtwentieth century, and had also warned that to make a revolution in our country, all Americans, including workers, blacks, and the most oppressed, would have to make political and ethical choices. Soon after its publication, The American Revolution was translated and published in five other languages (Japanese, French, Italian, Portuguese and Catalan. Racism and the Class Struggle, a compilation of Jimmy’s speeches during the 1970s, has been widely read in Black Studies classes. At a twentieth anniversary celebration of The American Revolution in 1983, Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis linked RETC to Jimmy’s earlier books by performing a LOVER-LOVE/REVOL-EVOL skit.

v For example, before the 1967 rebellion, there were only a few black foremen in the auto industry and few, if any, black tellers in Detroit banks or black managers in supermarkets. In 1965 we tried, unsuccessfully, to get a few blacks elected to the Detroit City Council by organizing a plunking (“four and no more”) campaign. In 1966 Detroit high school students went on strike to demand Black History classes and black principals. After the rebellion, the white power structure was so fearful of a recurrence that it rushed to promote blacks to highly visible positions.

vi Shea Howell used to joke that an elephant could be born in the time it took to complete one of our study groups. Living for Change, p. 163.

vii This decision was explained in the new introduction to the fifth printing of the Manifesto for a Black Revolutionary Party, published in April 1976.

viii Over the years it has been difficult for traditional radicals to develop a vision and praxis for an American revolution because any appreciation of the uniqueness of American history was shunned as “American exceptionalism.” As a result, historical agency was displaced onto subjects in other countries, especially in the Third World. Jimmy began thinking about his first book The American Revolution when he saw how radicals in the plant would fumble around for an answer when workers asked “What is socialism and why should the people struggle for it?” The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Workers Notebook, Monthly Review Press, 1963, p. 43. See the little 1976 pamphlet Towards a New Concept of Citizenship by James Boggs.

ix GM worker Jim Hocker, who co-authored But What About the Workers? with Jimmy in 1974, stopped by regularly after work for conversations in our kitchen. In 1982 NOAR published these conversations as These Are the Times that Try Our Souls: Conversations in Detroit, with an introduction by Rich Feldman who worked at the Ford truck plant.

x These publications can be ordered from the James & Grace Lee Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership at http://www.boggscenter.org.

xi In 1980 Coleman Young,

joined with General Motors to announce that the city was demolishing an entire neighborhood, bulldozing 1,500 houses, 144 businesses, sixteen churches, two schools, and a hospital in Poletown so that GM could build a Cadillac plant, with Detroit assuming the costs of land clearance and preparation. The endangered community, an integrated neighborhood of Poles and blacks, carried on a heroic struggle to save their homes and their community, but the UAW supported Young and GM because they promised that the new plant would employ six thousand workers. Ralph Nader sent in a team of five members to work with the Poletown protesters for six months. But in vain. All the homes, businesses, churches, schools, and the hospital were leveled. After the demolition I could not bear to drive around the site that was not far from our house. It was like a moonscape, so desolate that I could not tell east from west or north from south.

When the new Poletown plant finally opened in 1984, it was so automated that it only employed 2,500 workers, and it has never employed more than 4,000 – this despite the fact that the two older Cadillac plants that the Poletown plant replaced had employed 15,000 people as recently as 1979. Living for Change, p. 179.

xii James Boggs: “Rebuilding Detroit: an Alternative to Casino Gambling.” http://www.boggscenter.org. xiii “The Emerald City” by Michele Owens, Oprah Magazine, April 2008.

xiv See “Down a green path: An alternative vision for a section of east Detroit takes shape” by Curt Guyette, Metro Times, October 31, 2001.

xv “On a roll: Avalon International Breads isn’t just about making dough” by Lisa M. Collins, Metro Times, October 4, 2002.

xvi “Detroiters point way for twenty-first century cities” by Grace Lee Boggs, Michigan Citizen, November 25- December 1, 2007. Eight years ago I began writing weekly columns in the Michigan Citizen. The hundreds of columns I have written are posted on the Boggs Center website at http://www.boggscenter.org.

xvii “… it is unfair, or at least deeply ironic, that black people in Detroit are being forced to undertake an experiment in utopian post-urbanism that appears to be uncomfortably similar to the sharecropping past their parents and grandparents sought to escape. There is no moral reason why they should do and be better than the rest of us – but there is a practical one. They have to. Detroit is where change is most urgent and therefore most viable. The rest of us will get there later, when necessity drives us too, and by that time Detroit may be the shining example we can look to, the post-industrial green city that was once the steel-gray capital of Fordist manufacturing.” Rebecca Solnit: “Detroit Arcadia: Exploring the post-American landscape.” Harper’s Magazine, July 2007.

xviii In June 1963, Dr. King, arm-in-arm with Detroit black power leaders and labor leader Walter Reuther, led a huge march down Woodward Avenue in Detroit. I was one of the organizers of the march. For the story of how and why it came about, see Living for Change, p. 124.

xix In the spring of 1964, together with Max Stanford of Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM); Baltimore Afro-American reporter William Worthy, and Patricia Robinson of Third World Press, Jimmy and I met with Malcolm in a Harlem luncheonette to discuss our proposal that he come to Detroit to help build the Organization for Black Power. Malcolm’s response was that we should go ahead while he served the movement as an “evangelist.” However, after Malcolm discovered during his pilgrimage to Mecca that revolutionaries come in all races, he realized that he had to go back to square one to do the hard theoretical work necessary to develop a new body of ideas. As he told Jan Carew in a conversation in London:

I’m a Muslim and a revolutionary, and I’m learning more and more about political theories as the months go by. The only Marxist group in America that offered me a platform was the Socialist Workers Party. I respect them and they respect me. The Communists have nixed me, gone out of the way to attack me, that is, with the exception of the Cuban Communists. If a mixture of nationalism and Marxism makes the Cubans fight the way they do and make the Vietnamese stand up so resolutely to the might of America and its European and other lapdogs, then there must be something to it. But my Organization of African American Unity is based in Harlem and we’ve got to creep before we walk and walk before we run…. But the chances are that they will get me the way they got Lumumba before he reached the running stage.

— Jan Carew Ghosts in our Blood: With Malcolm X in Africa, England, and the Caribbean, p. 36. Lawrence Hill Books 1994.

This kind of introspection, questioning and transformation, which were so characteristic of Malcolm, has been mostly ignored by black nationalists and Black Power militants.

xx Vincent wrote the first draft of MLK’s April 4, 1967 historic anti-Vietnam war speech, “Time to Break the Silence.” Years later, the ideas in the 1984 pamphlet were expanded and published by him in Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero: Orbis, 1996; revised 2007.

xxi For example, We Shall Overcome: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Freedom Movement, ed. Peter J. Albert and Ronald Hoffman, DaCapo Press, 1993, is a compilation of papers presented by an impressive group of scholars and activists at an October 1986 symposium convened in Washington, D.C. to reflect on King’s life and work following the decision to make King’s birthday an annual holiday.

xxii See my “Thoughts on the Black Radical Congress,” Michigan Citizen, May 10-16, 1998. Bob Lucas, to whom my letter is addressed, led the 1966 march into Cicero, Illinois.

xxiii The Phenomenology of Mind by G.W.F. Hegel, translated with an Introduction and Notes by J. B. Baillie, p.81. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1931.

xxiv See http://www.boggscenter.org for these and other speeches by me.

xxv “A Time to Break Silence,” reprinted in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. ed. James M. Washington, p. 231. Harper Collins, 1991.

xxvi The Trumpet of Conscience, reprinted in A Testament of Hope, ibid. p. 641.

xxvii King’s concept of love recalls Che Guevara’s: “Let me say, with the risk of appearing ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by strong feelings of love.” Exploring King’s concept can help us understand why Che’s statement has been so puzzling to traditional radicals and why Che lives on in the hearts of young revolutionaries.

For example, in a thought-provoking article, “King, the Constitution and the Courts,” theologians and lawyers Barbara A. Holmes and Susan Winfield Holmes challenge us to think more expansively about King’s concept of love. King’s, agape love is a foundational principle for social change…. For King, love is synonymous with ethics. It is a moral principle that provides context, norms, rules of engagement, and a vision of moral flourishing…. The strength of King’s belief in the law, his abiding faith in love as praxis, and the force of his performative acts forged crosscultural alliances and inspired even the courts to interpret the laws in a manner that for a time changed the face of the nation,,,,

King’s higher-law values also challenge the theory articulated by W.E.B. DuBois that double consciousness separated the public and private lives of black people…. One cannot claim to be operating with higher-law values unless a constant self-critique is part of the process…. King knew that love crucified, but not broken, was the only model that could redeem the dignity of those who sought freedom and those who conspired to deny it….